Do You Really Want To Hurt Me?: Almodovar Finds a Talking Cure in Lavish Short

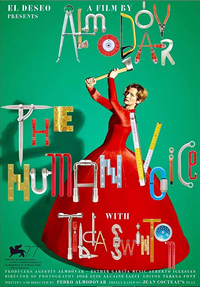

In more ways than one, Pedro Almodóvar tackling an adaptation of Jean Cocteau’s famous 1930 monologue play The Human Voice as the instrument for his English language debut marks a fascinating union of queer aesthetics. That Tilda Swinton is the well-heeled ganglion of raw nerves in this showcase of a woman who really is on the verge of a nervous breakdown is just the tip of its destructive iceberg.

In more ways than one, Pedro Almodóvar tackling an adaptation of Jean Cocteau’s famous 1930 monologue play The Human Voice as the instrument for his English language debut marks a fascinating union of queer aesthetics. That Tilda Swinton is the well-heeled ganglion of raw nerves in this showcase of a woman who really is on the verge of a nervous breakdown is just the tip of its destructive iceberg.

Cocteau originally intended the play as a platform for Belgian actress Berthe Bovy, but it would be resurrected on stage and screen multiple times since its inception ninety years ago. Roberto Rossellini first shot it in 1948 starring his lover Anna Magnani in the anthology film L’Amore, and then nearly twenty years later, Rossellini’s other famous lover Ingrid Bergman would perform the material for Ted Kotcheff in a 1967 television version. And Almodóvar’s own international breakout, 1988’s Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown was also an homage to this piece by Cocteau. But what stands out for Almodóvar’s mounting is perhaps the first real cinematic version which captures the intentions of the material, an eloquent vehicle written by a queer artist specifically for the talents of a bewitching, indomitable actress. As such, the material fits Swinton like an haute couture glove.

A woman (Swinton), alongside her restless dog, pensively regards the packed bags of her ex-lover, apparently waiting to be picked up. A suit lies stretched out on the bed, also waiting for its owner, a deflated metaphor for the man who should be there wearing it. As time passes, she runs one errand, buying an axe and a can of gasoline. Without a word, she makes fitful starts to busy herself, considers attending a party, then takes just enough pills to look like a suicide attempt if he arrives. But she’s revived, puts herself together again, sees she missed a call. In total, three days pass until finally, he calls again. At first anxious but relieved, the conversation tilts into her agitated emotions towards him, until she learns he never will be coming back and wishes to impart instructions for her assistance in shipping his belongings. Eventually, it sinks in. This will be the last time they speak.

As the opening credits indicate, this is adapted ‘freely’ from Cocteau’s play, further evidenced by sequences which feature Swinton outside of her lush apartment, shopping for an axe (with which, yes, she will wield on a symbol of her eclipsed love like Joan Crawford to the cherry trees), casting ambivalent stares at her dog all while set to a moody score from Alberto Iglesias. And then, the phone call she’s been waiting for comes to fruition, and we’re off on a roller coaster of emotional registers all while revealing a scattershot exposition of what’s going on. Draped in decadent reds by Sonia Grande’s provocative costume designs, Swinton wanders around her luscious apartment, which looks like tastefully decorated space meant as a tomb, and indeed, it’s the final resting place of a love no longer living. In one of many dazzling frames in her limited perambulations, cinematographer Jose Luis Alcaine positions her in front of a swooping green brocade – the comingling of jealousy and rage stewing within her.

Of course, it’s all about the delivery of the dialogue which sells the merits of The Human Voice. If Magnani and Bergman excelled at the anguish and despair, Swinton rocks from murderous to bitter to hellfire liberation. For every bon mot (“As if desiring someone wasn’t the oldest feeling in the world”) there’s a swath of banality for the performer to dig through believably, and there isn’t a second where Swinton doesn’t sing like an expertly tuned instrument of emotional discord. “But you don’t like sorry spectacles,” she facetiously tells him, the man who we never hear, towards the end of the conversation, before grappling with gasoline. It’s a journey which ebbs and flows believably, from her startling confession of “I’ve been afraid of hurting you,” segueing into actions which prove such fears have obviously retreated.

Besides the usual sumptuous expectations of an Almodovar production, his The Human Voice highlights the difference between showcasing an actress who is ‘involved’ somehow with its director versus a true homage to the talents of its iconic star. Whether it be Rossellini and Magnani as real-life lovers, Kotcheff and Bergman as a more traditional rendering of a woman’s plight under the male gaze, or even Edorardo Ponti directing his mother Sophia Loren in a 2014 version, it’s Almodóvar and Swinton who best formulate Cocteau’s vision as a woman speaking for herself, her eventual epiphany necessitating drastic chaos before rising like a phoenix through the ashes of dead love.

Reviewed virtually on September 24th at the 2020 New York Film Festival. Spotlight – 30 Mins

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆