O Brother, Where Art Thou?: Benguigui Explores Fractured Cultural Identities in Meta Drama

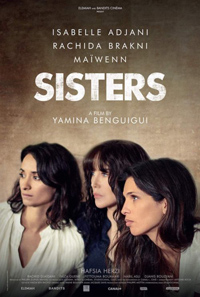

It’s been two decades since French-Algerian filmmaker Yamina Benguigui released her exceptional 2001 narrative debut Inch’Allah Dimanche, which explored the hardships of an Algerian woman forced to immigrate to France with her family. Largely autobiographical in scope, Benguigui returns to similar themes with a more complex narrative in her sophomore theatrical feature, Sisters, headlined by an impressive cast led by Isabelle Adjani.

It’s been two decades since French-Algerian filmmaker Yamina Benguigui released her exceptional 2001 narrative debut Inch’Allah Dimanche, which explored the hardships of an Algerian woman forced to immigrate to France with her family. Largely autobiographical in scope, Benguigui returns to similar themes with a more complex narrative in her sophomore theatrical feature, Sisters, headlined by an impressive cast led by Isabelle Adjani.

Metatextual and self-reflexive as it hinges on one immigrant family’s traumas and their navigation of fractured cultural identity, Benguigui straddles hybrids in a film examining catharsis through creative expression. Directly addressing the blurred lines of documentary and autofiction, Benguigui’s narrative is more successful as a formatting exercise than the social issue melodrama it consistently returns to. Showcasing the difficulties experienced by those tied to a particular cultural nexus through a familial microcosm of eternal discontent, there’s interesting character work from its three leads, each playing a woman resembling a shard of Benguigui’s own reality.

When youngest sister Norah (Maiwenn) is forced to move in with her mother Leila (Fattouma Ousliha Bouamari) after yet another failed employment opportunity, it seems to inadvertently cause a traumatic ripple effect. Norah blames her mother’s divorce from their father decades prior as the rationale for all their ensuing difficulties. Back when Leila left her abusive husband in Algeria to immigrate to France, both Norah and her younger brother Redah were kidnapped back to their homeland. After their father then abandoned them, Redah was never recovered. Eldest sister Zorah (Isabelle Adjani) has decided to explore this trauma through a stage play, casting her daughter Farah (Hafsia Herzi) as her mother. This appears to tear their family apart, with middle sister Djamila (Rachida Brakni), whose mayoral status and public persona also seemingly ruffled by the play, also in vehement disagreement with Zorah’s actions. Suddenly, the sisters learn their father has had a stroke, and the three of them travel to Algeria for a reunion in which they hope to discover potential news of their lost younger brother.

There are many parallels between Sisters and Maiwenn’s own recent directorial output, DNA, where a French-Algerian woman throws herself valiantly into exploring her cultural heritage upon the death of her father. Benguigui attempts a more comprehensive overview, traversing gender, culture, and economic opportunity. Immediately, we learn a traumatic abduction of Norah and her younger brother Redah has defined their reality in France, seeing as their brother was still never returned to them despite their mother’s appeals to both the French and Algerian governments. Norah in particular is saddled with a sense of guilt. The rift between the three sisters and their mother explores dramatic reactions to their differing attachment styles, and Adjani’s Zorah plays like the referee between her younger siblings. Her formulation of a stage play based on her childhood, while meant to explore a universality in these experiences, shakes up the family considerably.

Too conveniently, their estranged father’s stroke sends all three back to Algeria in an attempt to either reconcile or discover what happened to their brother. The reunion doesn’t go as any of them could anticipate, but it’s where Benguigui really rips into their anguish, staged brilliantly in a violent stand off between Norah and Djamila in a hospital elevator. One wishes this sort of energy was apparent more frequently, as the first half of the film mulls the necessity of Zorah expelling her familial demons through creativity in ways her family cannot relate.

Adjani is interesting here, arguably the main stand-in for Benguigui as an artist (Brakni’s Djamila tends to reflect the director’s familiarity in French politics), and surprisingly level headed considering the raw emotional potential she’s best known for (Possession; Camille Claudel). Zorah’s thorny ambivalence is entertaining in its own way, frustrated by her family, including daughter Farah, played by Hafsia Herzi. Interestingly, Farah segues between the stage play and intense flashback sequences of her grandmother’s experiences in the Algerian War, including the search for young Redah. Largely, these flashbacks seem to be in the mind’s eye of Zorah, but it creates an interesting ripple effect across periods.

Although Benguigui doesn’t answer any of the questions the film poses, such as where women like Zorah and her sisters could feel they belong, it expresses the need for such representation, in a specific vacuum wherein cultural integration was or is not entirely possible in France while their native country remains dismissive of their experiences.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆