Betty’s Blue: Chabrol’s Compelling Character Study of Victimhood and Agency

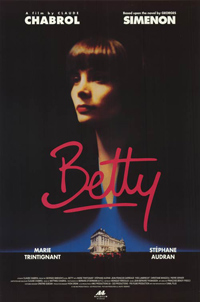

Claude Chabrol, dubbed the Alfred Hitchcock after rising out of the Nouvelle Vague, began his lucrative 1990s on a stunningly sour note with two films starring Andrew McCarthy, one a bizarre Dr. Mabuse remake, Dr. M. (released on VHS as Club Extinction), the other a Henry Miller adaptation, Quiet Days in Clichy. A year later, he would direct what stands as the most definitive cinematic version of Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1991) to date before settling in on a deliciously offbeat character study with Betty (1992), a provocative character portrait starring Marie Trintignant, the daughter of famed actor Jean-Louis Trintignant and director Nadine Trintignant, and who was tragically killed following a violent altercation with rocker boyfriend Bertrand Cantat (of band Noir Desir) in 2003. An adaptation of famed French noir author Georges Simenon, it’s a deliberately paced portrait of a fallen woman, forced out of her bourgeois social circle thanks to her sexual proclivities resulting in a promiscuous reputation. Following a devastating turn of events, a kindly older woman assists her as we learn via intermingling and jumbled flashback the circumstances which have led to her ultimate undoing as a woman who has agreed to sell her children to her husband’s family in order to maintain her dignity.

Claude Chabrol, dubbed the Alfred Hitchcock after rising out of the Nouvelle Vague, began his lucrative 1990s on a stunningly sour note with two films starring Andrew McCarthy, one a bizarre Dr. Mabuse remake, Dr. M. (released on VHS as Club Extinction), the other a Henry Miller adaptation, Quiet Days in Clichy. A year later, he would direct what stands as the most definitive cinematic version of Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (1991) to date before settling in on a deliciously offbeat character study with Betty (1992), a provocative character portrait starring Marie Trintignant, the daughter of famed actor Jean-Louis Trintignant and director Nadine Trintignant, and who was tragically killed following a violent altercation with rocker boyfriend Bertrand Cantat (of band Noir Desir) in 2003. An adaptation of famed French noir author Georges Simenon, it’s a deliberately paced portrait of a fallen woman, forced out of her bourgeois social circle thanks to her sexual proclivities resulting in a promiscuous reputation. Following a devastating turn of events, a kindly older woman assists her as we learn via intermingling and jumbled flashback the circumstances which have led to her ultimate undoing as a woman who has agreed to sell her children to her husband’s family in order to maintain her dignity.

Drunk and alone, the beautiful and distraught Betty (Marie Trintigant) chainsmokes through a boozy stupor one rainy Parisian night until a leering gentleman, claiming to be a doctor, picks her up and takes her to a seedy dive bar in Versailles. The man is a known drug addict, and Betty is rescued by an empathetic bar patron, Laure (Stephane Audran), who owns a hotel and puts the young woman up for the night. Over the next several days, we learn why Betty has ended up so seemingly destitute. After caught cheating on her husband, her bourgeois extended family demands she sign over custody of the children in exchange for a economic stability and leave both them and the home immediately. Emotionally wounded, Betty sets her sights on Laure’s lover, Mario (Jean-Francois Garreaud) while she shares memories of her past sexual experiences.

In many ways, Simenon’s Betty recalls the sullen and embittered heroine of Octave Mirabeau’s The Diary of a Chambermaid (thrice adapted for film by renowned auteurs, including Renoir, Bunuel, and most recently, Benoit Jacquot), a woman whose beauty has the ability to usurp her assigned social order, but whose cynical personality and problematic conditioning perpetrate of her own downfall. Chabrol’s flashback structure also recalls the troubled Joe at the center of Lars Von Trier’s epic sex addition odyssey, Nymphomaniac (2013). Like those films, Betty isn’t so much concerned about narrative as it is characterization (the name itself carries a particular cinematic heft in French cinema, from Beinex’s Betty Blue, Miller’s Alias Betty, and even the con-artist played by Huppert in Chabrol’s The Swindle), and centering this scenario is not only Trintignant’s emotionally paralyzed, helplessly promiscuous titular character, but Stephane Audran’s mysterious Laure.

As a hotelier who wanders aimlessly throughout a life of transitory experiences (their chance encounter in a bar called “The Hole” couldn’t be more fitting), Audran actually balances a more complex performance as a woman whose motivations are almost inscrutable (it’s also interesting to note Audran not only used to be married to Chabrol, but also her co-star’s father, Jean-Louis Trintignant, which rather heightens her sense of a makeshift mother). Clearly sympathetic towards Betty, she often talks over the woman, an attempt to command the situation at all times, a complicated battle of personality and will. Jean-Francois Garreaud is the pawn in their strange scheme, their copulation flaunted in Betty’s, and the eventual prize which allows one to succeed and the other to fail. But at what, exactly?

Flashbacks of Betty’s sexual awareness and her understanding of a woman’s experience in heterosexual congress are brief but succinct in underlining her character’s faults, at least as the parameters dictated by the social ogliarchy she’s ascended to by marrying into the Etamble clan against her better judgment. Another important female figure here is Madame Etamble, played with all the clichéd vicissitudes of manipulative matriarchs by Christiane Minazzoli in a role which would later be echoed in 2007’s The Girl Cut in Two with a madame played by Caroline Silhol, another of Chabrol’s more tawdry exercises examining portraits of liberated female sexuality. Intriguing and potently administered, there are bounteous compelling elements both in and outside Betty’s frames, and should have more of a renowned reputation than it does from Chabrol’s later period.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆