The Interest of Distance: Yeo Discovers the Masochistic Pleasures of a Surveillance State

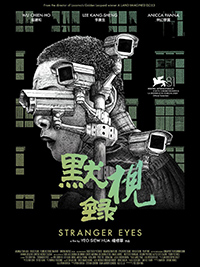

“Strange feeling that someone is looking at me. I am clear, then dim, then gone, then dim again, then clear again, and so on, back and forth, in and out of someone’s eye.” Samuel Beckett’s passage from Happy Days crystallizes the convoluted intrigue behind Singaporean director Yeo Siew Hua’s sophomore feature Stranger Eyes. Following his 2018 Golden Leopard winning debut A Land Imagined, Yeo once again explores similar themes on the overwhelming presence of absence, and again, a complex investigation of something labyrinthine ensues. A missing child is the jumping off point for the exploration of our innate responses to being observed, or, rather, feeling seen while under a state of constant surveillance, both by our loved ones and those behind eyes in the sky we will never see. A chance circumstance allows for a collision of sorts. But what feels initially a sinister lens to explore meaningful behavioral truths gets a few too many turns of the screw with a third act dollop of melodrama.

“Strange feeling that someone is looking at me. I am clear, then dim, then gone, then dim again, then clear again, and so on, back and forth, in and out of someone’s eye.” Samuel Beckett’s passage from Happy Days crystallizes the convoluted intrigue behind Singaporean director Yeo Siew Hua’s sophomore feature Stranger Eyes. Following his 2018 Golden Leopard winning debut A Land Imagined, Yeo once again explores similar themes on the overwhelming presence of absence, and again, a complex investigation of something labyrinthine ensues. A missing child is the jumping off point for the exploration of our innate responses to being observed, or, rather, feeling seen while under a state of constant surveillance, both by our loved ones and those behind eyes in the sky we will never see. A chance circumstance allows for a collision of sorts. But what feels initially a sinister lens to explore meaningful behavioral truths gets a few too many turns of the screw with a third act dollop of melodrama.

A child named Little Bo gets nabbed from her father Junyang (Wu Chien-Ho) one day at the park. Three months have passed since her disappearance, leaving him and his wife Peiying (Anicca Panna) to pore over old family footage looking for potential clues. One day, they begin receiving unmarked DVDs slipped under the door, which shows someone has been observing them far afar for quite some time, filming some of their most private moments. The footage is handed over to the police, who advise the couple to sit tight. It just so happens, Peiying also has had a secret admirer, attention she has used to fill a void between the couple that’s been growing for some time. Without any further information from the police, they decide to turn the tables on this ‘stalker,’ who they believe is responsible for taking their child.

It’s impossible not to think of Michael Haneke’s masterpiece Cache (2005) in the early set-up of Stranger Eyes. Likewise, the obsessive deciphering of clues on a case seemingly gone cold, such as Shohei Imamura’s 1967 A Man Vanishes. Once Lee Kang-sheng (notable for his collaborations with Tsai Ming-Liang) shows up as a lonely grocery store manager and is revealed to be responsible for stalking the couple, the tension abates considerably. Instead, it becomes an exercise in voyeriusm, but not in a way suggesting the genre trappings Rear Window (1954) or Peeping Tom (1960). It’s clear he cannot possibly be the culprit who kidnapped Little Bo (a name which begs one to add ‘peep’ to it), even though the strained couple can think of no better avenue to pursue. The missing child is really the red herring masking the coincidental focus, a theme asserting there’s a potential perverse thrill in being looked at, just as much there is for those who take pains to elude being observed.

As it happens, Peiying has enjoyed the attention of the stalker, which also says a lot about the joy she derives from her hobby, putting on live shows as a DJ on YouTube. She’s felt invisible to her husband, the inevitable consequence of proximity or prolonged looking—we become desensitized when we stare too long. Or, when objects have the agency to look back. The titillation is the power imbalance, and there is certainly a S&M type dynamic between the observer and the observed. But, just as there might be a certain thrill in being watched, when we forget ourselves and let our guards down, with great dismay it becomes apparent we also cannot escape it.

Belgian composer Thomas Foguenne heightens the sense of intrigue during the film’s unpredictable midsection, particularly as we get to experience Junyang’s more aggressive ways of seeking the physical pleasure he cannot procure at home (which includes a threesome in the locker room with a couple he works with). Another lop siding obstruction is how Wu Chien-Ho and Lee Kang-sheng tend to feel like more well rounded characters than their female counterparts. We never quite get a sense of Annica Panna, only that the film tends to position her the same way in which her character feels. And Vera Chen as the live-in mother of Junyang is on hand to be a beautiful but nagging referee.

The multi-hyphenate Pete Tao seems to pop up in the nick of time as the aloof but lightly amused Officer Zheng, finding Little Bo in the way we should have predicted—by poring over CCTV footage. If only the worried couple had taken a moment to realize the police would have also compared alternate sources of time stamped footage corresponding with the filmed segments their stalker was sending them. But when the kidnapping bubble bursts, Yeo Siew Hua gives us another unnecessary twist with an extra half hour of narrative which feels completely erroneous, as Junyang begins to stalk Lao Wu based on a hidden baggage of DVDs containing footage of another young woman being stalked. It’s too bad Stranger Eyes didn’t quit while it was ahead, when the focus was a solid exercise about how the closer we get to things the less we might see. Or how the longer we look at images, the more we might erroneously fill in the blanks with our own projections.

Reviewed on September 5th at the 2024 Venice Film Festival (81st edition) – In Competition section. 125 Minutes.

★★/☆☆☆☆☆