The Last Word: Rúnarsson Sketches Mosaic of Modern Iceland in Varied Vignettes

Had each of the 56 segments of Echo, the third film from Iceland’s Rúnar Rúnarsson, been helmed by a different director, it would have been an omnibus fashioned into something like Reykjavik, I Love You. Instead, these unrelated single shot snippets of contemporary lives in Iceland around the Christmas season results in a sometimes touching, often austere portrait of the ups and downs of a particularly prime emotional occasion. Like a Roy Andersson film without the requisite absurdity, Rúnarsson abandons the linear narratives of his previous features Volcano (2011) and Sparrows (2015) and runs a gamut of narrative kernels (the central characters from those previous works could have fit into this panorama as well). Drifting in and out of these windows into sometimes charming, but often painful moments, like the ghost of Christmas present, once the film’s cadence is established the film takes on a soothing, meditative impression—though one in which it will be difficult to recall the wide variety of stories glossed over.

Had each of the 56 segments of Echo, the third film from Iceland’s Rúnar Rúnarsson, been helmed by a different director, it would have been an omnibus fashioned into something like Reykjavik, I Love You. Instead, these unrelated single shot snippets of contemporary lives in Iceland around the Christmas season results in a sometimes touching, often austere portrait of the ups and downs of a particularly prime emotional occasion. Like a Roy Andersson film without the requisite absurdity, Rúnarsson abandons the linear narratives of his previous features Volcano (2011) and Sparrows (2015) and runs a gamut of narrative kernels (the central characters from those previous works could have fit into this panorama as well). Drifting in and out of these windows into sometimes charming, but often painful moments, like the ghost of Christmas present, once the film’s cadence is established the film takes on a soothing, meditative impression—though one in which it will be difficult to recall the wide variety of stories glossed over.

Modern day Iceland collapses into a panorama of sparring visions at Christmas time, with characters whose connections to the past are informing, for better or worse, their relationship to one present moment in time. A snapshot of lives in motion, humanity is constantly influx, a mixture of devastation, concern, and excitement for a convergence into cultural tradition.

Echo begins with a house burning down. Just as we gather scant details about the farmer who’s recently inherited it, the scenarios switches to someone else, and so on and so forth, with no discernable connective tissue other than the country and seasonal time it’s set in. The real feat of the structure is editor Jacob Secher Schulsinger, who strings these moments together into its overall rhythm (Schulsinger has worked on several of Ruben Ostlund’s films, including Force Majeure and The Square, as well as Lars Von Trier’s The House That Jack Built and Amat Escalante’s The Untamed).

Some of these segments marry the banal to the sublime, such as a school choir segueing into female body builders. Other times, Echo is a roller coaster of unpredictable emotions, from a child calling 911 as violent parents rage in the background, to a grandmother trying out VR, to a mother arguing with her ex-husband on the phone concerning custody. Spatial relationship seems to be a recurring motif—those we are connected to most, whether they be intimates or financial institutions, are sometime farthest away from our clutches while we physically occupy space with strangers. In essence, as the title indicates, like the infamous Oread of Greek mythology, perhaps we are merely cursed with being able to repeat what was last said to us, while those in our line of sight, like Narcissus, are consumed only with themselves.

The film is a striking departure from Rúnarsson’s last two features, which are intimate narratives about a teen being sent from the city to the countryside to live with his grandmother in Sparrows to the harrowing debut Volcano, in which a gruff patriarch decides to nurse his wife following her stroke despite the interference of his children, who had been trying to get their mother to leave him. His latest is an ambitious, bird’s eye overview of human behavioral observations between moments of tumultuousness and familiarity, almost ethnographic in its attempt to present a modern portrait of objective interaction.

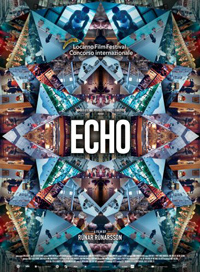

Reviewed on August 15th at the 2019 Locarno Film Festival – International Competition. 79 Mins.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆