Grace is Gone: Gout’s Aggressive Debut Charts Patterns of Criminality

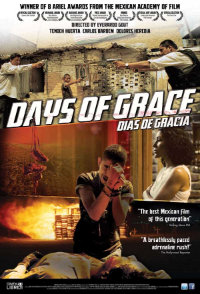

Don’t let the poetic title fool you, as Everardo Gout’s directorial debut Days of Grace does not document an iota of such virtue. As one character points out, “To live in Mexico is to gamble with your life every day.” Belonging to a growing class of Mexican filmmakers determined to recreate the visceral, dangerous realities of everyday existence, Gout’s work is comparable to names like Gerardo Naranjo and Amat Escalante. Drawing upon three thematically related incidents to filter his exploration of violence, Gout chooses a significant waning period, that of the World Cup. The televised event sees crime rates drop by thirty percent as both sides of the law take a break from the usual rampage. While Gout may not reveal anything surprising, his intention to unnerve and agitate is apparent from the first frame, concocting a film that is visually abrasive and headache inducing.

Don’t let the poetic title fool you, as Everardo Gout’s directorial debut Days of Grace does not document an iota of such virtue. As one character points out, “To live in Mexico is to gamble with your life every day.” Belonging to a growing class of Mexican filmmakers determined to recreate the visceral, dangerous realities of everyday existence, Gout’s work is comparable to names like Gerardo Naranjo and Amat Escalante. Drawing upon three thematically related incidents to filter his exploration of violence, Gout chooses a significant waning period, that of the World Cup. The televised event sees crime rates drop by thirty percent as both sides of the law take a break from the usual rampage. While Gout may not reveal anything surprising, his intention to unnerve and agitate is apparent from the first frame, concocting a film that is visually abrasive and headache inducing.

Set during three separate periods, 2002, 2006, and 2010, Gout melds three separate incidents into an evolving revolution of movement. As events unfold, the film is not clearly demarcated or chronological, edited together for a visceral wallop. We start in 2002 as an overly well-intentioned cop, Lupo Esparza (Tenoch Huerta) attempts to teach two young kids a lesson for selling drugs. One of the boys, Doroteo is involved in the latest segment as part of kidnapping gang (Kristyan Ferrer), abducting a man for ransom (Carlos Bardem). Doroteo bonds with the victim inbetween rounds of ruthless torture, while the man’s wife (Dolores Heredeia) is left to scrape up the dough. As we switch back and forth between time frames, we see Lupo become more invested in his heroic intentions, invited by a crooked superior to become involved in taking out a drug ring run by a woman known as the Madrina (a striking Veronica Falcon). When his own family is compromised, Esparza is fooled into thinking the Madrina is responsible, but this turns out to be a ruse involving his own partner as means to usurp her territory.

There’s a queasy pallor to Days of Grace, which seems to ooze with putrid yellows and greens. DoP Luis David Sansans (Escobar: Paradise Lost) frames subjects through prisms and at odd angles, each sequence a sensory overload that feels akin to the perspective of a drunken insect in the room being tossed around. Three separate editors are credited including Almodovar’s regular Jose Salcedo, Jeunet’s regular Herve Schneid, and Gout Valerio Grautoff. The mixture should come as no surprise, since Days of Grace is a feat of spliced footage that’s impressively put together.

Though its whirling cast of characters and effortless maneuvering through three periods often causes purposeful disorientation, Gout’s screenplay (including credited dialogue from David Rustala) is a mixture of the usual roundelay of criminal epithets (the Madrina threatens Esparza with the riff “Hell hath no fury like a criminal scorned”) and a handful of delicious lines like, “When it comes to money, love dies.” As a canvas of violence during what counts as the country’s downtime, Days of Grace effectively accomplishes what it sets out to do, conveying a specific realism, as evidenced by its depiction of a female kingping like Madrina, a character that English speaking directors would have morphed into fantasy, like Oliver Stone’s use of Salma Hayek in Savages (2012).

Premiering as a Midnight Screening at Cannes 2011, it’s interesting to compare the reception and release of Gerardo Naranjo’s Miss Bala, another violent crime film that opened at the same film festival (in Un Certain Regard) and reached international release the same year. In that substantially more violent film, Naranjo tacks a message on his finale concerning the country’s crime rates, yet Gout’s film stands as a more successful testament to the instability of the landscape.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆