Palo Alto 2: Demeestere Crafts Franco’s Prose for Portrait of Preadolescent Angst

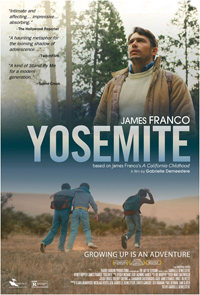

Director Gabrielle Demeestere adapts James Franco’s A California Childhood for her directorial debut, Yosemite, a mid-1980s set triptych on three young boys in the suburban climes of Palo Alto. If this sounds a bit familiar, it may be because Demeestere is the second woman director to adapt Franco’s prose for a debut, following Gia Coppola’s 2013 title Palo Alto, based on Franco’s earlier short story collection Palo Alto Stories. Franco also happens to appear as a peripheral character in both. Demeestere’s film premiered at the 2015 Slamdance Film Festival, and probably won’t be assisted by the presence of Franco during its limited theatrical release due to the actor/writer/director’s multiple cinematic offerings during any given period. Still, Demeestere scores points with this low-key slow burn which features naturalistic performances from its three young leads (Coppola distractingly padded her film with the relatives of celebrities—though one appears here, as well).

Director Gabrielle Demeestere adapts James Franco’s A California Childhood for her directorial debut, Yosemite, a mid-1980s set triptych on three young boys in the suburban climes of Palo Alto. If this sounds a bit familiar, it may be because Demeestere is the second woman director to adapt Franco’s prose for a debut, following Gia Coppola’s 2013 title Palo Alto, based on Franco’s earlier short story collection Palo Alto Stories. Franco also happens to appear as a peripheral character in both. Demeestere’s film premiered at the 2015 Slamdance Film Festival, and probably won’t be assisted by the presence of Franco during its limited theatrical release due to the actor/writer/director’s multiple cinematic offerings during any given period. Still, Demeestere scores points with this low-key slow burn which features naturalistic performances from its three young leads (Coppola distractingly padded her film with the relatives of celebrities—though one appears here, as well).

Three separate segments focus on fifth graders Chris (Everett Meckler), Joe (Alec Mansky) and Ted (Calum John), classmates growing up in suburban Palo Alto in the autumn of 1985. Chris takes a trip to Yosemite National Park with his younger brother and estranged father (Franco), a recovering alcoholic. They accidentally get lost for a bit and stumble upon something creepy in the woods. At the same time, Joe is having difficulty dealing with the loss of a loved one, isolating himself from best friend Ted and engaging in rebellious behavior, such as shoplifting. Joe makes an older friend, Henry (Henry Hopper, son of Dennis), who invites him over to read comic books and escape from the world, although Henry’s intentions are unclear. Meanwhile, Ted begins bullying Joe at school to elicit some kind of response.

Menace and a subdued foreboding linger throughout Yosemite, quite strikingly in its first two chapters where a young protagonist interacts uneasily with a dubious adult figure. Demeestere’s decision to name the project after the famed tourist attraction suggests not only the inherent beauty of nature’s significant visual endowments but also the obliviousness towards the human subjects who are part of it—these moments are both detrimental to the emotional development of these young boys but also inherently meaningless in the larger picture. When Chris and his father stumble upon the eerie vision of a skeleton burning brightly in a small field fire, discomfort and distrust set in, and it primes us to imagine the worst. Joe’s budding friendship with an emotionally immature man in the second segment has all the requisite red flags of a pedophilic scenario, but Demeestere dances around the obvious.

Events becomes a bit more banal in the third sequence, where Ted’s struggle to understand Joe’s emotional baggage centers the narrative and unites the three boys in a violent scenario involving a handgun and a threatening mountain lion (which also recalls Cam Archer’s Wild Tigers I Have Known, 2006). It’s here where various tidbits frame the time period most distinctly, young boys quoting Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), and a VHS copy of The Dark Crystal (1982) used an excuse to bring friends back together. Train tracks and the promising sanctuary of convenience stores elicit a melancholy echo of those hazy, aimless days at childhood’s inevitable end in Yosemite, with DP credits split between Bruce Thierry Cheung (a fixture in Franco’s troupe) and Chananun Chotrungoj for a simplistic but observant rendering.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆