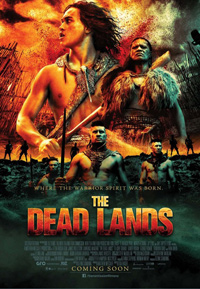

Dead and Buried: Fraser’s Sumptuously Filmed, Familiar Revenge Drama

Premiering at the Toronto Film Festival and snagging the distinction of representing New Zealand as the official best foreign language selection in 2014, Toa Fraser’s The Dead Lands is the first film to be shot entirely in the Maori language and to be told entirely from their character perspective (and not in their relation to white characters). That the narrative is entirely derivative, and with a brutality that will put one, peripherally, in mind of Apocalypto (yes, that Mel Gibson about the Mayans) is sometimes easy to overlook considering the film’s vibrant palette. But as well intentioned as these honorable characterizations are intended in Glenn Strandring’s script, on film they are shapeless archetypes of good vs. evil in an endless cycle of violence brought to a wishful thinker’s fantastical resolution.

Premiering at the Toronto Film Festival and snagging the distinction of representing New Zealand as the official best foreign language selection in 2014, Toa Fraser’s The Dead Lands is the first film to be shot entirely in the Maori language and to be told entirely from their character perspective (and not in their relation to white characters). That the narrative is entirely derivative, and with a brutality that will put one, peripherally, in mind of Apocalypto (yes, that Mel Gibson about the Mayans) is sometimes easy to overlook considering the film’s vibrant palette. But as well intentioned as these honorable characterizations are intended in Glenn Strandring’s script, on film they are shapeless archetypes of good vs. evil in an endless cycle of violence brought to a wishful thinker’s fantastical resolution.

Wirepa (Te Kohe Tuhaka), the young leader of a bloodthirsty, aggressive tribe with lots he apparently has to prove, sabotages the graveyard of his own ancestors and blames the sacrilege on Hongi (James Rolleston), the young son of a more peaceable nearby tribe. Refusing any amends, Wirepa’s warriors storm Hongi’s tribe and mercilessly slaughter everyone except Hongi, who manages to escape. Vowing vengeance for his father’s murder, Hongi flees into the Dead Lands, an area that once belonged to a prosperous people that mysteriously disappeared. All fear entering it, but Hongi’s hand is forced, which brings him into the presence of the supposed demon ruling the region (Lawrence Makaore). The warrior realizes that Hongi is in the same position as himself and vows to assist him as Wirepa follows in pursuit.

At times, the attractiveness and fine grooming of several cast members (as in those big pearly white teeth) makes this feel akin to a stylized Hollywood production, particularly Te Kohe Tuhaka as the villainous Wirepa. Some of the actors are not Maori, and it manages to be not readily apparent, though the real standout is Lawrence Makoare, who was featured in Peter Jackson’s first round of Tolkien in the Lord of the Rings trilogy. As the dreaded monster that inhabits the eponymous lands, he’s the only character given any real depth, struggling through a lonely existence, unable to forge connections because that would mean ending the mysterious legend that has kept him alive, the last surviving member of his people. As our main protagonist Hongi, James Rolleston doesn’t make much of an impression, given a predictable trajectory of a wronged boy becoming a man as he seeks retribution for his family’s slaughter.

Leon Narby’s cinematography (who worked on Whale Rider as well as Fraser’s previous three features) makes excellent use of New Zealand’s sumptuous landscape, while Don McGlashan’s prominent score lends a certain bloodthirsty ambience. Those familiar with Fraser’s previous works (like the incredibly sappy 2008 film My Talks With Dean Spanley) may be pleasantly surprised at the level of intensity accomplished here, but its frequent action sequences sometimes often underwhelm.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆