Letters to Daddy: Grassadonia & Piazza Continue Their Cosa Nostra Sagas

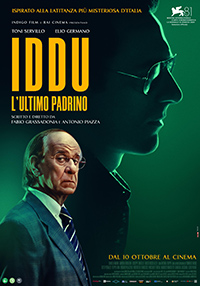

Italian directors Fabio Grassadonia and Antonio Piazza reimagine the circumstances surrounding yet another mafioso tale with their third feature, Sicilian Letters. Freely inspired by events in Sicily from the 2000s, their introductory title cards reveal this tale is one where “reality is a point of departure, not a destination.” The Italian title, Iddu, is the nickname of a straggling mafia boss still being sought by law enforcement who have devised a circuitous plan to draw him out of his hideout. Starring two of Italian cinema’s most notable contemporary actors, Toni Servillo and Elio Germano, it is the directors’ most mainstream offering to date. Light attempts at satirical relief through its social commentary, their latest is more of a cop drama than a gangster flick, but the mixture of corresponding perspectives doesn’t really build to the kind of climax which would seem to justify its elaborate attempts to convince otherwise.

Italian directors Fabio Grassadonia and Antonio Piazza reimagine the circumstances surrounding yet another mafioso tale with their third feature, Sicilian Letters. Freely inspired by events in Sicily from the 2000s, their introductory title cards reveal this tale is one where “reality is a point of departure, not a destination.” The Italian title, Iddu, is the nickname of a straggling mafia boss still being sought by law enforcement who have devised a circuitous plan to draw him out of his hideout. Starring two of Italian cinema’s most notable contemporary actors, Toni Servillo and Elio Germano, it is the directors’ most mainstream offering to date. Light attempts at satirical relief through its social commentary, their latest is more of a cop drama than a gangster flick, but the mixture of corresponding perspectives doesn’t really build to the kind of climax which would seem to justify its elaborate attempts to convince otherwise.

Palumbo Catello (Servillo), aka the ‘Headmaster,’ has just been released from prison only to find life back home has drastically changed. His wife and daughter have been forced to move to a smaller apartment, and, worse, his daughter has married and is pregnant by the doltish janitor (Giuseppe Tantillo) of the school he used to be head of. A career politician, who also used to serve as mayor, Catello has deep rooted ties to Sicily’s underbelly, and is tapped by the Italian intelligence service for a covert operation. Catello is the godfather of Matteo Messina Denaro (Germano), whose father Gaetano has just died, making him the last mob boss standing. Only Matteo has been in hiding for years. Catello, who has been left in crippling debt after his prison sentence, gets the officials to cease plans to demolish his last asset, a partially built hotel on Denaro’s territory. He agrees to serve as go-between if he can utilize this as a way to receive Denaro’s approval and assistance with overcoming the current Mayor’s obstacles which have stymied completion of the project. Approved to write Matteo a pizzini (a coded note or letter), which is currently the only way to communicate with him, the plan seems to be going smoothly until Matteo’s estranged, unrecognized child becomes part of the equation.

What’s most surprising about Sicilian Letters is it’s various attempts at blatant crowd pleasing, and plays more like a B movie than their previous efforts, such as 2013’s Salvo and 2017’s Sicilian Ghost Story, both films mining the violent, devastating effects of organized crime on both innocent bystanders and active participants. But those previous films were long gestating narratives bolstered by arthouse approaches. Sicilian Letters starts out like a crackling comedy as soon as Servillo hits the scene, defecated on by a bird as he leaves prison after serving a six-year prison sentence (though he maintains his innocence, of course).

Elio Germano’s Matteo, introduced via a childhood flashback as the youngest son of the ruthless Gaetano who displays a penchant for bloodletting, provides more of the sinister element, but both men are engaged with parallel experiences involving a female cohort. An ancient, priceless artifact known as “Pupu” was passed down amongst their family for generations (not unlike the racket explored in Alice Rohrwacher’s La Chimera, 2023). Pupu has since been seized by officials and is now on display in a museum. Matteo is given refuge by a woman (Barbora Bobulova) who’s indebted to Matteo for murdering the man who killed her husband. An unforeseen situation with a neighbor next door allows them to bond when they burn the inconsiderate fool’s amateur vineyard to the ground. A majority of the focus ends up in the lap of Servillo and the honest cop who’s trying to do the right thing, Inspector Rita Mancuso (Daniela Marra). Her boss, played by Fausto Russo Alesi, has no interest in ever capturing Matteo since he’s also in the Denaro family pocket, meaning this covert operation will only really harm Catello.

Quite predictably, contentious relations between fathers and sons are both the dramatic catalyst and the eventual undoing of Catello and Mancuso’s plan to work this tenuous situation from their own angle. From the film’s opening shot, which is revealed to be reflected light from a goat’s eyeball, starts a series of visual motifs involving warped reflections. Everyone is corrupt, and if they aren’t, they’re easily corruptible. Easily the best moments of the film are shared by Servillo and the fraught relationship with his cynical wife, played by a withering Betty Pedrazzi. “Intelligence is an overrated gift,” she sniffs at her hustling husband.

While Bobulova is a rather tight-lipped characterization, other supporting women are caricatured cliches, such as a fun but ultimately silly Antonia Truppo as Matteo’s power hungry harridan of a sister, and the self-righteous inspector played by Marra. Considering reality was the departure point, the filmmakers somehow fall short with their possibilities, choosing a perplexing, rather underwhelming destination, which crash-lands into a finale. A closing moment focuses on a missing puzzle piece, but then, nothing was really ever puzzling.

Reviewed on September 5th at the 2024 Venice Film Festival (81st edition) – In Competition section. 122 Minutes.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆