Dole Days: Arnold Flutters About with Strange Bedfellows

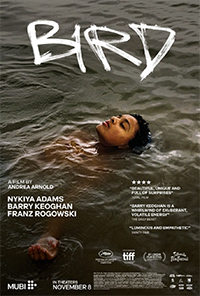

There’s certainly a definable emotional core in Andrea Arnold’s fifth narrative feature, Bird, but the ideas and themes tying it all together are about as wispy and freewheeling as scattered feathers drifting along the course of a gently idling wind. Once again mixing anthropomorphic inspired motifs with working class realities, Arnold’s new marriage of social miserabilism and magical realism sadly feels a bit exploitative as it rushes through thinly drawn characters and connections before gliding into a pat, feel-good resolution. Whether due to methods of improvisation without a clearly defined script or a rushed edit to make the demands of its world premiere, Arnold’s latest is something of a disappointment, playing as it does so fiercely into the eternally forgiving arena of the sentimental.

There’s certainly a definable emotional core in Andrea Arnold’s fifth narrative feature, Bird, but the ideas and themes tying it all together are about as wispy and freewheeling as scattered feathers drifting along the course of a gently idling wind. Once again mixing anthropomorphic inspired motifs with working class realities, Arnold’s new marriage of social miserabilism and magical realism sadly feels a bit exploitative as it rushes through thinly drawn characters and connections before gliding into a pat, feel-good resolution. Whether due to methods of improvisation without a clearly defined script or a rushed edit to make the demands of its world premiere, Arnold’s latest is something of a disappointment, playing as it does so fiercely into the eternally forgiving arena of the sentimental.

Bailey (Nykiya Adams) is a twelve-year-old from northern Kent living with her father, Bug (Barry Keoghen) and older half-brother Hunter (Jason Buda). She’s dismayed to learn her father plans to marry his girlfriend of three months, Kayleigh (Frankie Box) the following weekend, and Bailey is expected to be a bridesmaid (who will all be wearing purple spandex catsuits). Bailey refuses, having her brother’s girlfriend cut her hair as a symbol of her rebellion. One evening, she follows her brother’s posse during one of their now customary raids to maim a neighborhood abuser, later falling asleep in an open field. She awakens to see a curious fellow approaching named Bird (Franz Rogowski), looking for a housing project which happens to be next door to hers. Bird is in search of his parents, as he was reared there long ago. Vowing to assist him by introducing him to her mother, who used to live in that building, Bird waits on the rooftop for Bailey to fetch him. What Bailey finds at her mother’s alarms her, as it seems to have turned into a flophouse where she has three younger half-siblings living in fear of her new boyfriend, the abusive Skate (James Nelson-Joyce). In response, Bailey puts out a request to Hunter’s friends to assist. But she finds a much more beneficial presence in the mysterious Bird.

Much like Fish Tank (2009) and particularly American Honey (2016), Arnold returns to the impossibly dysfunctional realm of a working class domestic sphere through the eyes of an adolescent young woman. As Bailey, newcomer Nykiya Adams gives an internalized performance as an unformed personality still deciding who she wants to be—only without any real opportunity to do so thanks to the constantly shifting chaos of the questionable adults in charge and peers fixated on rebellion and violence. In some ways, this is a far cry from the impassioned Sasha Lane of Arnold’s previous film, but we learn little of Bailey beyond the necessity of reacting to her environment. Ultimately, the real problem with Bird is how low the dramatic stakes are, a collision of dangerous events feeling coincidental and fortuitous while an impending wedding hangs in the air to signify a coming denouement.

As the titular character, Franz Rogowski is on hand as a magical vagabond, who rides an interesting line between seeming crazed and innocent as he twirls around in a field with a skirt and behaves much like his avian namesakes, perched atop a building waiting for an impetus to move on. His characterization is like a mix of various mentally ill characters obsessed with being winged creatures, like the Vietnam veteran played by Matthew Modine in Alan Parker’s Birdy (1984), while Natalie Portman’s troubled transfiguration in Black Swan (2010) also comes to mind. He’s also the weakest part of the film, a narrative convenience for Bailey’s current miseries, churning the reality of British working class desolation a la Loach or Terence Davies into a low stakes YA escapade. Arnold’s penchant for pronounced soundtrack selections feels more like an escapist crutch this time around, injecting melancholy pop tunes both diegetically and non which never quite seem to match (and certainly not enhance) the visuals.

Rounding out the principals is Barry Keoghan, a loving but somewhat detached father presumably pushing thirty (and about to become a grandfather) who has decided to marry his latest lady love and pay for the wedding by selling hallucinogenic slime he can coax out of a large toad (which plays as randomly as it sounds). For whatever reason, Arnold felt it necessary to include a wink-wink nod to Keoghan’s nude dancing sequence to “Murder on the Dance Floor” in the parting shot of Emerald Fennell’s Saltburn (2023). We learn little else about Bug other than characterization dictated by his name underlined by the myriad of insects tattooed all over his body.

Despite its flaws, Arnold does indeed have a knack for capturing struggles and sentiments of people in a certain time and place, and decades from now, Bird might feel rightly like a predecessor of underground British Neo-realism classics before her, such as Franco Rosso’s Babylon (1980) or Isaac Julien’s Young Soul Rebels (1991), as representative of Britain’s continually shifting class struggles. But unfortunately, Arnold’s narrative doesn’t rightly earn the emotional payoff it employs.

Reviewed on May 17th at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival – Competition. 119 Mins.

★★/☆☆☆☆☆