Parallel Mothers: Diop Explores Monstrousness and Motherhood in Provocative Courtroom Drama

For her narrative feature debut Saint Omer, Alice Diop builds an agonizing and elegant duality around the salvation of a Medea, evoking the timeless antagonist of Euripedes’ Greek tragedy, where motherhood and monstrosity are inextricably, eternally linked. At its core, this is a stunning fly-on-the-wall melodrama filled with extended sequences of French courtroom deliberation as a Senegalese woman stands trial for the murder of her fifteen-month old daughter, but complex layers and an outsider’s perspective enhances a universal scope on the psychological warfare motherhood employs.

For her narrative feature debut Saint Omer, Alice Diop builds an agonizing and elegant duality around the salvation of a Medea, evoking the timeless antagonist of Euripedes’ Greek tragedy, where motherhood and monstrosity are inextricably, eternally linked. At its core, this is a stunning fly-on-the-wall melodrama filled with extended sequences of French courtroom deliberation as a Senegalese woman stands trial for the murder of her fifteen-month old daughter, but complex layers and an outsider’s perspective enhances a universal scope on the psychological warfare motherhood employs.

A formidably complex script from Diop, with the assistance of her editor Amrita David and Marie N’Diaye (White Material, 2009) is fleshed out by a handful of equally astute performances peeling away the inherent theatricality of the courtroom melodrama to present an exercise in raw, human emotion. Reminiscent of several titans of French language cinema, Diop transposes both a singular perspective and unique reinvention on a universal mythos.

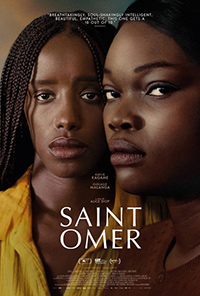

Rama (Kayije Kagame) is a noted author and lecturer who has chosen to explore the Medea myth through the examination of a young woman named Laurence Coly (Guslagie Malanga), a Senegalese immigrant woman currently standing trial for the murder of her infant daughter in the northern, incredibly conservative town of Saint Omer. It’s clear Rama is undergoing her own familial difficulties, the child of immigrants herself, though sharing an emotionally estranged relationship with her own mother. She’s in a committed relationship with Adrien (Thomas De Pourquery), but also has reasons for keeping him at a distance, partially because, as a white man, he’s an outsider in more ways than one. Rama shows up to Laurence’s trial as jury selection begins, and an emotionally draining process ensues as the woman is questioned in painstaking detail about the life circumstances which brought her to where she is, mothering in secret a child with a white Frenchman decades older and still married to his first wife. The baffled court attempts to rationalize her claims of sorcery having bewitched her to commit a heinous crime.

Like the railway as the connective apparatus of her 2021 documentary, We, the courtroom provides the nexus where Diop recontextualizes the white male gaze through Rama, where an ambiguity begins to occur between observer and subject. What Rama sees, and what women see (one glance at Rama and Laurence’s mother can sense she’s pregnant), defines an interpretation of Laurence’s unthinkable act. Rama’s ambivalence towards motherhood itself, due to her own unhappily complex relationship with her own, becomes a confrontation when the two women share a brief glance in court. It’s Laurence’s only hint at a smile, but for Rama it’s as if she’s been staring into the abyss, and it’s now staring right back into her.

Riding a line between the observational aesthetic of the subject and the inherent power of narrative storytelling, the power is in representation. Medea, a sorceress, is a tragic figure whose horrific infanticide is understood as an erasure of future, of connection. Rama, and by default Diop, aligns Laurence directly with how Pasolini humanized the infamous witch. We see a twice removed visualization of infanticide as Rama watches the humanizing affection and tenderness engaged by Maria Callas from the Pasolini film. And it’s what Diop is accomplishing with Laurence, a composite of Fabienne Kabou. Much is made of how Laurence speaks in the ether of the trial’s press coverage (if you close your eyes, you might picture Lea Seydoux, exploring how speech dialects generate culturally conditioned discordant conversations), and the inherent ridiculousness of her articulation arrives full force when Rama’s publisher comments on it. Referring to Laurence, he crows about her intellect and speech pattern. “She’s educated,” Rama curtly replies, the unfathomable reality ignored in the understanding of how a Black immigrant woman might sound, tied to stereotypes through her heritage and automatically estranged from it thanks to her education. Saint Omer is about a woman displaced, and like Medea, stamps out a future representing a doomed collision of power and weakness. Laurence’s Jason of the Argonauts is France itself.

The captivating Kayije Kagame floats into the background of Saint Omer, a performance based on response and reaction which grows intensely, like the life within her she hasn’t chosen to acknowledge yet. If she’s the silent witness, she’s matched by an equally loquacious performance by Guslagie Malanga, and though this is a composite not defined by significant outbursts, it recalls another ‘woman defending her life’ courtroom drama, Henri-Georges Clouzot’s La Verite (1961), with Brigitte Bardot as a woman whose entire personal life is dissected for a jury determining her guilt over the death of a lover.

Laurence’s wardrobe allows her to blend in with the wood paneling of the witness stand as Claire Mathon’s lengthy, static shots enhance her invisible sublimation in the very fabric of her environment, surfacing only to be handed down a judgment. Diop opens the film with Rama in a position of power, lecturing to students assigned to examine the works of Marguerite Duras in conjunction with the demeaning treatment of women post WWII, hair shaved as a way to denigrate, to shame. The nature of the lecture regards repositioning these experiences through the lens of Duras, who grants them a heroic power unattainable in the public moment, as well as the shared memory of those who witness their trauma.

Saint Omer is about two women, who share significant similarities, a system of silent exchange transpiring between them, but both giving something back taken away. It’s a narrative retreating violently into the arms of motherhood and its overwhelming, devouring nature. Looming large is the eternal mother symbol of water, which can both hide and reveal, but in this example as always ‘the sea will tell.’

Saint Omer builds to a quiet crescendo of a closing statement, presented in earnest close-up from a defense attorney (Aurelia Petit) who, heretofore, was merely a sympathetic accent. And yet, it is one of the most eloquent examples of its kind, relayed firmly, quietly, and intensely as she makes a moving hypothesis about monsters and motherhood.

Reviewed on September 7th at the 2022 Venice Film Festival – In Competition. 122 Mins

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆