Guards and Monsters: Costanzo Finds Humanity in Balanced Ratios

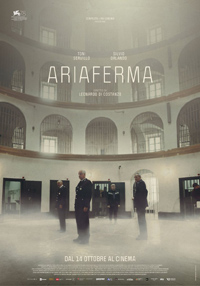

Utilizing the novel opportunity of how power wanes in the crumbling of an institution’s viability, Italian director and documentarian Leonardo di Costanzo presents a quiet microcosm in his third narrative feature, Ariaferma (The Inner Cage). Headlined by the sterling Toni Servillo as a gruffly benevolent captain of the guard, it’s a familiar if sometimes interesting presentation of the waning necessity of rigid sanctions hobbled by sloppy bureaucracy.

Utilizing the novel opportunity of how power wanes in the crumbling of an institution’s viability, Italian director and documentarian Leonardo di Costanzo presents a quiet microcosm in his third narrative feature, Ariaferma (The Inner Cage). Headlined by the sterling Toni Servillo as a gruffly benevolent captain of the guard, it’s a familiar if sometimes interesting presentation of the waning necessity of rigid sanctions hobbled by sloppy bureaucracy.

Although it also highlights how the proper care of inmates demands a well-balanced ratio of prisoners vs. guards, Costanzo leans heavily into forced connections to conjure emotional depths the narrative never authentically earns. Suggesting empathy between these two opposing camps is only possible under the almost impossible accidental conditions, at least as conceived here, it’s often a rather hokey tale about men opening their eyes to each other for the first time when rigidly designed futures are suddenly tenuous.

Mortana, a 19th century (imaginary) prison in a remote and unspecified part of Italy, has been decommissioned for use. Due to some bureaucratic snafus, a handful of the prisoners must stay behind at the prison while their paperwork for transfers is sorted. A handful of guards must also stay behind, led by their captain, Gaetano (Servillo). All visits and activities are suspended, with an outside company delivering meals. However, the prisoners are intensely unhappy with the food being served, and in this suspended, uneasy atmosphere, engage in a hunger strike. To avoid issues with the commissioner, Gaetano consults the unofficial leader of the prisoners, an ex-mafia boss known as Lagioia (Silvio Orlando), who insists he cook all the meals for the remainder of the current situation. Gaetano relents, leading to a relaxation in other various rules, allowing the men to develop more personable relationships.

Despite some committed characterizations from Servillo and Silvio Orlando, (both actors have been prominent in the Sorrentino stable), their “hard won” camaraderie never feels genuine. Begrudgingly, the mafia boss and the captain guard learn to respect one another, but there’s the queasy possibility this house of cards could all collapse into some kind of Assault on Precinct 13 scenario at any given moment (and one may keep wishing it would catapult itself out of maudlin lethargy by doing so).

Servillo is usually best served in his roles as an irascible playboy (The Great Beauty, 2013) or as an imposing criminal figure (Il Divo, 2008), and his Gaetano often feels a bit stiffly hewn, stuck in a good cop/bad cop dichotomy with a colleague played by Fabrizio Ferracane. Both sides seemingly unite over the care of an unfortunate youth, Fantaccini (Pietro Giuliano) who mugged and brutally beat a man, now facing a considerable prison sentence. A product of the foster care system, his anguish is painted in cliches, the worry of suicide supposedly genuine from both Gaetano and Lagioia. It’s this connectivity where Ariaferma often feels the most contrived, conjuring more interesting elements through the banality of Lagioia becoming a makeshift chef following the hunger strike born of intersecting frustrations.

Stuck mostly within the confines of the prison, an infrastructure in which the interior feels like a mausoleum, Costanzo’s limitations force a variety of obvious scenarios for dramatic finesse. Following the hunger strike and a catalyzing empathy for the anguished youth, there is the inevitable power outage, furthering even greater relaxation of rules. What feels like a last supper scenario unfolds, guards breaking bread with inmates and even sharing a bottle of wine. By the time the narrative reaches this point, the film feels as if its wheels are spinning. Inevitably, this transitory period comes to an end, with prisoners pilfered off to their next destination, the guards eventually to be assigned their next post.

Both bands of men, law enforcement and criminals, will continue to exist in this limbo required by captivity. What we’re likely meant to feel is the exhausting futility of the judicial system, the rippling cost of humanity reaching beyond those destined for such punishment. Ultimately, Ariaferma feels too obvious on all its fine points and only accomplishes an examination of ideas, forgoing the careful construction of characters which could have more powerfully underlined its intentions.

Reviewed on September 5th at the 2021 Venice Film Festival – Out of Competition. 117 Mins

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆