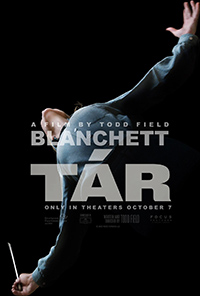

Notes on a Scandal: Blanchett Swallows Berlin in Exceptional Psychological Drama from Field

It’s been sixteen years since Todd Field’s last film, the arduous Academy Award-nominated melodrama Little Children (2006), his follow-up to the lauded In the Bedroom (2001). While plenty of rumored projects from the director have withered away throughout the years, he’s returned with TÁR, a narrative conceived entirely for Cate Blanchett, who rips through the material like a ravening lion. Truly one of the most dazzling characterizations ever committed to film, whatever the gender categorization, Blanchett is spellbinding as a narcissistic orchestra conductor whose pride reaches the veritable heavens before leading her to ruin.

It’s been sixteen years since Todd Field’s last film, the arduous Academy Award-nominated melodrama Little Children (2006), his follow-up to the lauded In the Bedroom (2001). While plenty of rumored projects from the director have withered away throughout the years, he’s returned with TÁR, a narrative conceived entirely for Cate Blanchett, who rips through the material like a ravening lion. Truly one of the most dazzling characterizations ever committed to film, whatever the gender categorization, Blanchett is spellbinding as a narcissistic orchestra conductor whose pride reaches the veritable heavens before leading her to ruin.

While a despicably abused, hyperbolic word like ‘powerhouse’ has been bandied about so long it’s meaningless, it should have been the word either coined or reserved for her ferocious achievement as Lydia Tar. From Berlin to New York to Thailand, it’s a characterization of unparalleled scope and depth for Blanchett as a thorny human who might be utterly unlikeable but who’s unarguably admirable for her unapologetic tenaciousness.

We’re introduced to the marvel that is Lydia Tár (Blanchett) as she is giving an interview which gives us an overview of her esteemed career prior to the publication of a book detailing her accomplishments, Tár on Tár. An EGOT recipient, she’s also the first-ever female conductor of a German orchestra, the esteemed Berlin harmonic, a city in which she lives with her violinist partner Sharon (Nina Hoss) and their young daughter, Petra. Although she’s demure about her accomplishments, in real life she’s well aware of her power and position, on the verge of making some drastic shifts in the culture she’s commanded for the past seven years by replacing her workmanlike Assistant Conductor, Sebastian (Allan Corduner), who was in place with her predecessor (Julian Glover). Olga (Sophie Kauer), a new temporary cellist who’s joined the philharmonic, has caught Lydia’s eye, and she pulls significant strings, making unorthodox decisions to secure her as a soloist in an upcoming recorded concert of Mahler’s fifth symphony. Lydia is on the verge of being the first woman to record Mahler’s complete catalogue, saving the most complex of Mahler’s works (a composer whose reverence she shared with her mentor, Leonard Bernstein) for the last, which had been interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it seems Lydia’s behavior towards Olga isn’t exactly abnormal as a history of questionable boundary issues with previous students is soon to haunt her. With her assistant Francesca (Noemie Merlant) patiently waiting consideration to assume the position of Assistant Conductor, it seems a past stint in Peru with Francesca and another student, left some residual strings attached. With Lydia having sabotaged said student’s chances at career opportunities due to clingy, emotional behaviors, the student’s suicide suddenly jeopardizes her looming achievement. But not even Lydia anticipates the carnage she’s about to contend with.

The initial interesting complication, which is somewhat superficial, is the argument of how a character like Lydia would be perceived if she were a man, even though historically and creatively we’ve seen such a composite. Though they’re wearily condemnable, such men may be critiqued but are often condoned as culturally acceptable, a given blight in a global heteropatriarchy of established canons, etc. Lydia isn’t simply behaving as a man would, despite adopting masculine roles (she introduces herself as Petra’s father to a child she threatens on behalf of her daughter) and emanating the swagger of breadwinner in her personal life—-she’s simply a person who’s grown accustomed to power in such a way it highlights her worst tendencies, which gradually run amok. Like most people, only a significant combination of ‘the powers that be’ hobble her eventually, but there’s never a predictable moment in either the narrative or her cool, calm, collected reflexes.

What’s even more interesting in TÁR is what happens after the film’s ‘climax.’ In a state of retreat, we get the briefest glimpse of her past, and we realize Lydia is completely accustomed to a scorched earth methodology. Intriguingly, she knows how to start from scratch, a hint we get early on in an interview in which she reacts to the word ‘varied.’ She’s a phoenix who’s risen from the ashes before, and as we watch her drift down Thailand’s Mekong River, Field supplies an off-the-cuff tidbit about the crocodiles who’ve taken up residency thanks to several of them escaping from a Marlon Brando film decades before (likely 1963’s The Ugly American). Little do they realize another predator has been unleashed in their ecosystem.

Initially, it’s a joy to take in Blanchett’s ruthless behavior, even if her utter lack of sympathy announces her undoing, such as a heated exchange at Juilliard class, where Lydia picks apart Max, a non-binary BIPOC student who loathes Bach’s personal life and refuses to acknowledge the composer’s creative contributions. While both sides have points to make, she’s brutal in her pretentious jabs. Field makes us work through brief tidbits of information to understand what it is Lydia has done to instigate the suicide of a former student, who she apparently had a sexual dalliance with in Peru during a notable work assignment alongside Noemie Merlant’s Francesca, the indefatigable assistant who’s stuck by Lydia’s side in hopes to be promoted to Assistant Conductor. It appears Lydia is not only accustomed to scorched earth but also, by necessity, burning bridges.

Arguably, all the supporting cast members both in front of and behind the screen are eclipsed by Blanchett’s titanic performance, but Nina Hoss (who played a similar role in 2019’s The Audition) as her violinist partner is a flurry of complex facial expressions, left in the dark to Lydia’s paramount personal secrets. Julian Glover plays a mentor who previously held Lydia’s post, a scion of previous generation who were able to more easily elude similar condemnations, and an impressive Noemie Merlant exudes a fluctuating mixture of emotional responses to Lydia’s behavior. The film opens with a screenshot on a cell phone critiquing Lydia, the culprit eventually revealed as Francesca, whose love/hate relationship with her mentor assists in her fall from grace (and ends up being the conduit to the platform responsible for rallying a public outcry against Lydia, the noxious social media she so smugly and tritely disdains.

Mark Strong is on hand for a trio of scenes as a fellow conductor eager to siphon from Lydia’s craft, unwittingly becoming the target of her unhinged violence in a scene rivaling the terrible power of Isabelle Huppert in The Piano Teacher (2001). Lensed by Florian Hoffmeister (Antlers, 2021) with an original score from Hildur Guðnadóttir (Joker, 2019), it’s a technically impeccable achievement on all fronts, lending an increasing sense of menace as Lydia gets back into a corner of her own making. Field’s script is impeccably studied and researched (at least to the uninitiated) in this specific universe, conversations and references and processes given a free-ranging, heady realm for the audience to decipher as the narrative moves along.

TÁR is like a studio-era women’s picture but orchestrating the fallout of The Towering Inferno—with Blanchett giving the rip-roaring energy of a Bette Davis or a Joan Crawford if they’d ever been outfitted with an exceptionally articulate freedom to give a hearty fuck you to what anyone thinks both within and outside of the frame containing them. In one of Lydia’s few moments of vulnerability, she watches a segment of Leonard Bernstein from a 1960s clip where he explains to the audience how music allows us to channel and experience feelings we can never put into words—-it’s a similar statement one could make for a film like TÁR, about a person who generates a dizzying intersection of thoughts and emotions words can’t properly express, but we know in our gut is a rare, troubling, and glorious film.

Reviewed on August 31st at the 2022 Venice Film Festival – In Competition. 158 Mins.

★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆