Thief of Hearts: Lellouche’s Sprawling Romance Has Arrhythmia

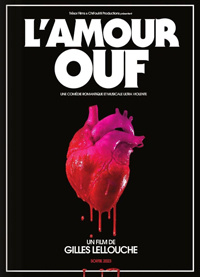

A common occurrence for actors moonlighting as directors is not knowing how to hone a focus, crafting a narrative around the performers, often to the detriment of the film itself. Such is the case with Beating Hearts (L’amour Ouf), the third film directed by Gilles Lellouche, an actor who often oscillates between comedy and drama, and has thus far focused on lighter, frivolous fare as a director. The French language title of his latest roughly translates to Phew, Love, which gives a better indication of the irreverent tone aimed for in this violently stylized romantic melodrama, clocking in at nearly three hours, the justification of which never arrives. Lellouche, adapting from the novel written by Neville Thompson with the assistance of scribes Audrey Diwan (!), Julien Lambroschini, and Ahmed Hamidi, seems to be going for broke but ends up going absolutely nowhere with this rambling heap of empty-headed nonsense which seems to actively avoid following its own instincts.

A common occurrence for actors moonlighting as directors is not knowing how to hone a focus, crafting a narrative around the performers, often to the detriment of the film itself. Such is the case with Beating Hearts (L’amour Ouf), the third film directed by Gilles Lellouche, an actor who often oscillates between comedy and drama, and has thus far focused on lighter, frivolous fare as a director. The French language title of his latest roughly translates to Phew, Love, which gives a better indication of the irreverent tone aimed for in this violently stylized romantic melodrama, clocking in at nearly three hours, the justification of which never arrives. Lellouche, adapting from the novel written by Neville Thompson with the assistance of scribes Audrey Diwan (!), Julien Lambroschini, and Ahmed Hamidi, seems to be going for broke but ends up going absolutely nowhere with this rambling heap of empty-headed nonsense which seems to actively avoid following its own instincts.

Sometime in the 1980s in North East France, Clotaire (Malik Frikah) is a rebellious teenager who seems determined to drop out of school to live in the moment. A hellion towards his fellow classmates, save a select handful of minions, including his foster brother Kiki, his behavior is somewhat tamed by the arrival of Jackie (Mallory Wanecque), a headstrong, ambitious girl recently expelled from Catholic school for insolence, and now enrolled in the public system. She challenges Clotaire’s behavior and before they know it, are both head over heels in love. But after stealing a stash of hash from local kingpin La Brosse (Benoit Poelvoorde), Clotaire becomes the affable gangster’s protege. When an armored truck robbery goes haywire, Clotaire gets left behind, taking the rap and is sentenced to twelve years in prison due to the murder of an armored car driver. A decade later, Clotaire (Francios Civil) is released, immediately trying to track down Jackie (Adele Exarchopoulos), devastated to learn she’s married to Jeffrey (Vincent Lacoste), a middle manager at a car rental company. Suddenly, Clotaire has nothing to live for yet again, and when his old boss refuses to pay him his share, plus interest, from the robbery, all hell breaks loose.

What’s ultimately wrong with Beating Hearts is it wants to evoke too many kinds of elements as a main focus, and appears to have been adapted without properly condensing its pulpy themes. Initially, it would seem Lellouche wants to recreate the Cinema Du Look movement while also fashioning a Scorsese style gangland opus, elements which actively work against one another to the point of eroding it all to generic tendencies. The ‘mad love’ wrong-side-of-the tracks style attraction between Jackie and Clotaire never feels believable, and we spend half of the film’s running time watching their love supposedly blossom as teenagers. Absolutely none of these moments create a rational portrait of such an enduring, formative connection, especially as Clotaire descends into a criminal netherworld run by Benoit Poelvoorde (giving Robert Englund energy) who loves to sing karaoke.

Casting is also a major hurdle Beating Hearts never overcomes. Karim Leklou and Elodie Bouchez (who is shamefully underutilized) rear a gaggle of foster kids, where it seems light verbal abuse and working class apathy led to Clotaire’s cemented status as an obnoxious, hyper violent miscreant. Alain Chabat fares a bit better (though the de-aged sequences when Jackie is young should have landed on the editing room floor) as Jackie’s papa, but again, Lellouche can’t rightly characterize any of them, tossing superficial details ultimately sterile or downright meaningless. As the adult versions of these star-crossed lovers, Adele Exarchopoulos gives an emotionally appropriate performance, but seems uncomfortably detached from both Francois Civil and Vincent Lacoste (the latter revealed to be an abusive control freak, but despite finding time to pad out everything else, the script resists mentioning this marriage to a wealthy-ish man was simply a convenience for a depressed woman to live comfortably). The film also strangely presents a woman who more closely resembles Wanecque as the young Jackie, whom Clotaire picks up at the club. Strangely, the script enhances an Emperor’s New Clothes move by having characters tell Exarchopolous she looks exactly the same as she did a decade prior. It’s on par with a similar ridiculous romance she was part of in Michael R. Roskam’s Racer and the Jailbird (2017).

Jean-Pascal Zadi provides ruinous attempts at comic relief as Lionel, the adult version of Clotaire’s bestie, another version of the goofball he’s apparently going to be typecast as for a while (utilizing the same shtick in Laetitia Dosch’s corny Dog on Trial, 2024, the only difference being his Fresh Prince of Bel-Air fade here). Raphael Quenard and Anthony Bajon are also on hand, though merely pawns for the destructive urges in Clotaire’s i’ll-fashioned thirst for revenge, the ultimate goals of which remain unclear (not to mention the gang of henchmen he assembles about as easily as saying abracadabra). Through a series of choreographed dance sequences, fistfights, gun violence, and pulsating club scenes, Lellouche doesn’t seem to know how to end this effectively other than pepper spraying the final ten minutes with a cascade of sentimentality. L’amour ouf finally becomes Ouf, C’est Fini.

Reviewed on May 23rd at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival – Competition. 166 Mins.

★½/☆☆☆☆☆