Chef Boyardee: Wells Fails with Filmmaking Recipe

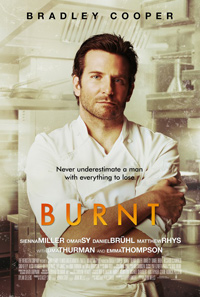

For his third film outing, director John Wells delves into the catty universe of high-end cuisine with Burnt (formerly titled Adam Jones for its lead character) with the same square generalities formulating the emotionless energy of previous dramas August: Osage County and The Company Men. Bradley Cooper once again plays a smug playboy, one of those confused personalities charged with simultaneous duties as narcissistic tyrant and charismatic romantic lead.

For his third film outing, director John Wells delves into the catty universe of high-end cuisine with Burnt (formerly titled Adam Jones for its lead character) with the same square generalities formulating the emotionless energy of previous dramas August: Osage County and The Company Men. Bradley Cooper once again plays a smug playboy, one of those confused personalities charged with simultaneous duties as narcissistic tyrant and charismatic romantic lead.

Attempting to extol the high-stakes wheeling and dealing of the fine-dining universe, it’s a film professing to depict the elegance and privilege of a specific scene but couldn’t be any more thanklessly banal. Much like another Bradley Cooper vehicle, the literary minded The Words (2012), the subject matter is sidelined by standard issue formulaic tropes, satisfying every conceivable audience expectation.

A once revered two-star Michelin rated chef, Adam Jones (Cooper), sucks down his millionth oyster working in New Orleans and announces his penance for past sins to be over. A brief introduction to an infamous past, involving drug abuse and sabotaging colleague’s restaurants is revealed as he makes his way to London with the aim of taking over his old mentor’s haunt, now run by his son, second rate chef Tony (Daniel Bruhl), a man who still harbors a burning crush for Jones. Tony agrees his restaurant is in need of improvement, especially after Jones dances a predatory food critic (Uma Thurman) in for a surprise visit. But in order to secure financial backing, Jones must agree to undergo weekly visits with a therapist (Emma Thompson), who also tests him for the consumption of illegal substances. Now, Jones assembles his finest team, including a past frenemy (Omar Sy) and an incredibly talented young sous chef (Sienna Miller) who loathes him.

You can add Burnt to the stack of screenwriter Steven Knight’s deflated efforts, like Seventh Son or The 100 Foot Journey, another wildly mundane effort from the scribe also behind innovations like Stephen Frears’ Dirty Pretty Things (2002) or his own directorial effort, Locke (2013). There are moments suggesting a more daring venture considering the problematic background of its lead character, an ex-heroin junkie whose sketchy past must have been downplayed considerably so the film would appeal to The Weinstein Company’s bread and butter art-house audiences who prize the rigidity of prestige over the messiness of realistic tendencies.

Despite its demure characterization of a brilliant chef reestablishing himself following the conquering of past demons, Bradley Cooper is still woefully miscast. It’s not that Cooper isn’t able to channel the self-entitlement of an injured genius, but he simply isn’t rough enough around the edges. This role calls for someone severely frayed around the edges, and had this been made in the early 90s, it would have been a marvelous vehicle for someone like Steve Railsback. Instead, we’re treated to heavy doses of improbability, of course involving unlikely romance with an undiscovered talent of equal brilliance played by none other than a single mother who looks like Sienna Miller. Following a moment of show-stopping abusive violence, including an uncomfortably physical altercation, we’re still meant to believe Jones’ rough edges have been sanded down to permit his assumption of cuddly family man, but it’s at the cost of presenting its lead female character as an absolute moron. What mother in their right mind would allow her child to be subjected to a man as unhinged as Cooper’s character proves himself to be?

Rob Simonsen’s leading score informs us of how we’re supposed to feel at every possible juncture, while several notable names in the supporting cast, like Omar Sy, Emma Thompson and Daniel Bruhl are too broadly drawn to register as realistic people.

The behind the scenes carnage of dueling elitist chefs has recently discovered resurgence, with sub-par items like Daniel Cohen’s 2012 film Le Chef arriving from France and Roger Gaul’s 2013 Spanish co-production Tasting Menu trickling through cinemas in recent years. The Weinsteins are perhaps hoping for the same crowd attracted to their acquisition Haute Cuisine (2012) an elegant rendering of Francois Mitterand’s private chef played by Catherine Frot. But Burnt is about as exciting as a Hamburger Helper adorned with Saltines, and doubly aggravating for assuming built-in-empathy for a privileged subset of folks far removed from day-to-day realities. One sequence of truth telling involves Cooper sharing wisdom with Miller in a fast food chain, itself a microcosm of an infinitely more interesting topic.

With Cooper’s arms-crossed visage looming over billboards across Los Angeles this season, from the haute couture of Beverly Hills to the less cherished neighborhoods of Inglewood, it’s uncertain who exactly this film is being marketed to and why they’d be interested in these spoiled monsters who take everything for granted as they reside in a fantasy world of endless opportunity.

★★/☆☆☆☆☆