Don’t Let’s Ask For the Moon: Nolan’s Space Opera for the Ages

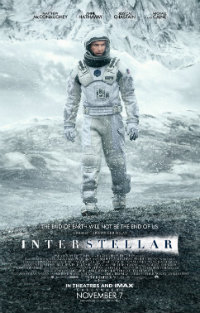

At last divorcing himself from the omnipotent shadows of Batman, director Christopher Nolan’s latest, Interstellar, returns to the heady, theoretical sci-fi that graced his equally ambitious 2010 title Inception, wherein Avant Garde concept courted mainstream appeal. Already the source of wildly enthusiastic praise and acclaim, with filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino announcing the film to be equal to the philosophical sci-fi of Tarkovsky and the meditative cinematic poetry of Malick, Nolan has indeed crafted an object of great beauty worthy of such egregious admiration. As far as a masterful visualization of space and an exploration of profound theory, it belongs on a shortlist of must see films which it’s comparably akin to, from Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey to Cuaron’s Gravity. But Nolan’s film falls short in other realms, namely the human component, including a scattering of familial issues goading the film’s dramatic thrust. Not only swallowed by the visual spectacle of Nolan’s achievement, some of them are also clumsily administered as the narrative blearily thrusts them into relativity’s cruel masquerade.

At last divorcing himself from the omnipotent shadows of Batman, director Christopher Nolan’s latest, Interstellar, returns to the heady, theoretical sci-fi that graced his equally ambitious 2010 title Inception, wherein Avant Garde concept courted mainstream appeal. Already the source of wildly enthusiastic praise and acclaim, with filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino announcing the film to be equal to the philosophical sci-fi of Tarkovsky and the meditative cinematic poetry of Malick, Nolan has indeed crafted an object of great beauty worthy of such egregious admiration. As far as a masterful visualization of space and an exploration of profound theory, it belongs on a shortlist of must see films which it’s comparably akin to, from Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey to Cuaron’s Gravity. But Nolan’s film falls short in other realms, namely the human component, including a scattering of familial issues goading the film’s dramatic thrust. Not only swallowed by the visual spectacle of Nolan’s achievement, some of them are also clumsily administered as the narrative blearily thrusts them into relativity’s cruel masquerade.

Mankind’s ability to sustain life on Earth has been dwindling for some time. As food shortages have effected populations globally, militaries have been disbanded, and professionals have been forced to turn to agriculture to squeeze whatever crops they can out of Earth’s deadening soil, which is drying up and virtually blowing all over. Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) is an engineer and a pilot forced into farming corn and raising his two children with the help of his father (John Lithgow). His bright younger child, Murph (Mackenzie Foy) thinks that something perhaps supernatural has been contacting her via Morse code with the bookshelf in her room, and she deciphers coordinates. Curious, Cooper visits these coordinates with his daughter and discovers that NASA, with the help of Professor Brand (Michael Caine) and his daughter Amelia (Anne Hathaway) have discovered a wormhole by Saturn that leads to a galaxy that may possibly be viable for human existence. A crew needs to examine the three planets that a first wave of lone scientists were sent to scope out ten years prior. Though they aren’t quite sure how Cooper stumbled onto their compound, Brand requests his assistance in the mission, which means leaving behind his children as they grow, not knowing if or when he would be able to return.

McConaughey cuts a striking swath through all of the other characters in Interstellar, which reaches its emotional potential early on in its depiction of a father leaving behind his children in order to secure their future. But this is stunted considerably once these children become adults and turn into Casey Affleck and Jessica Chastain, the former whose blue collar farming destiny is depicted as denying him logic or empathy as concerns saving his family while the brokenhearted woman Chastain portrays is gracelessly forced to contend with the film’s ghostly supernatural element which is all too neatly administered—it’s high minded hypothesis is hardly a surprise during the third act reveal, though its logistics will doubtlessly inspire many post-screening discussions.

In particular, Hathaway is something of a glaring weak point in the film’s bid for a certain semblance of cohesion and logic. Spiraling towards their destined wormhole just outside of Saturn and amidst several discussions concerning relativity and time passing by quickly on the world they left behind, her ultra-chic hairdo remains distractingly intact while her icy demeanor melts away a bit too neatly. A cavalcade of familiar faces are showered throughout the rest of the film, many granted only one sequence, like William Devane and David Oyelowo, while Ellen Burstyn, John Lithgow, Michael Caine, and Topher Grace are used sparingly.

Matt Damon plays a late addition to the proceedings, demonstrating the film’s insistent refrain that mankind is its own worst enemy, with each individual unable to override their selfish instincts for self-preservation. During an intense spatial showdown, Nolan juxtaposes a more banal incident going on with Chastain’s Murph on Earth. The result in this instance curiously highlights the lack of energy and innovation that’s been set aside for the doomed terrestrial creatures. A period of over two decades have passed, with Cooper leaving just as corn became the last viable crop to feed Earth’s denizens. Yet, most likely due to the more interesting aspects going on in space, not much can be said for the drying out globe below—it just got even dustier.

Many will surely label Interstellar a masterpiece. While it certainly courts that status, especially compared to the output of similar stature in American film, there’s an inescapable aura of hokum that rears its head throughout. All the talk about chosen ones, future human technological advances we can still only fantasize about, the obsession with retaining hope for the future of the human race even after senselessly destroying our own planet, recalls the thinly veiled metaphors of 1950s era sci-fi (a minor character delivers an ‘aw shucks’ line with deadening corniness late in the film, “Well, she is Murph Cooper!”).

Leaving behind Wally Pfister, Nolan employs Swiss DoP Hoyte Van Hoytema, who was responsible for the beautiful visuals of Tomas Alfredson’s last two films as well as Spike Jonze’s Her (2013), and his masterful work on Interstellar recalls the breathtaking spectacle of what cinema used to seem capable of a lot more often. Equally noteworthy is Hans Zimmer’s ambient score, enhancing the tension, emotion and danger forever on the periphery. But perhaps most interestingly of all, Interstellar points to exciting narrative possibilities, leaving us in the hands of a brave new world run by, saved by, manufactured by woman, both on Earth and far away. We don’t get to see what that looks like, but it leaves us with a delicious pair of possibilities as concerns the uncharted ambitions of humankind.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆