The Safety of Objects: Larrain Revisits Traumatic Chapter of Iconic First Lady

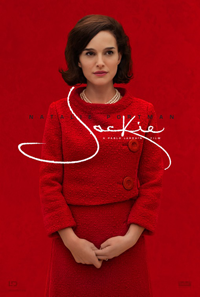

There have been very few First Ladies either before or after Jacqueline Kennedy who succeeded in achieving the same cultural iconicity—and those who have (Obama, Clinton, Roosevelt) were not subjected to something like the traumatic chapter which transpired on November 22, 1963 when President John F. Kennedy was infamously assassinated during a motorcade through Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas. The tragedy captivated the nation, as did the ensuing funeral and Jackie Kennedy’s exit from the White House as Lyndon Baines Johnson succeeded the presidency. Curiously, Chilean auteur Pablo Larrain revisits this period through the perspective of the fashionable figure in his English language debut, Jackie, which sees Natalie Portman wade through morose measures as the eponymous figure in the days directly following the death of her husband as she recounts the experience to a journalist. Noah Oppenheim’s screenplay (a significant departure from the likes of his previous credits, Allegiant and The Maze Runner) utilizes flashbacks and creative reconstructions to paint a portrait of a woman at the center of a significant historical moment, and one partially responsible for the fantastical public fabrication of a family and an era forever references as Camelot. The title could potentially be misleading, since this isn’t a biopic as it begins shortly after the death of her husband, allowing for some candid characterization as she opens up to a reporter to share her experiences on the day her husband was shot and the subsequent controversial funeral plans.

There have been very few First Ladies either before or after Jacqueline Kennedy who succeeded in achieving the same cultural iconicity—and those who have (Obama, Clinton, Roosevelt) were not subjected to something like the traumatic chapter which transpired on November 22, 1963 when President John F. Kennedy was infamously assassinated during a motorcade through Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas. The tragedy captivated the nation, as did the ensuing funeral and Jackie Kennedy’s exit from the White House as Lyndon Baines Johnson succeeded the presidency. Curiously, Chilean auteur Pablo Larrain revisits this period through the perspective of the fashionable figure in his English language debut, Jackie, which sees Natalie Portman wade through morose measures as the eponymous figure in the days directly following the death of her husband as she recounts the experience to a journalist. Noah Oppenheim’s screenplay (a significant departure from the likes of his previous credits, Allegiant and The Maze Runner) utilizes flashbacks and creative reconstructions to paint a portrait of a woman at the center of a significant historical moment, and one partially responsible for the fantastical public fabrication of a family and an era forever references as Camelot. The title could potentially be misleading, since this isn’t a biopic as it begins shortly after the death of her husband, allowing for some candid characterization as she opens up to a reporter to share her experiences on the day her husband was shot and the subsequent controversial funeral plans.

As far as performance goes, Natalie Portman gives a moderated impression of a woman famed for her mannerisms and a particular way of speaking. Her command of Jackie’s distinct accent, a Boston emphasis gilding the pronunciation of words uttered as if they’ve been transported through a more robust, remote dimension, is commendable (and perhaps noticeable to the point of distraction), but works best when filtered through the recreation of her fuzzy black and white tour of the White House in 1961. A woman accused of spending frivolously for her famed re-decoration of the presidential quarters, her gravitation towards objects and their ability to convey a historical legacy is repeatedly referenced in Larrain’s film, documenting her greatest achievement during the intense period by demanding a funeral march rather than a more secure motorcade for JFK’s funeral.

Portman’s performance will most likely be pegged as a frontrunner for Best Actress this awards season, but the mannered, sometimes overly polished performance is at times too refined to elicit emotion, the performer overwhelming her own subject. Instead, an expressive score from Mica Levi (Under the Skin, 2013) rivals Portman’s presence as the film’s most emotionally pertinent aspect. Despite sympathetic possibilities, her characterization in Jackie gets overwhelmed by the magnitude of her situation, as we’re treated to a woman preoccupied with incredible morbidity, juggling material and spiritual needs in the aftermath of a tragedy which quickly and dramatically uproots the lives of her and her children. Fantastically glossy close-ups from DP Stephane Fontaine (Elle) hint at a pained martyrdom, but always remain exquisitely superficial. Jackie’s contributions to her husband’s kingdom are certainly documented here, but the significance isn’t always proportional.

Several film treatments have recreated this period and this particular week in meticulous detail (Oliver Stone’s JFK, Peter Landesman’s Parkland). But as for Jackie’s perspective, few films have afforded her such a wide berth. There have been many portrayals of how she was an influential figure (like Michelle Pfeiffer’s avid fan in Love Field, or Parker Posey’s crazed one in The House of Yes), while even the woman’s relatives have ascended to iconicity (the extended family making up the subject of the Maysles’ Grey Gardens). In part, like the title suggests, her shadow looms significantly over the mise-en-scene, reflected in the limited characterizations of her co-stars, like Peter Sarsgaard as Bobby Kennedy, or Greta Gerwig as her sympathetic aid. A bit more reflective are the exchanges with John Hurt as a priest, and Billy Crudup as a testy journalist unafraid to engage in a subtle battle of wills with a woman who announces her authority and control before he can even get a foot in the door.

Larrain, who has meticulously detailed chapters from Chile’s history and its politics for his past several features (including another period piece from this year, Neruda) makes an interesting choice to tackle Jackie Kennedy’s most traumatic ordeal, but ultimately yields little surprises about a woman who, according to this film, was very much in control of handling her own public image.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Reviewed on September 14th at the 2016 Toronto International Film Festival – Platform Programme. 91 Minutes.