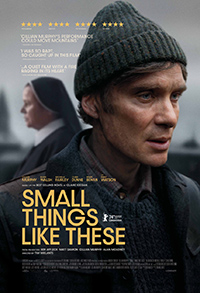

All the Small Things: Mielants Mines the Evils of Complicity

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” The oft cited quote from Edmund Burke is the ultimate essence of Small Things Like These, the latest from Belgian director Tim Mielants. Adapted from the 2021 novella by Claire Keegan (who also wrote The Quiet Girl), it’s a subtle exploration of the infamous Magdalene Laundries, torturous institutions run by the Roman Catholic Church intended to house ‘fallen women.’ While many films have explored the dreadful details of this culturally sanctioned terror, Mielants expounds upon Keegan’s prose to highlight the communal complicity which allowed this institutionalization to prosper. Cillian Murphy leads an understated cast as a man forced to confront the ghosts of his own past, while weighing the consequences of being part of the problem or doing the right thing.

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” The oft cited quote from Edmund Burke is the ultimate essence of Small Things Like These, the latest from Belgian director Tim Mielants. Adapted from the 2021 novella by Claire Keegan (who also wrote The Quiet Girl), it’s a subtle exploration of the infamous Magdalene Laundries, torturous institutions run by the Roman Catholic Church intended to house ‘fallen women.’ While many films have explored the dreadful details of this culturally sanctioned terror, Mielants expounds upon Keegan’s prose to highlight the communal complicity which allowed this institutionalization to prosper. Cillian Murphy leads an understated cast as a man forced to confront the ghosts of his own past, while weighing the consequences of being part of the problem or doing the right thing.

Coal merchant Bill Furlough (Murphy) is an integral part of the community in his small town in County Wexford, Ireland. He shares a loving home with wife Eileen (Eileen Walsh) and their five daughters. He’s a sensitive soul, attuned to the miseries of those around him, much to Eileen’s chagrin. As Christmas nears, Bill happens upon witnessing a young woman being forced into the local convent doors against her will, a place where many young women are kept who have stumbled into various sorts of social impropriety. Within the convent run by the stone-faced Sister Mary (Emily Watson), the young women are kept as slave laborers for endless laundry services, often pregnant and working under harsh conditions. Entering the convent to deliver an invoice, he’s confronted by the terror stricken woman begging him for help. This moment triggers traumatic memories from Bill’s own past, whose unwed mother was taken in by a kindly wealthy woman, Mrs. Wilson (Michelle Fairley). As we flashback to the tragic events of one particular Christmas and puzzle together secrets from his past, Bill happens to find the young woman, Sarah, locked in the coal shed. As he’s urged by his wife and other community members to simply look the other way, Bill finds he cannot.

Ultimately, Small Things Like These is overtly a dreary Christmas story, the specter of Charles Dickens lurking in the subtexts to haunt the ‘soft hearted’ coal merchant. Set in 1985, the actual period is barely addressed, save for The Human League’s “Don’t You Want Me” playing in the background during one of the film’s more overt conversations about Bill Furlong’s ‘meddling.’ Eventually, the unseemly secrets of Bill’s own origins take shape, much like the complicated puzzle he’d asked Santa for as a child but never received. In essence, actual benevolence is found anywhere but inside the sterile confines of the convent, run by a two-faced mother superior played with icy deadliness by Emily Watson. It’s perhaps this bit of casting which seems most alarming in the film, the usually cherubic Watson recalling Louise Fletcher’s villainous Nurse Ratched in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975).

Murphy is quite moving as a steadfast everyman, with a wife and five daughters of his own to support. His wife’s response to his concern is logical, a viewpoint shared by the community at large. “Worry about your own family.” The film’s most effective moment arrives in a barbershop, where another memory is triggered, and perhaps a plan of action is born. Ultimately, the most harrowing aspect of Small Things Like These is the reality of how only a person traumatized by a system can be the rebellious impetus to take a stand against it.

The ultimate irony is to have these events take place during the celebration of Christ’s birthday, wherein his most ‘devoted’ acolytes are anything but Christ-like. Subversive in these critiques and ultimately a portrait of what it really means to be humane, it’s a far cry from the anguishing bombast of Stephen Frears’ affecting Philomena (2013), or the more comprehensively agonizing The Magdalene Sisters (2002) from Peter Mullan. The end credits pay tribute to these women housed in these institutions from 1926 to 1996, but the practice of the Catholic Church and its cure for untoward women stretches back even further. Though Mielants keeps this a quiet, even keeled drama, it’s another reminder of organized religion’s underbelly and the penalties reserved for those unwilling to be controlled by its mendacity.

Reviewed on February 15th at the 2024 Berlin International Film Festival – Main Competition section – OPENING FILM. 96 mins.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆