Trials of Faith Without Error; Glesson’s Good Priest Suffers for Sins of the Fathers

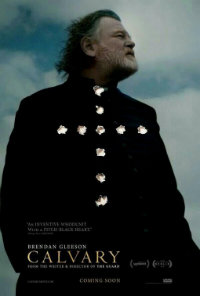

Two years after The Guard, the most commercially successful Irish film of all time, writer-director John Michael McDonagh and actor Brendan Gleeson return with considerably darker arthouse fare. Part Two of the unfinished “Glorified Suicide Trilogy”, Calvary begins inside a shadowy confessional with the announcement, “I first tasted semen when I was seven years old”. To the voice behind the lattice, Gleeson’s priest replies, “Certainly a startling open line” – speaking, more or less, on behalf of Calvary’s wrong-footed audience. The recollection of sexual abuse precedes a heavy dose of theological and moral insight, but lively, quick-witted dialogue will sweeten the pill.

Two years after The Guard, the most commercially successful Irish film of all time, writer-director John Michael McDonagh and actor Brendan Gleeson return with considerably darker arthouse fare. Part Two of the unfinished “Glorified Suicide Trilogy”, Calvary begins inside a shadowy confessional with the announcement, “I first tasted semen when I was seven years old”. To the voice behind the lattice, Gleeson’s priest replies, “Certainly a startling open line” – speaking, more or less, on behalf of Calvary’s wrong-footed audience. The recollection of sexual abuse precedes a heavy dose of theological and moral insight, but lively, quick-witted dialogue will sweeten the pill.

In McDonagh’s words, it’s “Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest with a few gags thrown in”. To give a sense of these gags – Father Timothy Leary (David Wilmot) inquires about “fletching” after hearing the word in confession – his character named after the 1960‘s LSD-Guru whose ashes were launched into space.

Calvary plays like a whodunnit (or rather who’sgonnadoit), with the reverse construct of Hitchcock’s I Confess. The unknown parishioner vows to murder the virtuous Father James on the following Sunday – because his abuser, safeguarded by status, had died without suffering reprisal. Besides, the vengeful stranger says, “there’s no point in killing a bad priest”. His rationale – that murdering a good priest is the only way to shake the Irish Catholic community – accounts for Calvary’s successful handling of its real-world inspiration.

We expect a film confronting recent abuse scandals, those in Ireland and across the world, to render its priestly protagonist a monster – but to our surprise, Gleeson’s character is actually a good man. Identifying the crisis with one sadistic individual or isolated incident has only misdirected the conversation. Calvary finally points to the reality of innumerable Catholic sex-abuse cover-ups, to the institutional smoke screen that has normalized predatory practices for several generations of clergy. Father James is not the idyllic counter-image to our rueful reality. He is the brilliantly written, unintended victim of institutionalized sexual violence and its devastating consequences.

Gleeson gives a soulful performance as the tough-minded priest with one week to settle affairs. As the seven-day clock ticks, a reference to the stages of grief, Father James makes his usual rounds, introducing us to the large ensemble cast of idiosyncratic parish members. His depressive daughter Fiona (Kelly Reilly) visits from London, having recently made the “classic error” of cutting across. We come to learn that Father James joined the priesthood when Fiona’s mum passed, leaving her with unconquerable feelings of abandonment. An imperfect parent, ex-husband, and recovering alcoholic – our hero didn’t come straight from the seminary, making it easier to trust him as a moral authority.

Cruisin’ around in a red convertible with his beloved golden retriever riding shot-gun, Glesson’s character is convincingly human, soutane and all. He even drops the F-bomb, having reached wit’s end with Dr. Frank Harte (Aidan Gillen), the atheist hospital medic with a penchant for widows and “purely medicinal” crack cocaine. His stories about victims of freak accidents are awful, but Father James is constantly under this sort of emotional assault. The promiscuous Veronica Brennan (Orla O’Rourke), wearing Jackie O glasses to shade her black-eye, gets a great thrill out of provoking the priest. Her lover Simon (Isaach de Bankolé), the town mechanic, is an African immigrant quick to bemoan the ministry’s colonial history. Angered by the church’s unchecked involvement in everyone’s personal lives, he resorts to threats of physical violence. Milo Herlihy (Killian Scott) has a similar sinister streak. Feeling murderous after exhausting the possibilities of pornography, Milo’s self-prescribed options include committing suicide or joining the military, provoking a world-wise comment about the “inherently psychopathic” nature of enlisting.

Also worth a mention from the somewhat overstuffed roaster of bawdy characters is Michael Fitzgerald (Dylan Moran), a sickeningly wealthy dissociative and the rightful owner of Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors. Suspend your disbelief and watch Mr. Fitz take an iconoclastic whizz all over the masterpiece; but to be fair, McDonagh is not just taking the piss. Cleverly referenced, the painting’s anamorphic skull, famously cited by psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, is a reminder of mortality in tension with the ambassadors’ material comforts.

More cause to be convinced of McDonagh’s fluency in the arts is provided in scenes with local butcher Jack Brennan (Chris O’Dowd). Raw meat hangs from the ceiling, stirring visceral anxieties in the manner of Francis Bacon. Notably, the Irish-born artist’s 1954 painting Figure with Meat, part of a larger series, is based on Velázquez’s portrait of Pope Innocent X. Church authorities speak of salvation, but suffer the same terror of knowing, as Bacon said, that “we are potential carcasses”. Then there is imprisoned murder-rapist Freddie Joyce (acted, oddly enough, by Gleeson’s son Domhnall), who compares the taste of human flesh to pheasant – a bit “gamey”. Father James treats him with an alarming degree of dignity – considering his history of cannibalizing young girls, but how does one reconcile with the idea of a merciful God?

If Father James keeps faith, there is still physical fear – like The Seventh Seal’s Antonius Block said to Death: “My body is afraid, but I am not”. As he finally comes face-to-face with his appointed death, the mise en scène resembling Caspar David Friedrich’s “The Monk by The Sea” imparts an excruciating sense of loneliness. Much like the meager figure subsumed by landscape in the German Romantic oil painting, the solitary priest’s physical presence shrinks against weather-beaten terrain. Father James appears vulnerable in the vastness of nature – but what’s worse is his insignificance in the face of God, as cinematographer Larry Smith’s swooping ariel shots endow the coastal landscape of Siglo with divine authority. Owing to Mark Geraghty’s color-conscious production design, the film’s interior-shots also have a painterly quality.

Clearly an aesthete with a nose for intertexuality, auteur-bound McDonagh’s disciplined sophomore feature culminates in the Bergmanesque line: “there’s too much talk about sins and not enough talk about virtues”. Loaded with blackly comic bits never trivialize faith-shaking brutalities of the world, Calvary offers something smart to consider, for both believers and skeptics alike.

Reviewed on January 20th at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival – Premieres section. 100 Mins

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆