Leave Them to Heaven: Ben Hania Experiments with Form in Anguishing Roleplay

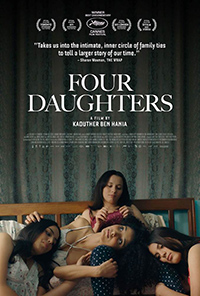

For her sixth feature, Four Daughters, Tunisian director Kaouther Ben Hania takes a peculiar approach in examining a familial tragedy. Olfa Hamrouni, the mother of the titular four daughters, appears as herself in a project by Ben Hania meant to be a simultaneous reenactment and documentary regarding the radicalization of her two eldest daughters, Rahma and Gofrane, both arrested after the US military bombarded an Islamist State hideout in Sabratha in 2016. Ben Hania also appears as herself, announcing to Olfa and her two youngest daughters, Aya and Tayssir, the three of them would be playing themselves in a series of reproduced moments alongside actors hired to portray their missing siblings. Another actor, Hind Sabri, is hired to play Olfa in sequences conjuring too much psychological or emotional trauma. While most of this seems like an outright terrible and overly complicated approach to a story which could easily be told as either a straightforward documentary or a feature narrative, there are compelling moments of catharsis in witnessing these three women who have been forced to come to terms with themselves and the actions of their kin.

For her sixth feature, Four Daughters, Tunisian director Kaouther Ben Hania takes a peculiar approach in examining a familial tragedy. Olfa Hamrouni, the mother of the titular four daughters, appears as herself in a project by Ben Hania meant to be a simultaneous reenactment and documentary regarding the radicalization of her two eldest daughters, Rahma and Gofrane, both arrested after the US military bombarded an Islamist State hideout in Sabratha in 2016. Ben Hania also appears as herself, announcing to Olfa and her two youngest daughters, Aya and Tayssir, the three of them would be playing themselves in a series of reproduced moments alongside actors hired to portray their missing siblings. Another actor, Hind Sabri, is hired to play Olfa in sequences conjuring too much psychological or emotional trauma. While most of this seems like an outright terrible and overly complicated approach to a story which could easily be told as either a straightforward documentary or a feature narrative, there are compelling moments of catharsis in witnessing these three women who have been forced to come to terms with themselves and the actions of their kin.

In 2016, Olfa Hamrouni’s two eldest daughters were arrested and imprisoned in connection with terrorist activities in their allegiance to the Islamist State. Seven years later, Olfa and her remaining children look back on their histories which contributed to this radicalization despite not being raised as religious, and what led all four of them to the path of religion despite various rebellious phases. Olfa emerges as a woman forced to protect her own mother and sisters in a fatherless household, and holding her own with their father by demanding agency over her body.

Although consistently interesting, since the format and how it unfolds suggests this family will be tumbling suddenly into trauma at any point in time, Four Daughters often remains questionable in its approach, eschewing a kind of subjectivity which might be necessary to lean into other aspects of the family. Media reports from 2016 suggest Aya and Tayssir were potentially more indoctrinated with the same beliefs as their sisters than is ultimately conveyed here, but there’s a steadfast articulation here in how they’ve come to stabilize themselves in the present while understanding and mourning the past. Olfa remains an intriguing mixture of contradictions throughout, warm and quite progressive on one hand and then judgmental and dismissive when confronted with another subject (specifically who has ownership of a woman’s body outside of her own). But watching Olfa with her two remaining children and their discussions about their ideals and beliefs is often fascinating.

Where the film never quite coalesces is through the segues into reenactments, where Hind Sabri has to step in as Olfa. It’s often more interesting to hear the sisters speaking than, say, a female-led exorcism in Libya, which seems to distract from certain logistical elements being neglected or obscured. These moments have a similar vibe to the 1994 television film starring Joan and Melissa Rivers as themselves, where personal catharsis doesn’t always translate for the audience. But at the same time, this odd juxtaposition of elements somehow allows for these womens’ voices to come through in a different way, the broken yoke of the film’s parameters allowing for an authentic sense of exploration. Although this isn’t always successful, and Ben Hania’s presence doesn’t feel necessary when she pops up, there’s a power to seeing Olfa and her two daughters reflecting resiliency after they’ve had years to process what happened and why. Footage of Rahma and Gofrane, the latter of which now has an eight-year-old-daughter, wearing niqabs in prison suggests a further reckoning upon their release in the future.

Reviewed on May 19th at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival – Competition. 110 Mins.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆