Museum Hours: Wiseman’s Three-Hour Documentary Is a Riveting Essay About Narrative Construction

The latest entry in Frederick Wiseman’s tireless career project, which attempts to capture and reveal the systems and procedures within a vast variety of cultural and state institutions, is his most purely compelling and subtly provocative film in years. Focusing on the ins, outs, and in-betweens of the National Gallery in London, this is largely comprised of footage of museum visitors looking and listening, and tour guides talking and instructing; meanwhile, behind the gallery walls, a bureaucratic network of administrators, curators, and executives debate topics ranging from advertising and marketing strategies to crippling budget cuts. From every angle, stories ares being told, and histories being enforced. As always, Wiseman observes rather than imposing upon the goings-on, and he shapes his material in such a way that we can make our own judgments about what we see and hear — even it his own judgments inevitably make their way into the work, however subtly that may be.

Many who come to National Gallery will do so hoping for an opportunity to see a great number of high art masterpieces. With these expectations, the film could be a disappointment. There are countless shots of works by Turner, Da Vinci, Titian, and Michelangelo (among others), yet these each rarely last for more than five seconds, and Wiseman frames many of them so that the body of a visitor obstructs part of the painting. In this sense, one might feel as if Wiseman is doing something of a disservice to the art world’s grandmasters. But it is also something of a deliberate, even perverse strategy, and one that functions in two ways: first, we as viewers of the film haven’t enough time to construct a narrative around any given work, as we’re faced with a new image just as we’ve gotten a handle on what it is we’re looking at; second, it forces us to consider the works collectively rather than on each’s own terms — that is, we view them within a greater tradition and history.

As the film points out, there are dozens of virtually invisible factors at play in the museum that impose on the way we regard these pieces. This is observed in the application of gold leaf to the frames of certain paintings; in the grouping of the “Slavery Collection” into its own isolated wing; in the tour guides expounding on the histories of specific paintings, including the popular readings of certain gestures, compositional arrangements, and color choices in a given piece, while delivering the false promise that everyone’s own interpretation is unique and equally valuable (as if anyone can truly interpret something in his or her own way after having the institutional exegeses shackled to the brain); and it’s there in the unbelievably detailed and compelling look at the restoration process, including an explanation of a recent, state of the art reversible technique that allows restorers to touch up damaged and decayed paintings in such a way that their work is future-proof, so that new findings about the way a particular painting was originally “meant” to look can be more easily integrated into the work.

What it all amasses to is a portrait of the work of art in the age of narrative liberation. There isn’t much ambiguity regarding why Wiseman chose — in what one can assume will be his only film about a fine art institution — to focus exclusively on pictorial, representational paintings (every piece we see and hear about precedes Modernism’s abstracting impulses): these works are the most accommodating to storytelling, to the translation of the visual into language — that original sin of the human mind.

It is not coincidental that the film closes on a chapter on “Metamorphosis: Titian 2012,” the gallery’s exhibition of contemporary work that “draws on the powerful stories of change found in Titian’s masterpieces.” Of Titian’s “Diana and Callisto,”we’re told that “the meaning is in the gaps.” Ending the film somewhat cryptically on, of all things, a modern dance piece arranged by The Royal Ballet, Wiseman suggests his own affinities for such gaps, which, among other liberties, give the viewer the space to do his or her own interpretive heavy-lifting.

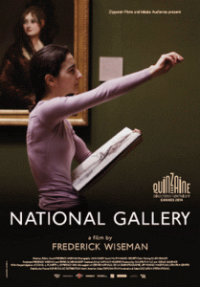

Reviewed on May 17 at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival – Directors Fortnight – 173 Minutes

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆