Stranger in a Strange Land: Antoniak Explores the Black and White of the Refugee Crisis

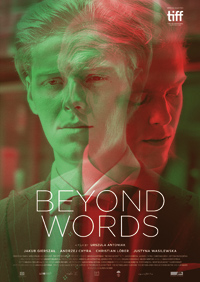

The ongoing refugee crisis provides the framework of Urszula Antoniak’s fourth feature, Beyond Words, a black and white drama of estranged family members uniting in a deliberation on origins and identity, and how these concepts don’t quite wholly define lives. Often exploring the sometimes-innate loneliness of the human experience, including her 2009 breakout debut Nothing Personal (which nabbed Best First Feature of or Locarno), her latest examination again revolves around two disparate personalities who become enamored with one another.

The ongoing refugee crisis provides the framework of Urszula Antoniak’s fourth feature, Beyond Words, a black and white drama of estranged family members uniting in a deliberation on origins and identity, and how these concepts don’t quite wholly define lives. Often exploring the sometimes-innate loneliness of the human experience, including her 2009 breakout debut Nothing Personal (which nabbed Best First Feature of or Locarno), her latest examination again revolves around two disparate personalities who become enamored with one another.

This time around, Antoniak not only displaces her lens within the confines of Berlin, but focuses on two male figures, a successful refugee lawyer who suddenly meets the father he always thought was dead just as he’s been tasked with the defense of a client he has no interest in representing.

Polish-born Berlin based lawyer Michael (Jakub Gierszal) is troubled when his German boss and friend (Christian Lober) tasks him with handling the refugee-status case of a black poet, a man who doesn’t wish to present his claim as a foreigner. Realizing the poet’s defense may be heightened were it to be administered by another recognized immigrant, Michael attempts to distance himself, believing he has assimilated into a culture he now believes he has ownership of. But Michael’s perceptions are thrown off balance when his father Stanislaw (Andrzej Chyra) suddenly appears in his life, a man he had long thought dead. As the two men attempt to reconnect over an awkward weekend, Michael’s perception of himself and the world around them becomes a tad discombobulated.

“Who has the right to decide where someone else lives?” Michael muses early on in Beyond Words, after meeting with a potential client who remains tight-lipped to his own detriment. Callously, he declines the case, supposing he’s completed the requisite work to assume a German identity. His blunt boss reminds him, however, of his enduring status as an outsider, but adds, “Who wants to be German?” Antoniak’s psychological profiling of Michael’s self-loathing is as obvious as Lennert Hillege’s gorgeous, velvety cinematography is metaphorical—boiled down, there’s a black and a white part of the matter, and Michael’s whiteness allows him, at least superficially, the ability to assimilate across Euro cultures in ways the black poet, who represents a stark contrast, does not.

Poland, the largest of the former communist bloc countries, is an interesting identity considering the country has no immigration policy. In an effort to retain their ‘culture,’ one is either born a Polish citizen or is not, and there is no in-between. Berlin, currently one of the most socially progressive cities in the world is another matter—and yet, belongs to a German culture historically at odds with the atrocious treatment of Poland during WWII, the essence of which underlines some telling sequences between Stanislaw and Michael’s oblivious boss. “There are many stories there,” offers the drifting patriarch, a barb in response to cutting observations of his son, who is told “you’re a totally different person when you speak Polish.” Stanislaw attempts to bring his son back to his roots, trying to force a liaison with a young Polish woman (Justyna Wasilewska) after a bonding session at the strip club.

In several ways, Antoniak’s juxtaposed cultures in pristine black and white recalls Francois Ozon’s recent Frantz, which explores the raw emotions between France and Germany post WWII. Time, or visual representations of it, are a visual motif here, as evidenced by several shots of clocks, as well as the only gift Stanislaw can think to bestow on his son, a vintage watch.

Antoniak is the latest prolific Pole to utilize the talents of Andrzej Chyra, who starred in the late Andrzej Wajda’s Katyn (2007) as well as Malgorzata Szumowska’s masterful In the Name Of… (2013). In Beyond Words, he is merely the dramatic catalyst for Michael’s identity crisis, a crusty enigma who cites a malignant illness as the rationale for seeking out his son and requesting cash to finance his last hurrah. He’s a magnetic foil for the youthful Gierszal (who could easily stand in as a Skarsgard sibling), playing a character whose essence is perfectly explained in his early statement, “I don’t feel anything.”

Antoniak attempts to grant him salvation when he stumbles into a den of what we assume to be immigrants in an underground bar, playing pool and cards, remarking on the stupor of the displaced whiteness of Michael. The sequences don’t exactly have the intended effect of epiphany, but instead underscores the troubling reality of Beyond Words, which seems mostly to be dealing with white fears in black spaces, or at least the fear of existing as a minority in a world of less distinctly Euro environs.

As an exercise in significant deliberation, Beyond Words is a lush cinematic exchange, but as a meaningful melodrama about estrangement and human interaction, there’s an advisory quality quelling its emotional components. But we all have to eat vegetables sometimes.

Reviewed on September 8th at the 2017 Toronto International Film Festival – Contemporary World Cinema Programme. 85 Mins.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆