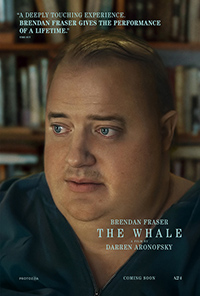

Charlie and the Tragedy Factory: Aronofsky Returns with Potent Chamber-piece on Despair and Redemption

Obesity is far from the only morbid element marinating the bleak apartment of a six-hundred pound Idahoan man in The Whale, Darren Aronofsky’s adaptation of the lauded 2013 play by Samuel D. Hunter. A transformed Brendan Fraser is startling as the central figure, a man desperate to make amends with his estranged daughter during the last week of his life because congestive heart failure is imminent. A penchant for broken families leading themselves to ruin hails back to Aronofsky’s blazing breakthrough Requiem for a Dream (2000), while shades of a troubled father/daughter duo and the (brief) resurrection of Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler (2008) aligns this sordid melodrama within the expected set of exemplary foibles Aronofsky has a knack for.

Obesity is far from the only morbid element marinating the bleak apartment of a six-hundred pound Idahoan man in The Whale, Darren Aronofsky’s adaptation of the lauded 2013 play by Samuel D. Hunter. A transformed Brendan Fraser is startling as the central figure, a man desperate to make amends with his estranged daughter during the last week of his life because congestive heart failure is imminent. A penchant for broken families leading themselves to ruin hails back to Aronofsky’s blazing breakthrough Requiem for a Dream (2000), while shades of a troubled father/daughter duo and the (brief) resurrection of Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler (2008) aligns this sordid melodrama within the expected set of exemplary foibles Aronofsky has a knack for.

In keeping with the play’s single set location in a cramped apartment (which isn’t even fully explored due to the near immobility of the main character), Aronofsky has a difficult time divorcing the film from the aesthetics of the stage, while Hunter’s adaptation of his own prose should have utilized a different approach as regards several key motifs (beyond the utilization of sequences involving online college courses). However, the powerful impact of several performances, most notably Fraser’s, are gripping enough to override the material’s inherent theatricality.

Charlie (Fraser) is a morbidly obese gay man who lives all alone in an apartment while teaching online writing courses at a university, though he never allows himself to be on camera. He’s cared for by Liz (Hong Chau), a no-nonsense nurse who pops in daily to care for him and bring him food, despite how these actions enable him. She’s the only person who cares for Charlie, who was her dead brother Alan’s boyfriend. Together, they stand in defiance of a local church group/cult called New Life, whose guilt mongering played a major part in Alan’s suicide, and the resulting reason for Charlie letting himself go. However, Charlie’s health is quickly deteriorating, as Liz confirms a blood pressure reading of 238/134. But he refuses to go to the hospital. As providence would have it, he’s suddenly visited by Thomas (Ty Simpkins), a missionary for New Life, hellbent on saving one soul from damnation for entirely selfish reasons. And, almost simultaneously, Charlie’s estranged seventeen-year-old daughter Ellie (Sadie Sink), suddenly shows up at his doorstep after a nine-year absence, even though they live in the same town. Ellie is angry, vengeful, and wayward, stemming from her father leaving both her and her mother Mary (Samantha Morton) for Alan all those years ago. It just so happens, Ellie’s welfare is the only thing that’s kept Charlie going as he’s slowly destroyed himself—she just doesn’t know it yet. He interprets her sudden appearance as his final opportunity to do the right thing and make sure she’s okay.

It’s unfortunate some of Hunter’s more explicit subtexts from the play couldn’t have been better absorbed into the visual fabric, particularly the overused reference to Melville’s Moby Dick and a crucial essay bookending the film. Both Melville and Walt Whitman, two of the most iconic gay writers in the literary canon, provide the combative backbone for the religious cult which has swallowed several lives in the narrative, both on and off screen. They’re some brilliantly collected allusions and references, but there are some distracting missteps in how they’re overbaked into the dialogue. Ellie’s rage against the world due to her father’s abandonment, (with Charlie meant to be, from her perspective, like Ahab’s obsessive, life-consuming target), and her eighth grade essay where Melville’s novel reminded her of her own life, is the epiphany she’s pushed towards for Charlie to receive his redemption through forgiveness. Unthinkingly, he wounded his daughter irreparably in pursuit of his own brief happiness. It’s a layered tragedy of how hurt people hurt people, and every once in a while really nails the heartache of self-inflicted damage in response to a reality we cannot change.

Small, often imperceptible kindnesses glancing across the screen are veritable life rafts in this sea of cruelty and cynicism (enhanced exponentially by Aronfsky’s setting of the 2016 US presidential election cycle). Charlie is introduced initially as a disembodied voice in the center square of an online writing course, the visual metaphor for what his life’s been reduced to since the suicide of his younger partner – a void. Last chances and lost souls converge in the final week of Charlie’s life, the evident timeline as the days of the week slip away (why do these deadlines of doom always kick off at the beginning of the week?), and Hunter’s subtexts allow for some powerful interactions regarding the hostile terrain of religion regarding homosexuality. Faith and food become the twin pillars of overzealous agents of ruin, suggesting how both might be considered necessary for physical and spiritual (for those so inclined) sustenance, but can be the tools we use to ruin ourselves. But really, The Whale is about crimes of the heart, with Charlie desperately paying penance for the abandonment of his daughter, a girl burgeoning into a cold, bitter, and cruel young woman.

Fraser is certainly a showstopper here, and his level of emotional prowess of the kind but broken Charlie is so exceptional it often forgives a stagey theatricality Aronofsky can’t quite avoid. But there’s a forced quality to the characterization and thematic use of Ty Simpkins’ Thomas, and the level of dimensionality required for this facet of the narrative to work is rushed over, partly due to the frenetic handling of Sadie Sink’s Ellie, a teen defined almost solely through harshness so over the top it sometimes cracks into camp.

There’s meant to be a maudlin sense of black comedy generated by the heartbreak of Ellie, whose abandonment has sent her on an increasingly volatile trajectory, enhanced by the understandable but equally selfish thought processes of her mother, who refers to her as evil—and some of Ellie’s actions and behaviors are indeed troubling, but more along the lines of a wounded, abused animal than sociopathic. The brief introduction of Samantha Morton’s Mary, whose own personal poison is booze, blasts open another door of jarring disconsolation, but it’s an effective, powerful scene which allows for one of the few authentically emotional revelations of the material. Rivaling Fraser is an equally adept Hong Chau as Liz, a less sensational but doggedly empathetic persona irrevocably tied to Charlie due to her brother’s tragic demise.

Rob Simonsen’s score weaves itself into elements of the sublime in the film’s final cathartic crescendo, the rain soaked Idaho skies broken up by the sun, with Aronofsky’s regular DP Matthew Libatique going for broke with the only real illumination. Although it’s a sometimes rocky path getting there, the grim eloquence of The Whale evens out all of the competing colors in its messy room, generating the feeling of the oft-mentioned Whitman, “the song of me rising from the bed and meeting the sun.”

Reviewed on September 3rd at the 2022 Venice Film Festival – In Competition. 117 Mins.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆