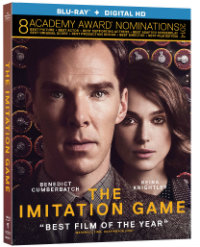

Shut out at the BAFTAs, and nominated for eight Academy Awards and winning Best Adapted Screenplay for screenwriter Graham Moore, Morten Tyldum’s The Imitation Game and all the awards glory surrounding its release has resulted in the film being representative as a sort of cultural marker. In a year that saw the Academy heavily criticized for its noticeably white nominees across every major category, the inclusion of Tyldum as Best Director and the title amongst the Best Picture nominees came as a bit of a surprise considering the film’s very routine, unavoidably square structure as a well-intentioned, noble biopic. Marketed with urgent desperation as a film exploring the persecution of homosexuality while making a marked statement about the recuperation of the facts concerning the genius of Alan Turing, the accolades bestowed on this otherwise well mounted but incredibly milquetoast production is the political statement that the film simply does not have the courage to muster on its own.

Shut out at the BAFTAs, and nominated for eight Academy Awards and winning Best Adapted Screenplay for screenwriter Graham Moore, Morten Tyldum’s The Imitation Game and all the awards glory surrounding its release has resulted in the film being representative as a sort of cultural marker. In a year that saw the Academy heavily criticized for its noticeably white nominees across every major category, the inclusion of Tyldum as Best Director and the title amongst the Best Picture nominees came as a bit of a surprise considering the film’s very routine, unavoidably square structure as a well-intentioned, noble biopic. Marketed with urgent desperation as a film exploring the persecution of homosexuality while making a marked statement about the recuperation of the facts concerning the genius of Alan Turing, the accolades bestowed on this otherwise well mounted but incredibly milquetoast production is the political statement that the film simply does not have the courage to muster on its own.

Beginning in the winter of 1952, Detective Robert Nock (Rory Kinnear) investigates a burglary at the residence of mathematician and cryptologist Alan Turing (Benedict Cumberbatch). Turing ends up being suspiciously cagey about the matter, and Nock begins to look deeper into the incident, finding that the man was involved in some kind of government operation during World War II, leading him to believe Turing to be a spy. Only, another kind of scandal is brought to light, which reveals Turning to be gay, considered illegal at the time. Called in for questioning, Turing tells Nock a candid story about his involvement in breaking the Nazi’s Enigma code during the war. But war hero status was not enough to reverse the wheels of the law, which would find Turing (along with thousands of others) chemically castrated, leading him into a tailspin of depression that would end in his suicide in 1954.

As Turing, Cumberbatch gives a well-moderated performance as an incredibly anti-social type, written in such a way that it’s hard to determine if Turing is meant to be autistic or socially awkward due to having to keep his sexual orientation secret. We’re never allowed to see this version of Turing engage in any kind of feeling as an adult, instead we’re meant to believe he has an undying love for his first school-boy crush, which is juxtaposed unevenly throughout (basically we get memories anytime anyone utters the name Christopher, the name Turing coined for his massive code-breaking machine). While this may be true, and we don’t need to see Turing having full on sex (though obviously he was acting upon his desires), we get no notion of how Turing interprets his sexuality. He says he’s homosexual, several times, in fact. As his beard, (in a rather lovely performance) Keira Knightley even offers him a marriage of convenience despite the fact that he’s gay. We’re meant to understand that his declination is a noble move for her benefit, yet it also indicates a desire to retain his own agency.

As far as these types of films go, Moore’s screenplay is incredibly unexceptional, pouring on the heavy-handedness unabashedly (including his prized line “sometimes it is the people who no one imagines anything of who do the things no one can imagine, used three times), such as showing the juxtaposition of heterosexual flirtation between Matthew Goode and Tuppence Middleton. Cumberbatch (sometimes a bit stiff and even silly, such as when he caresses the cords coming out of his home made computer as if it were a loved one) and Knightley tend to supersede these limitations, though supporting players tend to feel a bit stock, with Mark Strong and Rory Kinnear underutilized, while Charles Dance gives a brittle and bitchy performance as Commander Denniston.

Disc Review:

Presented in Dolby Digital with Widescreen 2.39:1 aspect ratio, Oscar Faura’s handsomely photographed frames generally capture the sense of war torn England as a prolonged race against the clock transpires at Bletchley Park. Battlefield sequences look a bit generically set, likewise routine sequences of Britain’s denizens flowing underground during air raids. Alexandre Desplat’s score, though Oscar nominated, seems a belabored attempt to grant the film a sort of martyred nobility. Feature commentary from Tyldum and Moore is available, along with a few extra features.

The Making of The Imitation Game:

A twenty two minute featurette finds cast and crew interviews from Moore, Knightley, and Cumberbatch, along with pictures and facts pertaining to the real Alan Turing. Scholars discuss actual circumstances of the period.

Deleted Scenes:

Three minutes of cut footage are included, two separate scenes involving Rory Kinnear’s detective.

Q+A Highlights:

Thirty minutes of footage from a post-screening Q+A with Moore and from the 2014 Telluride Film Festival finds the screenwriter discussing his life long obsession with Turing, having wanted to write about the man since he was about fourteen or fifteen years of age, discussing the cult-like status a figure like Turing has amongs the computer crowd. Producer Teddy Schwarzman discusses the difficulty of getting a film like this made in Hollywood. Tyldum recalls how he came on board the project (he originally was supposed to direct Bastille Day, which fell apart at the time). Cumberbatch speaks of how he approached the role of man of whom there exists no actual recording of.

Final Thoughts:

In 2001, director Michael Apted directed a film called Enigma from a screenplay by Tom Stoppard, starring Dougray Scott and Kate Winslet. That film is a fictional account based on the WWII endeavors of Alan Turing, conveniently modified into a heterosexual hero. With Queen Elizabeth II’s pardon of Turing only two years prior in 2013, perhaps it was too much to expect from The Imitation Game to do much more than simply admit that yes, Alan Turing was an important man that was gay. Yet the horrific circumstances of his chemical castration and the very real realities of his life as a gay man are sidestepped by the faux thriller set-up of the film, a device that conveniently allows a heterosexual writer like Moore (who’s Oscar acceptance speech granted us insight into how his version of Turing lacks any on-screen interiority as a gay man) to touch upon the subject as a clichéd trope.

Like The Dallas Buyers Club before it, we’ve reached a platform where central gay characters can consistently court awards attention if retaining the mainstream demand to be presented in asexually, neutered formats. The elegiac use of the film’s title, then, can inadvertently be the game administered as a test as concerns this portrayal of Turing—by the final frames, we have a mere gasp of understanding what his life was like, a rough, nobly hewn composite from a perspective either too ignorant or too uneasy to deal with the realities of those historically treated as sexual criminals.

Film: ★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc: ★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆