Declaration of Poor: Donzelli’s Tone Deaf Survey of a Starving Artist

Despite honorable intentions, it’s difficult not to perceive Valérie Donzelli’s latest feature, At Work (À pied d’oeuvre), as an aggravating slice of poverty tourism. Based on the 2023 publication by Franck Courtès, a photographer who abandoned his lucrative career to pursue writing and eventually finds success with this auto-fiction/memoir, the author’s own personal experiences courting poverty to support his passion likely feels more profound in print than with this well-intentioned reenactment. With a script co-written by Gilles Marchand (a writer/director more well-versed in genre fare, such as 2003’s Who Killed Bambi? and 2022’s The Night of the 12th), the film’s aspirations are trapped in what feels like a flawed sociological experiment from a privileged vantage point. It feels as if Courtès and Donzelli believe they’ve uncovered a hidden truth about harsh economic disparities invisibly turning the wheels of capitalism. But all this really reveals is the perennial shock experienced whenever bourgeois bubbles are compromised.

Despite honorable intentions, it’s difficult not to perceive Valérie Donzelli’s latest feature, At Work (À pied d’oeuvre), as an aggravating slice of poverty tourism. Based on the 2023 publication by Franck Courtès, a photographer who abandoned his lucrative career to pursue writing and eventually finds success with this auto-fiction/memoir, the author’s own personal experiences courting poverty to support his passion likely feels more profound in print than with this well-intentioned reenactment. With a script co-written by Gilles Marchand (a writer/director more well-versed in genre fare, such as 2003’s Who Killed Bambi? and 2022’s The Night of the 12th), the film’s aspirations are trapped in what feels like a flawed sociological experiment from a privileged vantage point. It feels as if Courtès and Donzelli believe they’ve uncovered a hidden truth about harsh economic disparities invisibly turning the wheels of capitalism. But all this really reveals is the perennial shock experienced whenever bourgeois bubbles are compromised.

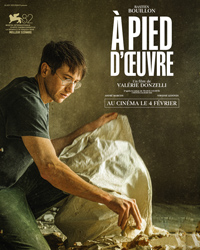

Paul Marquet (Bastien Bouillon) was a successful photographer who left it all behind to pursue writing. However, though his books have been well reviewed, he’s not exactly a best-selling author. After the failure of his third novel, his publisher (Virginie Ledoyen) announced they will not be publishing his fourth novel, Story of an End, a break-up narrative detailing his own recent divorce from his wife (Donzelli), who has just moved to Montreal with their two teenage children. But Paul is struggling financially, and despite the urging of his father (André Marcon), rents a studio flat from a close family friend and begins to work as an ersatz handyman for ridiculously low wages on a job app connecting those offering such services to clients around the city. These experiences lead to a breakthrough for Paul in his writing, inspiring a new manuscript his publisher rushes to the press.

The lyrics of Pulp’s track “Common People” comes to mind throughout At Work, as, literally, if he called his dad he could stop it all. The French language title translates as On the Job, which feels more ironic since the protagonist is certainly not accustomed to the idea of working smarter, not harder. We never quite learn why his wife (Donzelli playing a rather unsympathetic woman) left him, but it would appear her preference for the finer things in life might have had something to do with it. Her refusal to read any of her ex-husband’s novels for fear of discovering something unpleasant is the only indication of their shared experiences as repressed elitists who clearly have no idea about what struggling to get by actually looks like. It’s not quite explained why Paul still can’t take photographs here and there to support himself while he writes.

As the composite Paul Marquet, it’s also unclear what experiences would merit publication or public interest. Bouillon is never given anything distinctive to do, his experiences both random and repetitive in his confrontations with employees utilizing what feels like a Hunger Games inspired trap to exploit the lower rungs of the working class. As presented here, we’re meant to believe his expose of working with what feels like a contemporary sweat shop design, “Jobber,” has a similar importance to something like Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel & Dimed, where she details her experiences as an undercover journalist in occupations designed for the working poor. Though there’s acknowledgment in Paul’s narration that he excelled in this ‘working’ environment because his carefree attitude of not feeling entirely beholden to it was appealing to a segment of his ‘employers,’ it’s curious there’s no unpacking of what kind of people seek to employ laborers for unfair wages. While there are wealthy cheapskates willfully oblivious to exploitative tactics, a certain component of the people who hire Paul are also struggling themselves and cannot afford to pay for services which guarantee the results they desire.

To compare At Work to something like the working class woes proliferating the contemporary cinema of the Dardenne Bros., Ken Loach or Stephane Brize, it’s clear there’s a formidable lack of self-awareness in scope. Films like Bicycle Thieves (1948), A Better Life (2011), or the more recent Souleymane’s Story (2024) delve into the palpable fear, danger and despair defining the lives of those just trying to get by day-to-day. Despite some tender moments of kindness thrown Paul’s way (including a meaningful exchange with his son), it’s unclear what we’re supposed to feel about Paul’s experience, or why we’re supposed to care considering he willfully lived an uncomfortable existence in a faux struggle only to profit from the experiences by the sale of his book. As such, it’s a film which feels audaciously removed from the very experiences it believes to profoundly ponder.

Reviewed on August 29th at the 2025 Venice Film Festival (82nd edition) – In Competition. 92 Mins.

★★/☆☆☆☆☆