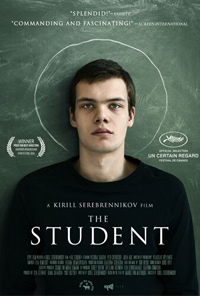

Class Act: Serebrennikov Illustrates the Perils of Fundamentalism

Kirill Serebrennikov, one of several rising auteurs from Russia’s troubling political regime, reaches his widest platform yet with fourth feature, The Student. A moral drama which examines the toxic fallout of fundamentalist stances, the film’s droll attitude and straightforward presentation neatly obscures its progressive, subversive themes in plain sight with a narrative which ends up being considerably daring (despite the artlessness of its title). Uncoiling with increasingly vehement attitudes, (think the Christian tinged version of little Rhoda Penmark from psychological horror classic The Bad Seed) and you tap into this peculiarly flavored exercise, which also lucidly conveys the kind of dark comedic social commentary often sanctioned heavily from Russia’s contemporary conservatism and staunch rigidity. As a last ditch effort to avoid participating in the swimming course of gym class, a sociopathic loner sees the inherent power in contradicting authority through the manipulations of religious piety, thereby unnerving and troubling high school staff members who are unsure of their level of control versus kowtowing to archaic, fearful ideologies.

Kirill Serebrennikov, one of several rising auteurs from Russia’s troubling political regime, reaches his widest platform yet with fourth feature, The Student. A moral drama which examines the toxic fallout of fundamentalist stances, the film’s droll attitude and straightforward presentation neatly obscures its progressive, subversive themes in plain sight with a narrative which ends up being considerably daring (despite the artlessness of its title). Uncoiling with increasingly vehement attitudes, (think the Christian tinged version of little Rhoda Penmark from psychological horror classic The Bad Seed) and you tap into this peculiarly flavored exercise, which also lucidly conveys the kind of dark comedic social commentary often sanctioned heavily from Russia’s contemporary conservatism and staunch rigidity. As a last ditch effort to avoid participating in the swimming course of gym class, a sociopathic loner sees the inherent power in contradicting authority through the manipulations of religious piety, thereby unnerving and troubling high school staff members who are unsure of their level of control versus kowtowing to archaic, fearful ideologies.

Nagged by his mother for his bad grades and adamantly refusing to participate in gym class, brooding teenager Venya (Pyotr Skvortsov) concocts a scheme to get out of scholarly requirements by claiming it’s against his religion. Memorizing Biblical scripture and spouting large chunks of it against school staff with great zeal, Venya quickly takes his new belief system to fanatical heights, attempting to coerce more gullible, vulnerable classmates by indoctrinating them with his Christian beliefs, thereby disrupting his classes. However, he meets a considerable foe in biology teacher Elena (Victoria Isakova).

The specter of communism seems to infect the older generation of characters in The Student, particularly a school principal (Svetlana Bragarnik) who’s clearly uneasy with Elena’s progressive attitudes (even though assuaging the ruffled teacher by stating the opposite). As its title indicates, there are certain expectations of the role of student, here upended by the transparent machinations of Venya, whose religious protestations grant him automatic agency.

Serebrennikov’s film is an interesting counterpart to Czech Republic filmmaker Jan Hrebejk’s The Teacher (2016), set in early 80s Czechoslovakia about a manipulative school teacher who blackmails her students’ parents for special favors. Both these central characters are using social loopholes to secure a better situation for themselves at the expense of ruining a whole system and diminishing the personal and professional lives of those in their wake. Ironically, Elena’s fervent desire to combat Venya affects her detrimentally—she becomes fundamentalist from the opposing standpoint, defying her own controls and acting out just as egregiously (shown stapling her shoes to the floorboards of her class in order to avoid removal). Both teacher and student laboriously memorize their Bibles until both lives are completely, irrevocably consumed.

Many fundamentalist charlatans in cinema have similar psychological profiles, children who are rigidly controlled by their parents and figure out how to utilize such zealotry to their theatrical advantage. Whether Aimee Semple McPherson or the Elle Fanning character in Live By Night, the religious revivalist is consistently a dangerously persuasive force. The Student portrays the opposite of the norm, Venya clearly rebelling against a mother more carelessly doting than domineering. As a biology teacher, Elena is unfortunately ground zero for the battles waged against progressive scientific thought. Her attempts to discuss evolution and sex education devolve into chaos, leading her into a personal crusade against Venya (which consists of her own personal theory of Jesus Christ and his apostles’ possible homosexuality).

Based on a play from German scribe Marius von Mayenburg, The Student is an overwhelming firestorm of Biblical scripture lobbed precipitously between the film’s sparring parties. Victoria Isakova gives a mightily sympathetic performance as a woman of Jewish heritage whose dogmatic resistance to little Venya’s masquerade. She’s the only figure in a largely female institution brave enough to challenge concepts from a culture which continues to relent to masculine, patriarchal traditions (which for her also means sacrificing her romance with her gym teacher colleague) despite everyone realizing the ridiculousness of the situation. Serebrennikov often shows the principal making light of the teacher/student conflict even though citing Elena for her progressive, combative reactions. Even Venya’s atheist, hysterical leaning mother (Julia Aug) can see through her son’s superficial ideations.

Gender and sexuality are the subversive cornerstones of The Student, which makes this material more daring than even most contemporary American features attempting to examine similar ground. Sexuality is particularly underlined, as when Venya rebuffs the advances of a sexually aggressive female yet tolerates, and even fosters a physical connection with a crippled classmate who becomes his all too willing disciple, even in concocting murder. Based on Putin’s enforcement of religious doctrine in Russia’s education system, not to mention his enthusiastically homophobic beliefs, the bravura of a film like The Student is impossible to ignore. Enhanced by a meticulous and offbeat soundtrack, DP Vladislav Opelyants ratchets anxiety and tension terrifically within his frames through long tracking shots which become as frustratingly taxing as they are visually astute. Like a contemporary moral fable, The Student is an excellently postured predicament, languidly brooding over its clutch of unhappy characters.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆