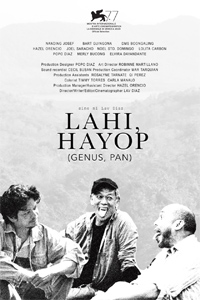

Three Amigos: Diaz Explores Featherless Bipeds in Latest Leisurely Expose on Baseness

Running time is always a point of contention when it comes the cinema of Lav Diaz, whose works, sometimes eight hours or more, tend to ensure to reception which arguably conveys the psychological effects of hazing on the minds of some cinephiles—to make it through such an endeavor in one sitting in a theater is, to some, the shiny gold participation star. As such, Diaz remains a divisive moniker amongst arthouse enthusiasts, which invites a fare share of snark from those who tend to dismiss him.Whatever one’s views about the necessity of editing and what a ‘proper’ running time for a narrative, standalone feature should be, Diaz remains a provocative fount of output, sometimes to his own detriment.

Running time is always a point of contention when it comes the cinema of Lav Diaz, whose works, sometimes eight hours or more, tend to ensure to reception which arguably conveys the psychological effects of hazing on the minds of some cinephiles—to make it through such an endeavor in one sitting in a theater is, to some, the shiny gold participation star. As such, Diaz remains a divisive moniker amongst arthouse enthusiasts, which invites a fare share of snark from those who tend to dismiss him.Whatever one’s views about the necessity of editing and what a ‘proper’ running time for a narrative, standalone feature should be, Diaz remains a provocative fount of output, sometimes to his own detriment.

Andres (Don Melvin Boongaling) is struggling to make ends meet, having to provide for his mother and sister as one of many miners endlessly searching for gold on the remote Hugaw Island, a place also known as Sleeping Turtle Island or “Dirty” Island, where crime and prostitution are rampant. The medication for his sister’s medication is expensive, keeping him mired in debt, while his colleague and fair-weather friend Baldo (Nanding Josef) gouges Andres on a deal they made which allowed for him to achieve employment in the mine. Their mutual friend and co-worker Paulo (Bart Guingona) seems to be able to assuage things, seeing as he has an intense history with Baldo, and the three men decide to partake in a boating expedition which allows them to return with goods. However, they request to be dropped off on the remote, dangerous end of the island so as to avoid paying exorbitant fees on their bounties. Along the strenuous way, we learn some terrible secrets about Paulo and Baldo’s past while Andres uses a distressing situation to benefit himself.

While featuring more of his signature pristine black-and-white photography, which feels about as indifferently edited as many a Diaz offering, Genus, Pan suffers from some of the same audio issues evident in his celebrated 2014 title From What Is Before, which took home the Golden Leopard at Locarno. Considering Diaz’s last stint in Venice, 2016’s The Woman Who Left, took home the Golden Lion, his inclusion in the Horizons sidebar with his latest seems a bit telling, perhaps more for being less compelling than an overall statement of the auteur’s craftsmanship.

Ostensibly, this is a miniature version of Joseph Conrad, with three men drifting into the jungle in search of profits. Not unlike an esoteric poor man’s Apocalypse Now (1979), everything plays out expectedly as three disparately connected men end their sojourn with tragic demise, the results of which are delayed due to Andres’ attempts to cover up what actually happened. Eventually, we’re shown what transpired, but the effects of this are already dulled by Diaz’s inability to really instill any sense of empathy for any of these characters, who he seems to hold in contempt, or at least like specimens wallowing in their own limitations rather than making any kind of supposedly noble choices which would likely elevate them based on their options at hand.

The message of Genus, Pan couldn’t be more heavy-handed, both in Diaz’s clear intentions and the even more clunky soundtrack. In one sequence, as the three men lounge in one of many scenes of extended rest, a discussion of a doctor being interviewed by a woman named Marian discussing how, with a few notable exceptions, most men’s brains are underdeveloped and closer to that of a chimpanzee, solidifies any intentions which the dialogue doesn’t hit one over the head with (“use your mind, not your emotions,” is a common scolding received by Andres).

Characteristics of this hypothesis are proven, in the opinion of this off-screen doctor, through all of man’s self-serving attributes, including manipulation and lying, something people like Mahatma Gandhi and Mother Theresa apparently weren’t capable of. Though it’s an interesting argument, about mankind’s continuing evolution, it’s a conversation which plays like sanctimonious propaganda (and not far off from silly explorations in something like Luc Besson’s Lucy, 2014). It also disregards the context in which certain people must resort to survivalist instincts and criminal activity as adaption. The ascension of Maslow’s hierarchy, and the development of philosophical ideals and self-actualization aren’t possible for humans unable to meet basic needs, which has more to do with mankind collectively than than a problem innate to humans making reprehensible decisions on an individual basis. In this scenario, Genus, Pan often seems demeaning towards it subjects rather than an enlightening treatise of the perpetual doom and stymied evolution of man’s capabilities or brain functionality. Socrates infamously referred to man as a ‘featherless biped,’ which, centuries later, seems to be the same assertion of Lav Diaz.

If the sound and production design are sometimes problematic, Diaz captures some of the worst performances of his oeuvre with all the gnashing, screaming and hysteria which visits these three men in the jungle. Later, moments of brutish violence are also choreographed ineffectively, further cheapening the film’s effectiveness. Baldo screaming at a monkey in a tree as way to introduce the exposition about his working alongside Paulo at a circus with a fellow performer, Clown, who we eventually learn they killed, is perfunctorily clunky, as is their own demise meted out in a reversal of fortune which seems to suggest Andres is nothing but their cruel kismet—who, in turn, will pay for his actions in a tepid, vicious cycle of crime and punishment.

Arguably, Diaz’s “musical” Season of the Devil worked, to some degree, because it didn’t take itself (at least entirely) as a serious exercise in tone or performance, while Diaz knows a thing or two about striking the right brooding sentiments (one wonders if working in color with 2013’s Norte, the End of History (read review) had forced a greater thought process in blending the narrative with the look of the film in ways which some of his black and white films don’t attempt). Overall, an interesting conversation piece, albeit one which casts judgment rather than sophistication.

Reviewed virtually on September 11th at the 2020 Venice Film Festival. Orizzonti (Horizons) Competition – 157 Mins.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆