Songs from the Specious Floor: Larrain Imagines the Last Days of a Diva

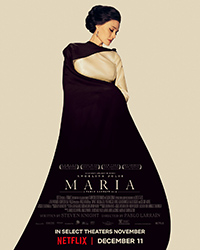

A penny for the thoughts of Maria Callas regarding Pablo Larraín’s glossy recuperation of her last week of life in Maria, the third in a series of high profile biopics of iconic women following 2016’s Jackie and 2021’s Spencer. Scripted by Steven Knight and lensed by Ed Lachman, the end result is a beautiful photo shoot for Angelina Jolie as a superficial approximation of the notoriously difficult diva, long considered by many to be the best opera singer whoever lived. Set during the last week of her life, it’s an elegiac reflection of a life told in various flashbacks as Callas slips into a sort of madness whilst suffering from impending heart and liver failure (which, of course, is not quite rightly reflected in the glamorous comportment of Jolie). About as much of an approximation as Natalie Portman was Jackie Kennedy or Kristen Stewart was Princess Diana, Larraín’s liberties aren’t so much considerable as unjustifiably inert, creating a final week which ends up feeling interminable in its posturing.

A penny for the thoughts of Maria Callas regarding Pablo Larraín’s glossy recuperation of her last week of life in Maria, the third in a series of high profile biopics of iconic women following 2016’s Jackie and 2021’s Spencer. Scripted by Steven Knight and lensed by Ed Lachman, the end result is a beautiful photo shoot for Angelina Jolie as a superficial approximation of the notoriously difficult diva, long considered by many to be the best opera singer whoever lived. Set during the last week of her life, it’s an elegiac reflection of a life told in various flashbacks as Callas slips into a sort of madness whilst suffering from impending heart and liver failure (which, of course, is not quite rightly reflected in the glamorous comportment of Jolie). About as much of an approximation as Natalie Portman was Jackie Kennedy or Kristen Stewart was Princess Diana, Larraín’s liberties aren’t so much considerable as unjustifiably inert, creating a final week which ends up feeling interminable in its posturing.

September 16, 1977. Maria Callas (Jolie) is confirmed as dead in her Parisian apartment at the age of fifty-three.The narrative backs up to one week prior, where, despite her addictions to various prescription medications, has decided to rehearse for a potential return to the stage. However, it’s been years since Callas last performed, the loss of her voice being public knowledge for nearly a decade. Her in-home staff (Pierfrancesco Favino, Alba Rohrwacher) are concerned, trying to keep her emotionally and physically afloat. High on her meds, she envisions a television crew interviewing her, wherein she reveals highly personal accounts of her past. Those memories still too raw and unprocessed plague her dreams. As the week progresses, a doctor confirms the obvious—Callas is in a fragile state, and performing again would certainly kill her.

Jolie, try as she does, is constantly distracting as Callas, constantly having to lip synch various bits of the singer’s greatest moments as well as perform the mimicry of a lost voice, sort of like the mime version of Florence Foster Jenkins (2016). Visualizing a traumatic event from youth, where her mother prostituted Maria and her sister to Nazi soldiers, it’s unclear when Callas evolved from her Greek heritage to become the green-eyed Jolie. Again, the mechanics of Larrain’s poetic license establish an impossible hurdle for either its performer or the film itself to conjure a feasible sense of its subject.

Most of Callas’ interactions take place in an immaculate home where she is tended to by Pierfrancesco Favino and Alba Rohrwacher as butler and housemaid, long accustomed to their employer’s mercurial demands. This is reflected in lightly caustic episodes where Callas requires Favino to move her piano back and forth whenever she wants to act out, despite his having a spine as ‘fragile as a twig.’

The framing mechanism, that of an imaginary interview, was also utilized in Jackie (2016), but feels supremely contrived this time around. Kodi Smit-McPhee (referred to as Mandrax, the name of the pills she’s endlessly popping) appears to ask questions providing most of the flashback sequences in her life, such as her initial meeting with Aristotle Onassis, her romantic partner of a decade who left her for Jackie Kennedy at about the same time she began to experience a diminished vocal capacity (and was also when she made her only film appearance as Medea for Pier Paolo Pasolini in 1969).

Anguish, guilt, regret and hurt pride are the underlying emotions suggested by these scenes, but unfortunately none of these moments reflect such intentions. Not even a late staged sequence with her sister (Valeria Golino) or a flashback to Onassis’ death bed allow for Jolie to rise above the excessively artificial design which usually allows for the suspension of disbelief required in any biopic (or, perhaps more appropriately here, deathpic). There are a few fleeting moments where Larraín aligns the star power of subject and performer, such as a snippet of Callas in The Mikado, a geisha costume reminiscent of another despairing moment with Jolie in 1998’s Gia. Her vague attempts at rehearsing for what seems to be her own benefit recalls the last days of Michael Jackson, whose exhausting physicality and penchant for medication also proved fatal.

Where Maria really pulls apart at the seams are interjections from an English speaking public, either to castigate her outside a cafe regarding canceled performances or to praise her at inopportune moments during domestic drama. Vincent Macaigne is on hand as a plaintive doctor trying desperately to give Callas the results of her bloodwork. Haluk Bilginer gives us a blustery caricature of Onassis, a collector of fine art and beautiful women, whose connection to Callas is overly referred to as loving, though the film forgets actions speak louder than words.

An imagined conversation with JFK is equally over baked, and the film’s sumptuous cinematography suggests it would be more believable on mute. Nowhere does the film dare to convey her (often) contradictory convictions regarding Marxists or gay men (though her relationship with Pasolini would prove transformational here on these fronts, at least in one emotionally intimate instance). Instead, Larraín shows us a dying diva who he wishes us to believe was a merely a fussy, beautiful talent dying with graceful elegance. Much like the 2024 Faye Dunaway documentary Faye (an actor who valiantly tried to direct and star in her own Callas vehicle), which mistook respect for sanitization in a rosy-tinted revisionist reflection, Maria may be a love letter to its subject, but it also does a disservice in declawing her.

Reviewed on August 29th at the 2024 Venice Film Festival (81st edition) – In Competition section. 123 Minutes.

★★/☆☆☆☆☆