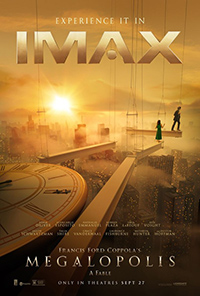

Atlas Farted: Coppola’s Labor of Love a Lackluster Saga

While he’s one of the greatest film directors of all time, mostly thanks to a handful of films he delivered during the 1970s New American Cinema movement, Francis Ford Coppola’s long-gestating, wholly self-financed Megalopolis is an unfortunate dud rife with archaic tendencies and stillborn ideas. Out of touch in almost every conceivable way, it’s the riskiest endeavor of his career, which is saying something considering the innovative risks taken with some of his greatest achievements (Apocalypse Now, 1979) and formidable financial misfires (One From the Heart, 1981). His latest (and likely last) feature exemplifies all the follies of auteurs who have gone to seed, and is a prime example of why it’s necessary for all creatives to sometimes kill their darlings.

While he’s one of the greatest film directors of all time, mostly thanks to a handful of films he delivered during the 1970s New American Cinema movement, Francis Ford Coppola’s long-gestating, wholly self-financed Megalopolis is an unfortunate dud rife with archaic tendencies and stillborn ideas. Out of touch in almost every conceivable way, it’s the riskiest endeavor of his career, which is saying something considering the innovative risks taken with some of his greatest achievements (Apocalypse Now, 1979) and formidable financial misfires (One From the Heart, 1981). His latest (and likely last) feature exemplifies all the follies of auteurs who have gone to seed, and is a prime example of why it’s necessary for all creatives to sometimes kill their darlings.

In the waning days of a decadent metropolis called New Rome, the newly anointed Mayor Cicero (Giancarlo Esposito) has inherited a city in financial turmoil. His rival is an architect, Caesar Catalina (Adam Driver), head of the city’s Design Authority division who has the power to stop time. Catalina has also created a new metal, Megalon, with which he plans to revitalize the city’s infrastructure, against the Mayor’s wishes. Cesar is also having an affair with infamous stunt journalist, Wow Platinum (Aubrey Plaza), whose hunger for power leads her to marry the city’s most financially powerful man, Hamilton Crassus III (Jon Voight), her lover’s uncle. Hamilton’s grandson Clodio (Shia LaBeouf) desires to inherit this empire, no matter the cost, which means destroying his cousin Caesar in some way.

As we move through the insidious upper echelons of New Rome, none of whom are likable or necessarily interesting, a semi-coherent plot seems to slip into a realm of spackled nonsense. Considering the much publicized budget footed by Coppola himself, it’s almost shocking how cheap everything still feels, a hazy green screen only furthering comparisons to some over-budgeted 1990s turkey trying to be futuristic. While the narrative is clearly about the end of an empire, hastened by the continual struggle for power between three elitist factions who vie for the uppermost hand, it’s also ironically about humankind’s hubris. Much like the elitists hungry for control in New Rome, Coppola himself seems to have flown too close to cinema’s sun.

The narrative’s hero is, more or less, Adam Driver’s Caesar Catalina, inventor of a new element called Megalon, an indestructible building block with which, as the head of the Designing Authority agency, he will use to rebuild the city, Megalopolis. Of course, he must contend with Esposito’s Mayor, whose plans for the same space are a ‘fun’ casino called City Fair. Either way, those who had been living in the area have had their houses razed, so no one seems entirely happy with either of them. The set-up feels about as deliriously out of touch as Ayn Rand thinking she could modernize Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar and brazenly announce it as the most brilliant piece of literature ever written.

Driver and Esposito each navigate their roles easily enough, and the dulcet tones of Laurence Fishburne, playing Caesar’s right hand man, aids in providing a semblance of structure. But Coppola once again confirms he can’t quite write roles for young women, nor seem to be able to rightly direct the beautiful ladies playing them. Like a curse overshadowing a garbage dump, a doe-eyed Nathalie Emmanuel wanders around like the prototype for an ingenue robot, supposedly attracted to Caesar while she mechanically delivers Coppola’s insanely pretentious dialogue.

While she fares a bit better, Aubrey Plaza is high camp as a gold digging news anchor utilizing Wow Platinum as a nom de plume we’re supposed to take seriously. Plaza exudes the same kind of self awareness Gina Gershon delivered in Showgirls (1995), and, at the very least, seems to be enjoying herself. On the plus side, Megalopolis gives us an unforgettable moment where Jon Voight denounces her as a ‘Wall Street slut” before shooting an error at her heart while she’s wearing a Cleopatra inspired outfit usually donned by those about to perform a naughty pole dance.

Of course, there’s more insanity going on with Shia LaBeouf’s Clodio Pulcher, Caesar’s cousin who has designs on taking over his grandfather’s banking empire. In the film’s most extravagantly Babylonic moment, the wedding of Wow and Crassus turns into a fundraising drive for the city while a virginal Taylor Swift-ish popstar named Vesta Sweetwater (Grace VanderWaal), who performs a song about her pledge to remain unsexed until marriage while the wealthy attendees are asked to donate oodles of money to assist in her vow. Clodio has doctored footage of Vesta in the arms of Caesar, shown after her performance ends, causing pandaemonium.

All of these competing characters eventually make Megalopolis feel overstuffed with ideas never fully realized (there’s also a Soviet satellite set to crash into the atmosphere). Not to mention a coterie of folks on the sideline, including a wealthy ‘fixer’ played by an underutilized Dustin Hoffman, D.B. Sweeney as a haggard Commissioner, Chloe Fineman as a coked-out socialite, Talia Shire as Caesar’s mentally ill mother, Jason Schwartman as the Mayor’s helpmate, and Kathryn Hunter as the Mayor’s current wife, who gets to say lofty things like “Only those in a nightmare are capable of praising the moonlight.”

The score from Osvaldo Golijov (who worked with Coppola on Youth Without Youth and Tetro) sometimes recalls Terence Blanchard, but more often sounds like generically light filler edited into a cheapie indie flick. Strangely, a novel attempt at breaking the fourth wall by trotting out an ‘actor’ on stage to play a journalist questioning Cesar onscreen also adds to the unnecessary excessiveness of it all, ultimately giving us lots of nothing when it’s not parroting ideas already explored elsewhere to greater effect. At worst, Megalopolis feels somewhat agonizing to sit through. At its best, it’s quite boring.

Reviewed on May 16th at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival – Competition. 138 Mins

★/☆☆☆☆☆