Smack dab in the middle of the age of excess, Albert Brooks’ third directorial feature Lost in America (1985) opened theatrically, a satirical portrait of a mutated, contemporary American Dream as merely a facet of the ‘grass is always greener’ syndrome. Exploring the notion of finding happiness outside of the capitalistic system locking Americans into a frenzied occupational racetrack where more can only lead to a lust for more, Brooks’ film arrived before Gordon Gekko assuaged our guilt with his “Greed is good,” mantra and the notion of solidarity amongst women in the workplace was revealed as fantasy in Working Girl (1988).

Smack dab in the middle of the age of excess, Albert Brooks’ third directorial feature Lost in America (1985) opened theatrically, a satirical portrait of a mutated, contemporary American Dream as merely a facet of the ‘grass is always greener’ syndrome. Exploring the notion of finding happiness outside of the capitalistic system locking Americans into a frenzied occupational racetrack where more can only lead to a lust for more, Brooks’ film arrived before Gordon Gekko assuaged our guilt with his “Greed is good,” mantra and the notion of solidarity amongst women in the workplace was revealed as fantasy in Working Girl (1988).

Like the Griswold’s on an extended vacation, a yuppie couple fed up with the gilded hamster wheel of corporate Los Angeles decide to drop off the map by selling all their earthly belongings and living out their days in a Winnebago as they drive across American a la Easy Rider.

After failing to achieve the promotion he believed he deserved in his Los Angeles advertising firm, thirtysomething David (Brooks) convinces wife Linda (Julie Hagerty) to quit her job (which she is equally unenthusiastic about), back out of escrow and explore America like free-spirited hippies. Selling their worldly goods, the childless couple say goodbye to their old friends and take a pit-stop in Vegas to renew their wedding vows. But when their plans are derailed by an unexpected episode courtesy of Linda, they find themselves navigating their dream under extraordinarily different circumstances.

Brooks opens his film as the voice of Larry King interviewing New York Observer critic Rex Reed drifts through the hallways of the home they’ve just sold. The ceaselessly snarky and hypocritical Reed languishes in the pretension of his craft by explaining his favored way to view a film (in a theatrical venue, all alone), dismissing press screenings filled with the fodder of studio employee relatives and their exaggerated responses as the kind of ‘mass hysteria’ he doesn’t condone.

Fielding a question from an admiring fan, who goads Reed into a conversation concerned with the need for more good old-fashioned wholesome films without nudity, Brooks’ decision to open Lost in America with this segment is intriguing. Reed’s suggested self-loathing (which is imbued with the same ‘Make America Great Again’ sentiments currently and continually plaguing us) in these statements almost goes without saying, a homosexual culture vulture (and star of the doomed adaptation of Gore Vidal’s Myra Breckinridge) extolling a preference for G-rated, heteronormative films of yore, where lust was an imagined projection on the faces of its actors.

Of course, the film Brooks and Hagerty’s characters are inspired by arrived during a cultural upheaval, at the end of the 1960s, which laid to rest the censorship model of cinema with the death of the Hays Code in 1968. In their minds, David and Linda believe they are imitating Peter Fonda’s posse of hippies, except still decked out in their yuppie ideals and privileged comforts. And yet, they are on a similar wavelength as Reed and his oxymoronic understanding of his profession as Americans convinced their toils have a means to an end, until they realize they’re working towards a dream not actually of their own design.

But moving beyond the staggered complexities of its opening moments, Lost in America is an overall exercise in the witticisms of Albert Brooks, although the film’s subject matter has perhaps denied it the same cult reverence as 1991’s Defending Your Life, and is one of Brooks only films not centered on a character involved exclusively with the entertainment industry. Like a swarthy cousin of Woody Allen, Brooks’ seven directorial features to date involve a similar, wisecracking, world weary facet of his own persona.

Lost in America plays like the severely problematic fancifulness which simultaneously underlines the dogmatic adherence to the blinders of privilege, especially as afforded whiteness paired with the socioeconomic advantages of the couple here. This isn’t the committed experiment of the family in Captain Fantastic (2016) or Off the Map (2003), but a derives its gleeful satire from Brooks’ harpooning of a culture which invites the concept of the one percenter, fully realized by those desiring it and arriving as close to its demarcation as they possibly can (if anything, this feels more in tune with the chemistry of Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz in 1953’s The Long, Long Trailer).

Take, for instance, his reaction to his lateral assignment from his boss rather than the promotion he feels he is entitled to (and, for that matter, the eventual resolution to their eventual economic pickle) — these are behaviors considered acceptable in the realm of the heterosexual white men. And if Easy Rider becomes the diegetic motif, it’s a cultural marker (albeit only fifteen years old at this point) already excised from the 1985 zeitgeist, sans the lucky exception of a gung-ho traffic cop who fancies himself equally in tune with the biker fantasy.

There are several other telling moments to the oblivious privilege of David and Linda (and obviously not just the ‘tragedy’ befalling them in Las Vegas), but the repeated fantasy of roughing it in their decked-out Winnebago so they may ‘touch Indians,’ those indigenous phantoms upon whose corpses the country still treads. Even his reaction to Linda’s snafu at the casino (which leads to one of the film’s best scenes, and perhaps best ever use of Garry Marshall), which unfurls at Hoover Dam (the sequence which apparently inspired Nicolas Winding Refn to cast Brooks in 2011’s Drive). But beyond all of the lenses and social perceptions of David and Linda, Brooks and Julie Hagerty make for an appealing on-screen pairing.

While David was a role Brooks originally intended for Bill Murray (who later starred opposite Hagerty in 1991’s What About Bob?), it’s hard to imagine anyone but himself playing this foppish Los Angeles advertising executive, who seems more appropriately (and neurotically) destined for the New York he so willfully seems to disdain. Hagerty remains one of those 1980s comedic gems whose reputation on the stage still precedes her (although besides Brooks’ film and the Airplane! parodies she appeared in several less revered titles worthy of reconsideration, included Altman’s reviled adaption of Christopher Durang’s Beyond Therapy and Howard Brookner’s Bloodhounds of Broadway.

Disc Review:

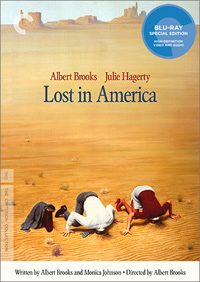

Criterion provides Lost in America (the first Brooks title to join the collection) with a newly restored 2K digital transfer and uncompressed monaural soundtrack. Picture and sound quality are pristine in this 1.85:1 presentation from a new 35mm interpositive made from the original camera negative, while Arizona and its arid unpleasantness gets a lot more screen time than Los Angeles or New York.

Albert Brooks and Robert Weide:

Criterion produced this half-hour conversation between Albert Brooks and filmmaker Richard Wiede in 2017, discussing Brooks’ process for creating characters he would play and his approach to filmmaking.

Julie Hagerty:

Criterion produced this new eleven-minute interview with Julie Hagerty in 2017, where the actress discusses how she was approached by Brooks to play the part of Linda.

Herb Nanas:

Herb Nanas, the longtime manager of Albert Brooks, sits down for this eleven-minute interview with Criterion, produced in 2017, who discusses how he first was introduced to Albert Brooks (who was then known by his family name, Einstein).

James L. Brooks:

Director James L. Brooks (who famously directed Albert Brooks in 1987’s Broadcast News) appears for this fourteen-minute interview produced by Criterion in 2017 and discusses his frequent collaborations with the actor/writer.

Final Thoughts:

Exemplifying the Rolling Stones’ song “You Can’ Always Get What You Want” more than Easy Rider (both creations of 1969), Brooks’ Lost in America is a well-directed and effortlessly entertaining satire of the Reagan era.

Film Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆