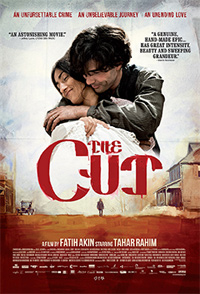

Third Cut is the Deepest: Akin’s Barren Examination of Armenian Genocide

Turkish-German director Fatih Akin concludes his decade in the making ‘Love, Death, and the Devil’ trilogy with The Cut, a film documenting the devastation of the 1915 Armenian genocide. It is the second film to reach theatrical release in 2015 dealing with the century old tragedy, following the aptly titled 1915 directed by Garin Hovannisian and Alec Mouhibian (both films notably star French-Armenian actor Simon Abkarian), and does convey a certain sense of nobly epic proportions in regards to the detrimental scope of an event robbed of the same historical urgency as several genocides since. But the nature of these horrors are lost in Akin’s overly refined handling of the material, whittled down to one father’s ceaseless journey to reclaim the kin war has separated him from. Those unlikely to appreciate a certain sense of honorable intention in Akin’s epic will perhaps find its stretches of monotony to make for a rather underwhelming finale, though a sometimes strenuous running time of nearly two and a half hours doesn’t help matters much.

Turkish-German director Fatih Akin concludes his decade in the making ‘Love, Death, and the Devil’ trilogy with The Cut, a film documenting the devastation of the 1915 Armenian genocide. It is the second film to reach theatrical release in 2015 dealing with the century old tragedy, following the aptly titled 1915 directed by Garin Hovannisian and Alec Mouhibian (both films notably star French-Armenian actor Simon Abkarian), and does convey a certain sense of nobly epic proportions in regards to the detrimental scope of an event robbed of the same historical urgency as several genocides since. But the nature of these horrors are lost in Akin’s overly refined handling of the material, whittled down to one father’s ceaseless journey to reclaim the kin war has separated him from. Those unlikely to appreciate a certain sense of honorable intention in Akin’s epic will perhaps find its stretches of monotony to make for a rather underwhelming finale, though a sometimes strenuous running time of nearly two and a half hours doesn’t help matters much.

In 1915 Mardin, blacksmith Nazaret Manoogian (Tahar Rahim) is busy grappling with his class resentment while caring for his wife (Hindi Zahra) and twin daughters Lucinee and Arsinee (Dina and Zein Fakhoury). In the swiftly changing political landscape going on around them, the Ottomans suddenly join WWI and all Armenian men are immediately recruited. Jostled out of bed in the middle of the night, Nazaret is separated from his wife and daughters and forced to work as a road builder in the desert. After a year of toiling, a gang of bandits executes the crew of road builders, but one thief (Bartu Kucukcaglayan) is a reluctant murder, sparing Nazaret by only gashing his neck with the titular cut, which turns him into a mute. Scraping along until the end of the war in 1918, he eventually finds his sister-in-law, only to learn his wife died. Eventually, he receives word his daughters survived and were wed, and so he begins a monumentally staged journey across continents to track them down.

Compared to the other two chapters of Akin’s somber trilogy dealing with Turkish culture scrambling for a stronghold in foreign territory, The Cut unfortunately feels like the weakest of the three, modeled after the crushing scope of classic David Lean epics like Doctor Zhivago or Lawrence of Arabia. A father’s search for his potentialy honorably compromised daughters bears a slight resemblance to John Ford’s The Searchers template, as well. But with Akin’s Head-On (2004) taking home the Golden Bear at Berlin, and 2007’s follow-up The Edge of Heaven winning Best Screenplay at Cannes, the Venice premiered The Cut was met with a stinging, frosty reception (which followed earlier headlines in 2014 out of Cannes confirming Akin had been locked out of a main competition slot).

So it appears a muted reception has long been in store for Akin’s latest, which is certainly a beautiful piece of film to behold (featuring the returning DoP Rainer Klausmann), but lacks the emotional stronghold plainly evident in something like The Edge of Heaven. A score from Alexander Hacke lends the film a more modern feel, though it sometimes escapes from its electro-based meditative perch to instead recall something we’d expect to hear in a giallo film. Notably, the film was co-written by Mardik Martin, who hasn’t written a feature since co-writing Martin Scorsese’s features Mean Streets (1973), New York, New York (1977), and Raging Bull (1980), which may explain Scorsese’s very vocal championing of the film.

Featuring footage from Chaplin’s classic The Kid (1921), which Nazaret watches right before learning his daughters survived the war, Akin makes it clear he wishes us to align the tragically muted protagonist with the timeless, melancholy tramp—at least in a sense of the emotive capabilities of the visual arts. Except, as determined a performance as Tahar Rahim gives, his eternal silences lessens the intensity of The Cut.

Following a few brief, brutally violent sequences early on, there’s not much to grapple with as Nazaret wanders through endless locales (from Syria, Lebanon, Cuba, Florida, and Minneapolis) except to witness him realize basic lessons, such as how his own actions can add to the mayhem (like seeing a young child pummeled with a rock in the midst of angry demonstration as the Ottoman’s flee) or help those in need (such as saving a young Native American woman from being raped, even to his own detriment). These various locations allow for a variety of international stars to pop up in brief succession, such as Akin regular Moritz Bleibtreau, Danish actress Trine Dyrholm and Canadian-Armenian actress Arsinee Khanjian (in a rare appearance outside of her husband Atom Egoyan’s films).

Undoubtedly, The Cut touches on important events certainly worthy of cinematic representation, but this epic display tends to swallow the subject’s potency. But then, they always say the devil’s in the details, so maybe that’s the point.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆