Paradis Regained: Albert Explores Thwarted Romantic Episode of Obscured Pianist

Austrian director Barbara Albert revisits 1770s high-society Vienna in her exploration of an attraction between a physician and his blind client in Mademoiselle Paradis. Like many portraits of European aristocracy, Albert wheedles the rigid pretension which dictated social interaction and ascension, picking up on the perspective which is perhaps the most complex—those on its confounding periphery.

Austrian director Barbara Albert revisits 1770s high-society Vienna in her exploration of an attraction between a physician and his blind client in Mademoiselle Paradis. Like many portraits of European aristocracy, Albert wheedles the rigid pretension which dictated social interaction and ascension, picking up on the perspective which is perhaps the most complex—those on its confounding periphery.

Decades before the Napoleonic Wars, with the city’s population on the rise, and musicians like Mozart (who was rumored to have written his Piano Concerto No. 18 in B flat major for the subject here) and Haydn in full swing while Austria’s Joseph II allowed press a greater freedom but censured the role of dancing in the opera, Albert focuses on a blind harpsichordist who rises to distinction thanks to her significant talents as a pianist despite her ailment. Her parents, however, are as equally mollified by her predicament as they are pleased to soak up the vicarious attention of their daughter’s achievements. When she begins treatment with a controversial doctor, whose findings were already being contested as suspicious or imaginary, a bond develops between the two which significantly changes the young woman’s outlook.

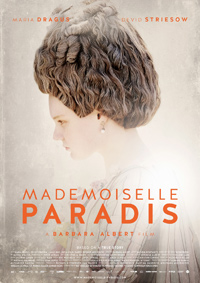

Blind since the age of three, Maria Theresia von Paradis (Maria Dragus), aka Resi, has managed to become a noted prodigy as a talented piano player. Her parents (Lukas Miko, Katja Kolm) are desperate to find a cure for their daughter, even though it’s her disability which makes her an automatic person of interest in her profession. When controversial physician Dr. Franz Anton Mesmer (Devid Striesow) takes an interest in treating her with his new discovery of invisible magnetic fluids which he believes he can use to direct Resi’s eyes to their restored abilities, the pianist finds herself desperately wishing to impress the man. Eventually, it seems Resi’s vision has slowly begun to return, while naysayers believe Mesmer’s tactics have only tricked her into believing what she’s experiencing is sight.

Albert, adapting from a novel by Alissa Walser, opens with a close-up on Maria Dragus in a powdered gray wig, her eyes contorting as she impresses a lackluster cadre of elitists in Habsburg. Her henpecking mother acts as a guide to control the facial expressions and movements she has no awareness of, while the murmuring crowd freely contemplates her looks. Forced to interact with a group of young women her age, Resi is told her eyes appear even worse after a rather extreme treatment which also caused her hair to fall out and purulent boils to overtake her body.

Drifting between these bits of vapid critiques and her parents’ less than loving methods of care-taking, it’s no surprise when Resi takes a liking to the kindly Mesmer, played with a self-important comportment by Devid Striesow. A commanding supporting cast awash in the ocher and amber glow of DP Christine A. Maier’s frames make Albert’s achievement even more impressive, each stuck in their bitchy, self-obsessed bubbles (look for Susanne Wuest of Goodnight Mommy, who appears with her own significant ailments and insanely styled hair as one of Mesmer’s patients).

But it is Dragus who remains the beating heart of Mademoiselle Paradis. Her face a complex cascade of differentiating shades of anguish, and she spins Resi into a highly empathetic characterization as a young woman both heartbreakingly lonely and unquestionably talented. Her desire to see (and impress her savior) is so desperate, she convinces herself she is beginning to regain the sensation of sight, which inadvertently throws the rest of her practiced rhythms perilously off-key. Dragus, who starred in Michael Haneke’s The White Ribbon, and as the key dramatic catalyst in Cristina Mungiu’s Graduation (2016), gives a formidable performance as Resi Paradis, and one which elevates the film above similar musical formulas (like the 2006 Chris Kraus drama 4 Minutes, a contemporary piano driven drama which briefly comes to mind).

A subtler romance than a similar dynamic as depicted in Alice Winocour’s 2012 debut Augustine, a period piece which also features a famed doctor and miracle achievements on a particular subject, comparable touches of the grotesque and carnivalesque still reside on the periphery of Mademoiselle Paradis in the requisite showings of Resi, forced to perform like a circus animal in order to maintain funding, public interest and enhance the reputation of her physician amongst his snobby colleagues (all men wishing to sabotage the other’s findings). Even if Mesmer’s an unabashed fake, he at least has the wisdom to recognize the errors of human nature (and logic) which allows him to operate as thus. “Eyes come no closer to the truth than the other senses,” he assuages Resi.

Albert mostly lets the archaic notions of the period speak for themselves, though takes gleeful pleasure in delivering countless gems of misogynistic rigor. “Our talents are held in the male cell,” contends Resi’s uncouth father. And while Albert prizes several intersectional motifs, (such as the act of seeing versus being seen, the odd mixing of science and art, money versus power, sight over sound, are all juxtaposed elements in Mademoiselle Paradis and a society laboring to reach enlightenment), its most unnerving statement is the division between men and women, and how Resi Paradis’ gender allowed for her to fall into the eager clutches of obscurity all the more easily.

Reviewed on September 8th at the 2017 Toronto International Film Festival – Platform Programme. 94 Mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆