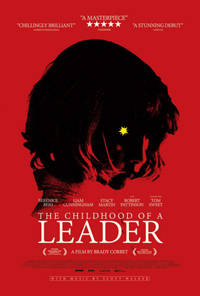

The Children Are Watching Us: Corbet’s Chilling Directorial Debut Contemplates Familial Fascism

Potent psychological complexity often feels compromised in favor of establishing easy to understand narrative developments in modern cinema, erasing subtexts in honor of direct emphasis to streamline audience interpretation. Not so with the impressive, calculating directorial debut of actor Brady Corbet, whose compelling The Childhood of a Leader bears striking resemblance to several of the auteurs the performer has pointedly aligned himself with through a wide-ranging filmography.

Potent psychological complexity often feels compromised in favor of establishing easy to understand narrative developments in modern cinema, erasing subtexts in honor of direct emphasis to streamline audience interpretation. Not so with the impressive, calculating directorial debut of actor Brady Corbet, whose compelling The Childhood of a Leader bears striking resemblance to several of the auteurs the performer has pointedly aligned himself with through a wide-ranging filmography.

Based loosely on a 1939 short story from Jean-Paul Sartre (with which it shares its title) and a 1965 novel, The Magus by John Fowles, the adaptation was co-written by the director’s partner Mona Fastvold (the two concocted the 2013 film The Sleepwalker in opposite functions), this 1918 set bildungsroman, divided into three chapters marked by significant tantrums of its main subject, hemorrhages Freudian menace from its first frames. A tale of historical unease, which provides an intimate glance at the psychological rearing of a child during WWI who would grow into an infamous Fascist leader (but not meant to be one of the obvious figureheads of the era), this is a fascinating, eerie portrayal of a crumbling oligarchy shedding its skin for the rise of a new terror.

In 1918 France, the Assistant Secretary (Liam Cunningham) to the US Secretary of State negotiates on behalf of President Wilson (for what will eventually result in the Treaty of Versailles). His wife (Berenice Bejo) is a German born woman who speaks fluent French, which has helped ease their family’s acclimation in their new locale. But their preadolescent son Prescott (Tom Sweet) seems to be having a tough time adjusting, and we greet him as he flings rocks at parishioners as they leave the church where he just performed as a choirboy. Chased through the woods, Prescott is caught and lightly censured by mum, who shuffles him off to bed while their father entertains family friend Charles Marker (Robert Pattinson) over billiards. As she attempts to lead little Prescott through the trials of the apology process, this soon becomes an ordeal, and leads to an ever widening breakdown between the child and his parents as growing political shadows darken their doorstep.

At the center of this psychological allegory of a monster is a familiar tale of domestic unrest, petite bourgeois travails marking a politically prominent family of hybrid international backgrounds. The notion of child rearing, or the lack thereof, bears the brunt of blame here, a particular petri dish of discontent. The aloof mother played by Berenice Bejo, (in one of the actresses’ strongest turns to date, even if it’s arguably one-note) seems the usual matriarchal harbinger of the sociopath, recalling the phantom of Mrs. Bates to the coldness of Tilda Swinton in We Need to Talk About Kevin, another mother who desperately wishes to ignore her growing distaste for her own progeny. Two other key relationships with young Prescott (an almost preternatural Tom Sweet as the cherubic hellion) solidifies the groundwork for his rebellion, including a French tutor played by a chaste Stacy Martin (a far cry from her Nymphomaniac performance) and Yolande Moreau’s affable maid, who coddles the boy. These servants, or minions to the family’s needs, also brings to mind Damien from Richard Donner’s classic horror film The Omen, the rearing of the Antichrist within the bosom of the affluent, politically minded nest of privilege. In an exchange with his tutor, Prescott mentions his mother refers to him as a ‘son of the world,’ a way to placate their status as outsiders within the confines of an older, dominant culture. Sweet is, almost by default, the only cast member to flex a performance. Pattinson, whose mere presence will introduce the film to an undiscerning legion of acolytes happy to follow wherever he may tread, is used sparingly here, though strikes a formidable figure in what’s meant as the final reveal.

Corbet and Fastvold seem to be using Sartre merely as a jumping off point, since they leave out several important elements from the original short story, including an important pedophile character and an eventual murder. Instead, The Childhood of a Leader seems more fascinated with tendencies, both presenting and denying the usual cinematic clichés of domestic disturbance and the development of right-wing fervor. Much of the unease is merely implied, supplied by an unrelenting and alarming ambience.

The texture and tone of the film earns rightful comparisons to someone like Michael Haneke (with whom Corbet worked on the 2007 version of Funny Games), particularly 2009’s The White Ribbon, which shows the development of a generation who would allow Nazism to be born out of Protestantism. Likewise, both film and source material court comparison to Alfred Doblin’s 1929 novel Berlin Alexanderplatz, and the prescient re-tooling of the material by Rainer Werner Fassbinder for his famed 1980 television mini-series adaptation. Tasty nuggets of doom prevail throughout the dialogue, in reference to evil’s stronghold more of an issue concerning how “so many have not the courage to be good.”

DP Lol Crawley (Andrew Haigh’s 45 Years) frames many shots with an incredible field of depth, subjects appearing to be buried within the rooms of the ominous palatial residence, doorways flung open like layers to a deep pit (and revel in all the fantastic set decorations—the fabric on the monolithic curtains becomes a recurring visual motif). More infamous is a phenomenal orchestral score from none other than Scott Walker, which drew some surly critiques following the film’s premiere at the 2015 Venice Film Festival in the Horizons sidebar (where the film took home Best Debut and Best Director). But the accomplishment of this phenomenal score (which evokes a lost tradition of cinematic accomplishments enhanced by musical artists) here leads The Childhood of a Leader to the fever pitch of delirium, and an epilogue with a shorn Robert Pattinson (bereft of the very locks which caused what is meant to be a shameful moment of gender confusion early on) blasting the camera into a careening, unstoppable tailspin.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆