It’s a Non-Refundable Life: Baumbach Explores the Sacrifices of Fame

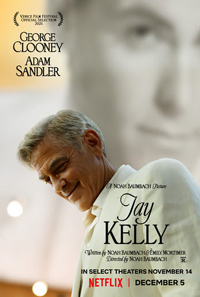

George Clooney headlines what could be interpreted as an approximation of his own experiences in Noah Baumbach’s Jay Kelly. Resembling, in many ways, an old-fashioned Hollywood star vehicle exaggerating both the highs and lows of a matinee idol’s Faustian sacrifices, it’s the comedic male equivalent of Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard (1950) or Bette Davis in The Star (1952), except with a finale tapping into what’s supposed to be profound rather than degrading. Baumbach, who has increasingly dabbled in glossy portraits of dysfunction over the past decade with films like While We’re Young (2014) and The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) (2017), somehow feels as if he’s lacking the main ingredient necessary to pull this angsty comedy together — sincerity. In a film jam packed with notable names and personas, it’s a film which eventually feels less than the sum of its parts. However, those prone to the paralytic trance of Hollywood glitter might be dazzled by its superficial excesses.

George Clooney headlines what could be interpreted as an approximation of his own experiences in Noah Baumbach’s Jay Kelly. Resembling, in many ways, an old-fashioned Hollywood star vehicle exaggerating both the highs and lows of a matinee idol’s Faustian sacrifices, it’s the comedic male equivalent of Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard (1950) or Bette Davis in The Star (1952), except with a finale tapping into what’s supposed to be profound rather than degrading. Baumbach, who has increasingly dabbled in glossy portraits of dysfunction over the past decade with films like While We’re Young (2014) and The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) (2017), somehow feels as if he’s lacking the main ingredient necessary to pull this angsty comedy together — sincerity. In a film jam packed with notable names and personas, it’s a film which eventually feels less than the sum of its parts. However, those prone to the paralytic trance of Hollywood glitter might be dazzled by its superficial excesses.

Jay Kelly (Clooney) has just wrapped filming and is looking forward to spending the summer with his youngest daughter (Grace Edwards) before she goes off to college. However, he’s forgotten she’s scheduled to travel with friends across Europe. He’s further dismayed to learn his old mentor (Jim Broadbent), the director who gave him his first major break, has died. At the funeral, he runs into his college roommate (Billy Crudup), the man who was supposed to play the role eventually offered to Jay. Fisticuffs ensue, and the next day Jay has decided to blow off his next film project to follow his daughter, accepting an invitation received a career tribute award in Tuscany as an excuse. This causes a chain reaction among Jay’s staff, forcing his manager Ron (Adam Sandler) to drop everything and fly to France and indulge his client, at least long enough to convince him to stay committed to the next film he’s shooting. But Jay is in the midst of a full-blown existential crisis as he begins to realize the extent of the lasting consequences he’s made by focusing on his career rather than personal relationships.

Had Baumbach turned a bit harder (or, at all, really) down a path of actual self-reflection, this portrait of an A-list celebrity at a crossroads could have taken on Dickensian proportions. The various flashbacks into his own memory already feel like we’re stuck on a jag with the Ghost of Christmas past anyway, so why not let’s see beyond that which is only purely self-consuming? These asides should have had the wit of similar devices often utilized by Albert Brooks or Woody Allen. But they are not profound enough to trigger a significant sense of ennui. To be fair, Clooney remains dashing, charming, all of the above. But the only point Baumbach keeps making is how isolating such an existence can be and how utterly obnoxious and soul sucking it is for everyone who has to deal with celebrities professionally or personally. While Baumbach’s last feature was an adaptation of Don DeLillo’s White Noise, it’s a title which seems more fitting for this film.

If Clooney is, technically speaking, sublime casting, so is Adam Sandler, who is the film’s empathetic center as the manager (yes, he takes 15% of his clients’ salaries, how gauche) who not only asks ‘how high?’ when told to jump but also genuinely seems to enjoy dealing with black hole personas. Between these two spectrums are a cascading cast of characters, most of whom are merely adding to a cacophony in the background (Emily Mortimer, Greta Gerwig, Patsy Ferran, Jamie Demetriou, Josh Hamilton, Riley Keough, Isla Fisher, Eve Hewson, Jim Broadbent). Of Kelly’s main entourage, only Laura Dern manages to overcome a stale hokeyness as an outspoken publicist who clearly has a better ability at managing boundaries in an industry which otherwise blurs all significant lines regarding professional expectations. Her character has unfinished romantic business with Sandler’s manager, which is one of many elements feeling tacked on for naught. A strangely wigged Billy Crudup as Kelly’s old roommate, who does some Method acting with a menu, provides some promise, but the conclusion of his scene is so ridiculous it negates the complex meta layers Baumbach stages.

Between tidbits of enjoyable banter, Baumbach stages some of the most comically tone-deaf moments of his career, namely a train sequence where Jay Kelly gets down with public admirers as he awkwardly chases his youngest daughter (Grace Edwards, in a particularly grating role as an oblivious wunderkind) from France to Italy. A stunt involving a German biker who resorts to petty theft when he’s not taking his medication (Lars Eidinger) feels particularly silly. On a more positive note, a gruff Stacy Keach as Kelly’s onerous father is a sight for sore eyes while Alba Rohrwacher, as an exuberant representative of the Tuscan tribute committee, supplies a giddy comedic hue the rest of the film tries to conjure but cannot.

But through it all, we have Jay “Can I Have One More Take” Kelly, a self-obsessed gas bag who can’t realize everyone around him is basically sick to death of him. Except Ron, who gets too nice of a paycheck to complain too loudly. It’s not so much a role Clooney was born to play, but rather, one it makes sense that he is as one of the final surviving major stars of his generation (and kind of resembling what Tyrone Power could have grown into had he lived past the age of forty-four). In the words of Mary J. Blige, the life of Jay Kelly is “just fine, fine, fine, fine, fine, fine.”

Reviewed onAugust 28th at the 2025 Venice Film Festival (82nd edition) – In Competition. 132 Mins.

★★/☆☆☆☆☆