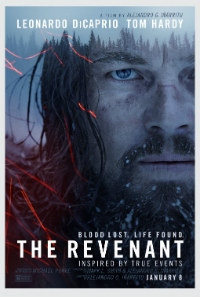

Essential Killing: Inarritu’s Remarkable New Thanksgiving Film

After winning a trio of Academy Awards last year for Birdman (which took home Best Picture, Director, and Screenplay), Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu returns in surprising succession with another English language masterpiece, The Revenant. Based loosely on a 2002 novel by Michael Punke, which documents a near mythical 1820’s cross country trek by fur trapper and frontiersman Hugh Glass, it’s perhaps most important to note Inarritu’s ‘looseness’ in adapting an already embellished ‘true account.’ Grueling, impressively detailed, and beautifully shot by Inarritu’s returning DoP Emmanuel Lubezki, it’s a ragged portrait of the American frontier, a period and time often glorified for the white, European perspective. Though the film sees a theatrical release during the high tide of awards season zenith, one wishes it had been ready in time to open on Thanksgiving weekend due to its barbed depiction of historical American gang wars, as Inarritu transcends the trappings of a mere survival revenge narrative to reach a more mystical, impassioned portrayal of hard won retribution.

After winning a trio of Academy Awards last year for Birdman (which took home Best Picture, Director, and Screenplay), Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu returns in surprising succession with another English language masterpiece, The Revenant. Based loosely on a 2002 novel by Michael Punke, which documents a near mythical 1820’s cross country trek by fur trapper and frontiersman Hugh Glass, it’s perhaps most important to note Inarritu’s ‘looseness’ in adapting an already embellished ‘true account.’ Grueling, impressively detailed, and beautifully shot by Inarritu’s returning DoP Emmanuel Lubezki, it’s a ragged portrait of the American frontier, a period and time often glorified for the white, European perspective. Though the film sees a theatrical release during the high tide of awards season zenith, one wishes it had been ready in time to open on Thanksgiving weekend due to its barbed depiction of historical American gang wars, as Inarritu transcends the trappings of a mere survival revenge narrative to reach a more mystical, impassioned portrayal of hard won retribution.

In 1823, frontiersman Hugh Glass (Leonardo DiCaprio) assists a hunting team through the uncharted American wilderness of Missouri as they gather pelts. Led by the fair-minded Andrew Henry (Domnhall Gleeson), the men are ambushed by a band of marauding Cree Indians, ruthlessly murdering white men they believe to have abducted the chief’s daughter Powaqa (Melaw Nakehk’o). Many of Henry’s men are exterminated as they flee via boat, leading to growing tension between trapper John Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy) and Glass, whose Pawnee son Hawk (Forrest Goodluck) inspires Fitzgerald’s deep seated rage he harbors against Native Americans. Following a brutal Grizzly bear attack, Glass is left incapacitated, and Henry demands three men stay behind to give the man a proper funeral when he expires. Hawk and the altruistic Jim Bridger (Will Poulter) offer their shares of a reward to Fitzgerald, who agrees to stay behind to make-up for the lost profit on the pelts. As the trio tends to the wounded Glass, best laid plans go awry.

The Revenant is specifically defined as “a person who returns,” usually in relation to a spiritual, ghostly realm, and the title provides a layered metaphor for what Inarritu’s film accomplishes. Opening on a sequence of beautiful landscapes which we come to understand as a site of carnage which claimed Glass’ wife and irreparably scarred his young son, Lubezki’s stunning camerawork recalls his work on several Terrence Malick titles, or perhaps the achievements of DoP Alexis Zabe with Carlos Reygadas in items such as Post Tenebras Lux (2012) or Silent Light (2007). Almost immediately, it descends into a bloody maelstrom rivalling the best of Peckinpah’s gruesome bouts of mankind’s brutality before it settles into the narrative’s main thrust.

Inarritu and Mark L. Smith’s adapted screenplay accomplishes an impressive job of crafting this test of human endurance into a swift, greatly detailed exercise. Its infrequent bouts of dialogue, many in Pawnee, are affixed with solemn observations, several of these in camp fire lit hours where its male characters reveal short bursts of detail concerning their lives. Ryuichi Sakamoto scores alongside Bryce Dessner and Carsten Nicolai with a repeated flourish of reverberating string instruments, underscoring the film’s funereal tone.

A painstaking, utterly captivating face-off with a grizzly bear is one of several arduous experiences on Glass’ odyssey, and eventually these travails become almost ludicrous, approaching the biblical level of Job. But Inarritu deftly captures the cruel and harsh reality of the landscape, and maintains an intimate violence between man and the elements, focusing on classic tropes of man vs. nature before descending into the inevitable direction of man vs. himself. But The Revenant is a revolving door of trading places, the ebb and flow of give and take. In essence, Glass is eventually assumes a similar perspective as the female grizzly he defeats, wearing her skin as his broken body heals on his painstaking journey. Crawling out of a makeshift grave, he symbolically dies and is later reborn from the carcass of a dead horse, all the while visited in his twilight moments by visions of his murdered wife and son. He dreams of a pyramid fashioned out of animal skulls, a three dimensional triangle as a symbol for mankind, whose power rests on his dependence to conquer, defeat, and kill all other forms of life. It’s exactly these moments of poetic interlude granting Inarritu’s new film a buoyant spirit, a grisly acknowledgement of humanity’s continued predilection for warfare, rape, and pillage.

Of course, there are more pointed motifs sprinkled throughout. Powaqa’s own father informs the traitorous French trappers of white man’s stealing of their land and a handful of juxtapositions mark the difference between the European tradition of taking without giving in return, assisting the narrative’s fashioning into the tightly coiled snail shell featured continuously throughout.

As always, Inarritu assembles a routinely sublime cast, from a number of known names (some who don’t even get to utter a line of dialogue, such as Lukas Haas, Kristoffer Joner, Javier Botet) to gracious supporting turns from up and comers (Domnhall Gleeson, Will Poulter). But no matter the final critical consensus of his works, Inarritu always seems to craft an excellent stage for his lead performers, and this is no exception.

Long overlooked at the increasingly vacuous Academy Awards circus yet consistently phenomenal is Leonardo DiCaprio, who spends a majority of the running time wracked and warped in considerable, excruciating pain. He gnaws raw buffalo meat, slurps fresh fish from the stream, and survives jumping over a cliff on horseback along with numerous occasions of inclement weather, all to track down the man who murdered his son. It’s a performance recalling Vincent Gallo in Skolimowski’s underrated Essential Killing (2010), a dialogue free exercise in survival, while its imperiled white man amongst the natives is a staple in many classics of the Western genre, particularly reminiscent of more solemn studies such as the Richard Harris headlined A Man Called Horse (1970) or Eastwood’s The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976).

As Glass’ antagonist, Hardy manages to make the monstrous emptiness of Fitzgerald quite empathetic, though it’s in the less sensational role. It’s difficult not to afford his character pity, bearing the butchered scalp from a past encounter with Native Americans and intent only on acquiring money to buy himself a bit of land in Texas. We’ve also seen Hardy in this vein before, a wide-eyed cuckoo a hair’s breadth away from insanity, and it makes an odd juxtaposition with DiCaprio’s naturalistic vibe. But despite the differences of creed and culture amongst the various tangents of the frontier, these are all perspectives, struggles, and desires understandably presented in The Revenant, where only those who maintain a bit of kindness and humanity in their hearts can reconcile past misdeeds in order to survive.

★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆