Category is The Realness: Lessovitz Isn’t Strictly Ballroom in Star Crossed Romance

To acknowledge the formidable, everlasting impact of Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary Paris is Burning, itself a successor to the recently restored 1968 doc The Queen, part of the conversation must include acknowledgement of appropriation. The privilege of the cultural gatekeeper, as in who gets to convey what stories, etc., has defined our understanding of others through cinematic representation. Obviously, this includes our established, well-hewn conditioning of whiteness and (hetero) normative vs. everything else under the sun. The legacy of the ballroom scene has been, until the last decade or so, completely encapsulated by Livingston’s indie doc, where lingo and references have been so copiously repeated (a la “Ru Paul’s Drag Race”) it’s easy to lose track of their origins, while a throwback homage such as “Pose” devolved across three seasons into spurious soap opera.

To acknowledge the formidable, everlasting impact of Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary Paris is Burning, itself a successor to the recently restored 1968 doc The Queen, part of the conversation must include acknowledgement of appropriation. The privilege of the cultural gatekeeper, as in who gets to convey what stories, etc., has defined our understanding of others through cinematic representation. Obviously, this includes our established, well-hewn conditioning of whiteness and (hetero) normative vs. everything else under the sun. The legacy of the ballroom scene has been, until the last decade or so, completely encapsulated by Livingston’s indie doc, where lingo and references have been so copiously repeated (a la “Ru Paul’s Drag Race”) it’s easy to lose track of their origins, while a throwback homage such as “Pose” devolved across three seasons into spurious soap opera.

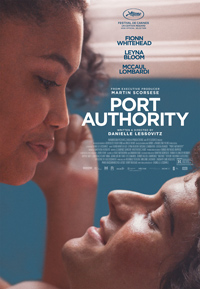

Enter Danielle Lessovitz’s debut Port Authority, a starry-eyed contemporary romance which forces the white heteropatriarchy to catch up with its black and queer trans characters rather than the other way around. It’s a shaggy haired indie romance which captures a certain time and place, and although anachronistic in some regard, attempts a difficult cross-pollination of cultures which, even if not successful, is touching and hopeful.

Twenty-year-old Paul (Fionn Whitehead) arrives in New York’s port authority bus terminal expecting to meet his older half-sister Sara (Louisa Krause), but she’s nowhere to be found and cannot be reached by phone. He spies a group of young people voguing and catches the eye of the beautiful Wye (Leyna Bloom). Falling asleep on a bus and assaulted, Paul is rescued by Lee (McCaul Lombardi), who lives in a homeless shelter he controls access to. It seems Lee works for a landlord who expects him, along with groups of young men he selects at the shelter, to evict various denizens behind on rent or landlord fees. When Paul spies one of Wye’s friends living in the shelter, he follows him one night to a ballroom. Conversation is sparked, but Paul doesn’t recognize Wye is trans while he lies about his living situation. As their romance blossoms, reality sets in, and slowly Paul begins to see what friends and family really look like.

Strangely, Port Authority goes overboard on the homophobia and veritably sidesteps the reality of transphobia altogether, with Lombardi’s Lee and his goons going out of their way at every conceivable moment to bully and ostracize. While Lessovitz does establish a vibrant binary world of ‘chosen’ families, including the benevolence afforded by the ballroom scene and dysfunctional toxic masculinity of Lee as a slumlord protégé, one wonders how the complexities might have been more formidably teased. As it stands, these two familial units take on a pseudo-Shakespearean audacity, albeit fated for a ridiculous and contrived showdown primed from the moment both groups are presented beneath the dark shadow of landlord fees. But if Paul and Wye are stand-ins for those iconic teen lovers doomed by the same stubbornness prized by the Montagues and Capulets, they generate a likeable chemistry all their own.

Fionn Whitehead, and his eventual ‘white boy realness,’ is scrappy and likeable, and together with Lessovitz does a fine job of conveying his own instability. The character work, if sometimes head on, is underlined by his panic-stricken vibe. As his counterpart is the transfixing Leyna Bloom as Wye McQueen (her chosen name throwing out a constant question of deflection, recalling Bronski Beat’s gay anthem), and while some moments requiring heavy lifting sometimes feel stilted, she commands the screen.

Shot by Jomo Fray (Selah and the Spades, 2019) with a score from Matthew Herbert (a favored collaborator of Sebastian Lelio), Port Authority may be far from perfect, but it’s also a vital portrait of adaptability. Lessovitz presents a dynamic pair of protagonists while conveying the resilience of a community who’s mastered building a world of their own. If ballroom was once a mimicry of cultures which rejected, ignored, or demeaned trans lives, it has pivoted into a portrait of what humanity, fellowship and family are supposed to look like. And Port Authority projects this spirit.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆