Riding in Cars with Directors: Panahi’s Continued Cinema of Resistance

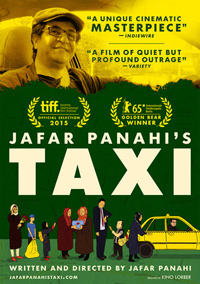

Sanctioned Iranian auteur Jafar Panahi’s Taxi took home the 2015 Berlin Film Festival’s top prize, the Golden Bear, is the third consecutive secret project from the filmmaker, still in the early stages of his twenty year ban from directing. The global cinematic audience has vehemently championed Panahi’s compromised works he’s valiantly managed to assemble and sneak out of the country, beginning with 2010’s angry This is Not a Film and the equally ruminative Closed Curtain in 2013.

Sanctioned Iranian auteur Jafar Panahi’s Taxi took home the 2015 Berlin Film Festival’s top prize, the Golden Bear, is the third consecutive secret project from the filmmaker, still in the early stages of his twenty year ban from directing. The global cinematic audience has vehemently championed Panahi’s compromised works he’s valiantly managed to assemble and sneak out of the country, beginning with 2010’s angry This is Not a Film and the equally ruminative Closed Curtain in 2013.

Surprisingly, his latest projection is quite jovial by comparison, perhaps due to Panahi’s ability to adapt to these filmmaking prohibitions, replacing his standing prison with a mobile one this time around, roving around Iran within the confines and anonymity afforded transportation vehicles. Potentially inspired by fellow Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami, who frequently films sequences in moving vehicles, including the entirety of his 2002 film Ten, it’s perhaps Panahi’s continuous zeal despite insurmountable circumstances which makes his latest so infectious. As with his previous two features, however, there’s the nagging impression of critical overcompensation afforded Panahi’s compromised, constrained cinema of rebellion.

Two passengers argue over arbitrary matters in a taxicab, filmed from a camera attached to the dashboard. As their conversation peters off, we realize it is Jafar Panahi driving the taxi himself, engaging with people we come to recognize as performers in his continued playfulness with form and cinematic artifice. The next passenger is a video store clerk who recognizes Panahi after pointing out the previous inhabitants were quoting directly from Panahi’s 2003 film Crimson Gold.

Panahi’s taxi driver doesn’t recognize the store owner, who relates a complicated memory of certain American titles Panahi would request to rent for his son. It’s explained this type of entertainment is hard to come by in Iran, and it is made implicit that the clerk is not only fascinated with the director but is eager to involve him in his own illegal cinematic collusions, which he calls ‘cultural activity.’ Their conversation turns tense when the man begins introducing Panahi as his new partner.

The even keel of the film is broken up with sudden drama when a bloodied, injured man makes his way into the taxi, desperate to reach a hospital. Other passengers filter in and out here, several of whom we’re unsure of as being actors or not, often irritated with Panahi for not really knowing where he’s going, a bit of a running amusement concerning a director lost in the unpredictable adventure of his own fate. Running late to pick up his niece, Panahi drops off a set of old women jabbering about a fish they want to release back into the place they’d caught it, and he’s soon admonished by his ward for being late and daring to pick her up in a taxicab where her schoolmates can see her.

Panahi’s fascination with moral ambiguity becomes more prevalent as Taxi wears on. His niece, assigned her own filmmaking project at school, waves down a kid in the streets she’d been filming. She captured him taking money someone had dropped, a large bill he could easily have handed back to the man who didn’t notice. For the moral integrity of her film, she insists the young boy return the money, because, according to the guidelines for making a successful film per her class assignment, morally grey areas cannot exist and protagonists are not allowed to engage in criminal activity (amongst a bunch of other stipulations).

As per Panahi’s advice concerning the creation of storytelling he relates to an aspiring film student along the way, everything’s already been told or written, and you cannot look to the advice of others to create your narrative. Taxi (titled Jafar Panahi’s Taxi in the US, perhaps to differentiate it from those French comedies of the same name which inspired a US retread a decade ago) is a testament to Panahi’s considerable abilities despite the untoward restrictions against his right to artistic and creative expression.

The mere act of continuing to create cinema against these odds is an inspiration in itself. However, something which occurs in Taxi similar to his previous films in captivity is the continual reference to his past catalogue—eventually, will he be also referencing these cinematic endeavors of distress as nostalgically? And at what point will the recycling of his own themes become exhausted or even toxic?

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆