Night Nurse: Faith Finds the Night the Lights Went Out on the Patriarchy in Moody Debt

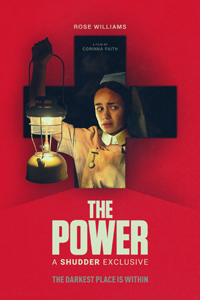

Director Corinna Faith makes fine use of period and metaphor in her directorial debut The Power, which feels most persuasive when utilizing its greatest potential of fearing what can’t be seen—especially when there are a myriad of insidious humans lurking in the shadows of a 1970s era hospital who happen to be colleagues and not patients.

Director Corinna Faith makes fine use of period and metaphor in her directorial debut The Power, which feels most persuasive when utilizing its greatest potential of fearing what can’t be seen—especially when there are a myriad of insidious humans lurking in the shadows of a 1970s era hospital who happen to be colleagues and not patients.

Set during a specific period in 1974, when the conservative Heath ministry dictated the Three-Day Week, whereby commercial use of electricity was restricted to conserve electricity, a passive young nurse finds herself forced to work a night shift in an unsavory East London hospital. Her presence invokes a restless spirit, and while Faith’s third act formulation feels rote, the journey to its predictable ending concocts formidable unease and frustration.

In East London, January 1974, Val (Rose Williams) has just accepted a position as a nurse in an unfashionable hospital. Having grown up as an orphan in a convent, Val is interested in giving back to the community and exploring the correlation between medicine and poverty. The Matron (Diveen Henry) is hardly impressed, vowing she’s quick to fire staff who aren’t a good fit. It just so happens the major tasking of the day is to move all the patients due to newly mandated electrical blackouts. Interested in pediatrics, Val takes an immediate liking to Saba (Shakira Rahman) and she bonds with the handsome young Dr. Franklyn (Charlie Carrick) over her care, which angers the Matron, who advised Val not to address the doctors. As punishment, Val is lassoed into working a night shift. Once the lights go out, and only select areas are lit by the generator, Val begins to hear and experience a supernatural presence belonging to a young girl no one wants to admit was once a patient besides Saba.

Like a mix of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) and Halloween II (1981), the night shift in a desolate hospital, populated by unhappy staff members desensitized to their wards thanks to their own dissatisfaction in the economic hierarchy, hardly breeds potential for joy. As per usual, the head Matron (here played by an imperious but understandably terse Diveen Henry, who describes the populace dependent upon the hospital’s services as people who ‘live like animals’), like Mother Superiors, brothel Madams and various governesses throughout literature, occupies a tenuous position of power, and all the pricklier for the thankless instability this offers.

Like Nurse Rachet, Nurse Bucket or Julia Blake’s Matron Cassidy in the cult classic Patrick (1978), Henry’s Matron is more foe than friend to Val. Of course, Faith eventually proves those who show their true colors are ultimately easier to handle, from the Matron to a handsy janitor and a groundskeeper who seems prone to sexual assault of the night nurses. The reveal of the actual antagonist, however, should feel more like a ‘fallen idol’ moment than it does, and one wishes there was just a titch more connective tissue to showcase the change of heart afforded some other characters.

Eventually, the supernatural elements in The Power take the forefront, and Faith’s film eventually plays itself out to the logical conclusions. However, one wishes the prominence of East London 1974, the politics, and governmental policies of the period, had felt just a little more enriching to the material. As it stands, Faith injects some wonderful metaphorical prowess in paralleling the literal black outs for the conservation of ‘power’ to the rippling effects of the narrative and hypothetical disruptions to power of the patriarchy and the entrenched hierarchy of something like the medical field, from doctor, to matron, to the pool of nurses forced to scrabble amongst themselves like crabs in a bucket.

Laura Bellingham, who lensed Romola Garai’s effectively creepy 2020 debut Amulet, proves to be a master at mood and restraint, and The Power’s visual palette serves a delicious exercise to watch at night with all the lights off.

Rose Williams (who played a young version of the Jennifer Ehle character in Terrence Davies’ 2016 masterpiece A Quiet Passion) is effectively empathetic, even if her traumatic backstory demands more attention (though this speaks to the film’s overall effectiveness in wanting more and not less). Like an aesthetic mixture of Brie Larson and Alicia Vikander, she’s a likeable leading lady. “There’s always something trying to control you in a place like this,” says Comfort (Gbemisola Ikumelo, portraying a fellow nurse caught between a rock and a hard place), is a phrase which reverberates throughout. Despite a karmically appropriate finale in The Power, it’s a reality Val and women across all intersections, cultures and periods still contend with.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆