New Year’s Evil: Wheatley Finds Humanity Amid Caustic Bickering

Shapeshifting his way along a varied filmography, Ben Wheatley is back after the tongue-in-cheek gunplay bonanza of Free Fire (review) with a more straightforward, smaller-scale family drama centered around a New Year’s Eve ill-fated party. Words do hit like cannons, however, in Happy New Year, Colin Burstead – a dark and almost nihilistic (though not deprived of Wheatley’s customary twisted humor) catalog of the worst fears people may have when they go back to visit their relatives for the holidays. Quickly shot on single location, and brought to life collectively and collaboratively by an ensemble cast, Wheatley’s latest could have been a minor curiosity to keep the creative juices flowing in-between bigger projects, but there’s definitely more under the surface of this relentless barrage of recriminations and reckonings.

Shapeshifting his way along a varied filmography, Ben Wheatley is back after the tongue-in-cheek gunplay bonanza of Free Fire (review) with a more straightforward, smaller-scale family drama centered around a New Year’s Eve ill-fated party. Words do hit like cannons, however, in Happy New Year, Colin Burstead – a dark and almost nihilistic (though not deprived of Wheatley’s customary twisted humor) catalog of the worst fears people may have when they go back to visit their relatives for the holidays. Quickly shot on single location, and brought to life collectively and collaboratively by an ensemble cast, Wheatley’s latest could have been a minor curiosity to keep the creative juices flowing in-between bigger projects, but there’s definitely more under the surface of this relentless barrage of recriminations and reckonings.

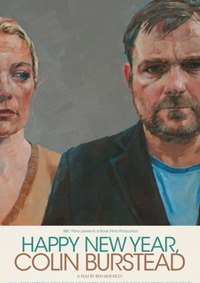

Wheatley’s oldest and truest avatar Neil Maskell stars as Colin, a tightly-wound and contradictory man who comes up with the idea of a party in a Dorset mansion for the entire extended family while at the same time barely concealing his contempt for many of its members. The opening scene already finds him faking reception issues to get out of a call with his sister Gini (Hayley Squires in a performance of raw, grounded humanity similar to her effective turn in Peter Strickland’s In Fabric) who’s throwing a wrench in Colin’s plan by inviting Sam Riley’s estranged third brother David to the celebrations. In a sprawling script that can barely service all of its players and often has to reduce them to single-trait characters, Maskell is the standout: bursting at the seams, at once instigator and victim of the group’s conflicts, he’s genuinely trying to help but blindly lighting fires in each room he steps into.

Threads are left loose and conversations abandoned just like they would in real life; Wheatley leaves you wanting more, for instance with Charles Dance’s terminally-ill Uncle Bertie, though the sense the night could have gone in many different directions adds to the fleeting roughness of the experience, and helps to avoid the biggest pitfall of the genre – the temptation of packaging the chaos too neatly. That has never been a danger for Wheatley, at least in his early filmography, and not coincidentally he seems to tap into the same spiky atmosphere of titles like Kill List and Sightseers.

It’s only when the dust has settled that you realize all the ways in which this feels different than a traditional movie family. It’s the costumes, so comically and uniformly mournful in their dark shades that you’d be forgiven for mistaking the film for an elaborate afterlife allegory; it’s the casual but traversal examination of contemporary Great Britain, which feels organically political in its updating of Mike Leigh-esque conventions; and it’s the unusual generational tilt that does away with influential parents to thrust their (not entirely ready) children into the spotlight, subverting the more deeply ingrained tropes about household power dynamics while keeping a distinct patriarchal spin in play.

In a sub-genre that is largely defined by the specificity of its set-up (anything from Festen to Desplechin’s A Christmas Tale), Happy New Year, Colin Burstead leaves the deepest of marks with its resolutions – the way things deflate, implode and are cruelly reabsorbed into the incoming new year. Its characters are obsessed with doing something even when they’re not sure it’s the right thing, and Wheatley makes this invisible pressure an almost perceptible feature of his every shot. When faced with the inefficiency of their methods, they expel themselves from the collective, taking a brief respite into the night. Are they saving or sacrificing themselves? What is clear is that it’s the quietest and most surgical act of violence this director has ever depicted.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆