The Body and the Whip: Strickland’s Sublime Homage to Erotic Cinema

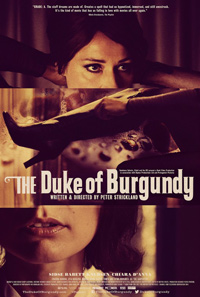

Beginning like something that should have been called Exploits of a Chambermaid, replete with a fantastically sumptuous rendering of a vintage title sequence lifted right out of the 1970s, Peter Strickland’s The Duke of Burgundy seduces us immediately. Much like his last film, the incredibly underrated Berberian Sound Studio, which was an homage to the giallo genre, his latest is a reconsideration of erotic exploitation cinema, where names like Jesus Franco and Jean Rollin garnered a notable cult following. But considering such influences, Strickland’s title is hardly cheap, though one would be remiss to deny a certain air of tawdry sentiment.

Beginning like something that should have been called Exploits of a Chambermaid, replete with a fantastically sumptuous rendering of a vintage title sequence lifted right out of the 1970s, Peter Strickland’s The Duke of Burgundy seduces us immediately. Much like his last film, the incredibly underrated Berberian Sound Studio, which was an homage to the giallo genre, his latest is a reconsideration of erotic exploitation cinema, where names like Jesus Franco and Jean Rollin garnered a notable cult following. But considering such influences, Strickland’s title is hardly cheap, though one would be remiss to deny a certain air of tawdry sentiment.

Evelyn (Chiara D’Anna) is a newly hired housekeeper. Making her way to her new employer, a strict, unfriendly woman named Cynthia (Sidse Babett Knudsen), it seems they already have a tense relationship that may have gotten off on the wrong foot—-until we get to a creepy reprimand that reveals this all to be a ruse. Cynthia is a burgeoning and considerably wealthy lepidopterist, and she’s begun a recent affair with Evelyn, a young woman whose masochistic tendencies have her obsessed with constantly improvising their repetitive ‘game plans,’ though this already seems to have the tendency to weary Cynthia. Little by little, their roleplaying begins a metamorphosis.

With the delightful music of Cat’s Eye gliding us through the opening credit sequence, The Duke of Burgundy opens with the haunting menace and style of some old Hammer studio production. As Evelyn arrives at her destination after a leisurely bike ride through an autumnal forest, we’re at first unsure of her relationship to the stone faced Cynthia. It becomes clear that something potentially deeper and darker is going on between them. Once discovering Evelyn and Cynthia are in a relationship, we’re not sure how long they’ve been together, only that they’re in the midst of a rigorous sadomasochistic role-playing stage of their union, though it seems this is actually scripted by Evelyn.

Unsure of time and place, though the multiple accents indicate somewhere diverse, the mysterious title almost seems more indicative of a locale, so named for a rare breed of butterfly that is only found in central southern Europe. When Cynthia isn’t engaged in the increasingly repetitive erotic machinations with Evelyn, she’s lecturing or attending a class with a small group of other professional biologists and etymologists (her own home eerily recalls the expansive collection of the killer played by Terence Stamp in The Collector).

As if taking a page from The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant, mannequins are mixed in with the audience of women participating at these gatherings—one of the many comical touches Strickland inserts in this fascinating study of a homosocial dynamic rarely interpreted seriously in cinema. Had this been released in the heyday of the era it recalls, this would have towered mightily over the queer scraps being tortured out of other genre films, like Aldrich’s The Killing of Sister George (1968) or Harry Kumel’s Daughters of Darkness.

Strickland seems to actually throw in a little Delphine Seyrig homage with a novelty manufacturer known as The Carpenter (Fatma Mohamed, who has appeared in all three of Strickland’s features), sporting a similar blonde bob, called upon to make a bed upon which one lover can sleep literally on top of the other, trapping the passive member underneath all night long.

More akin to the erotic atmosphere of Belle De Jour than the moody horrors of Jean Rollin, Burgundy is strangely beguiling and utterly intoxicating. Strickland once again casts D’Anna from Berberian Sound Studio, who has actual chemistry with co-star Sidse Babett Knudsen.

What gives the film its necessary depth is the level of sophistication these actresses bring to material that could easily have veered into camp or hysterical melodrama—at its heart, this is a highly stylized and provocative statement on the nature of relationships, the ebb and flow of guises. They make a compelling pair, as sensually photographed in the lush, astounding cinematography of Nic Knowland as are the plants, insects, animals and landscapes.

Each of Strickland’s films emerge as a rather sensory experience—you can almost smell Autumn in the air here, as we’re hypnotized amidst a flurry of slo-mo moth wings, cat’s eyes, rippling sheets, and moaning bodies. An opening credit concerning a perfume maker is appropriate, as The Duke of Burgundy has an unmistakable scent, look, and feel that’s utterly unique and unclassifiable—a rare cinematic breed of uncommon origin.

Reviewed on September 6th at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival – Vanguard Programme. 101 Minutes

★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆