Night Boos: Hochhäusler Bungles Black Market Crime Thriller

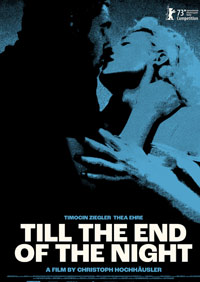

Blending fatal romanticism and B-movie genre tropes, it’s not difficult to see where a certain Fassbinder sensibility creeps into Till the End of the Night, the sixth film from Berlin School filmmaker Christoph Hochhäusler, and his first after nearly a decade away from the director’s seat. But the specter of Fassbinder appears only in the film’s glorious poster art and the woozy heartbreak of a well curated soundtrack.

Blending fatal romanticism and B-movie genre tropes, it’s not difficult to see where a certain Fassbinder sensibility creeps into Till the End of the Night, the sixth film from Berlin School filmmaker Christoph Hochhäusler, and his first after nearly a decade away from the director’s seat. But the specter of Fassbinder appears only in the film’s glorious poster art and the woozy heartbreak of a well curated soundtrack.

The set-up sounds fantastically promising when a trans woman recently released from incarceration is forced to assist in an undercover operation to arrest a digital drug dealer who runs a booming black market website. A myriad of personal complications ensue, and both the stakes and the concept are ripe for exploration. But somehow, Florian Plumeyer’s tediously inept script sabotages not only these themes but also what could have been a striking quartet of viciously unhappy but needy humans.

Leni (Thea Ehre) has recently been released from prison on drug charges, returning home to a surprise party orchestrated by her boyfriend, Robert (Timocin Ziegler). But once the party ends, it appears this has all been a charade. Robert and Leni were once lovers, back before she began her gender transition. Now, things have changed between them. Robert is an undercover cop trying to nab Victor Arth (Michael Sideris), a once famous DJ who owns a happening nightclub called Midnite. But Victor also runs a website for a popular black market network which mails drugs with innocuous items to elude the police. Victor used to employ Leni as a sound engineer at his club, so she received an early release to assist Robert in wheedling her way into Victor’s good graces. Things don’t go quite as planned.

Ironically, the only whiff of authenticity arrives courtesy of Thea Ehre’s performance, if only because she’s actually trans. Much like the way Robert and Leni are only able to successfully sell their sham romance to Victor because they lean into the genuine distress inherent in their relationship, Ehre’s Leni succeeds as a character because it’s closer to a reality.

Unfortunately no one else comes close to successfully playing any aspect of their hobbled characters, which makes the entire affair feel like cheap playacting, crumbling the film’s stakes before we can ever attempt to scale them. A whole lot of distracting details surely make this film feel offensive to both law enforcement and passive drug dealers, for Robert and Victor are comically inept. Questions are sparked immediately, such as why Leni would be forced to wear an ankle bracelet outside of her conning shifts. Initial intrigue suggests Leni isn’t in the right headspace to lie believably and can’t bother to remember pertinent details about the false cover with Robert, most likely because this is complicated by the very real relationship she did have with him. Another compromising factor is her gender transition, something she paid for by selling drugs.

Why Robert’s unnecessarily combative boss would allow him to lead such an important investigation despite his known addiction issues and the strained relationship with Leni is another matter entirely. There are ways all of these details could have been ironed out in some scrubbing of the script, but Hochhäusler perhaps mistakes this shaggy sensibility for grit. But there’s none. It also plays too vaguely with Leni’s likely psychological duress regarding Robert’s treatment.

Marlene Dietrich creeps up to lull us back into the complicated wavelengths of Leni and Robert’s past, but music is only another superficial flourish in mining their discord, which should have been the focal point through all of this. Is Robert’s arrangement for Leni born of love or punishment? Does Leni still love Robert? Because neither of them want to address Leni’s transition head-on, as Robert seems to prefer the company of cis men. These could have been some compelling elements complicating their mission, especially as compared to Victor’s relationship to a girlfriend who works as a saleswoman in a clothing store with whom he’s agreed to take dance lessons with as therapy. A break-up scene utilizing a box of chocolates might be one of the film’s stupidest moments thanks to dialogue which feels forced and insincere. Maybe life is like a box of chocolates worthy of being tossed out a moving car window, but this is a film where we want to follow right behind it.

DP Reinhold Vorschneider’s (The Dreamed Path, 2016; Hochhäusler’s The Lies of the Victors, 2014) provides some genre themed swagger, but it ultimately feels like a false sense of moving things along, roving through frames which eventually feel like the experience of drinking too much and getting the spins. Unfortunately, Till the End of the Night never manages to break the dawn.

Reviewed on February 24th at the 2023 Berlin International Film Festival – Competition. 123 mins.

★/☆☆☆☆☆