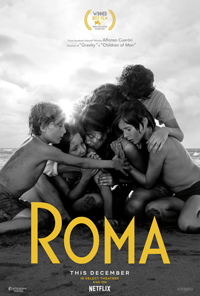

Going Home Again: Cuarón Aces Return to Mexico with Autobiographical, Intimate drama

From one woman reaching the shore to another going back to it, from the future to the past, from a virtuoso director to a silent kid in the background who is growing up in 1971 Mexico City: this is the quiet dive, nostalgic yet lucid, that Alfonso Cuarón takes into his own childhood. Roma, coming five years after Gravity (review), is the long-announced return to a more personal, intimate scale of filmmaking for a director who in the last decade has been defined mostly by high-concept set pieces and outsized technical skills.

From one woman reaching the shore to another going back to it, from the future to the past, from a virtuoso director to a silent kid in the background who is growing up in 1971 Mexico City: this is the quiet dive, nostalgic yet lucid, that Alfonso Cuarón takes into his own childhood. Roma, coming five years after Gravity (review), is the long-announced return to a more personal, intimate scale of filmmaking for a director who in the last decade has been defined mostly by high-concept set pieces and outsized technical skills.

The more alluring point, however, is seeing what Cuarón’s idea of ‘personal’ is: Roma’s study of an upper-middle class family shows an entirely peculiar point of view; neither a coming-of-age story, nor a committed dissection of class politics, it firmly focuses on Cleo, the family’s live-in maid, and it glides over many of the traditional staples of the family drama despite leaving in its final minutes a strikingly coalesced impression of one.

Shot by Cuarón himself in a textured, profound black and white, the film is one and all with its main location, a two-story villa in the Roma district of the city. We find our way there through the perfectly-recreated traffic noise on the street outside, then get acquainted with the main driveway, too narrow for the big family car (the scene that introduces the father is an exaggerated affair of faux tension and anticipation as the car just barely makes it inside, in an exquisite critique of pompous masculinity that is played for laugh while the rest of the family awaits in suspense in front of the door), and soiled at an impressive rate by the dog’s excrements. Much is made throughout the film of this visual motif, and it’s a testament to the lyrical but comfortable familiarity of the piece that the tone remains always just right.

While Cleo (played by non-professional actress Yalitza Aparicio with the kind of wide-eyed passivity that somehow becomes engrossingly full of agency) cleans up and folds the laundry, the four kids and their mother go about their increasingly difficult life, with an absent father upsetting the placid rhythm of the past. And it’s those rhythms that truly mark Roma as its own thing: the serenity of multiple inconsequential afternoons in the house is accompanied by undulating, soothing horizontal pans from one corner of the room to the other, often drawing trajectories and connecting lines between the kids and their mother, or between Cleo and the kids. Thematically, this domestic diorama (the work of production designer Eugenio Caballero is meticulous and exhausting in volume) also deepens the keen observation of a relationship that goes back and forth between the professional and the personal, often in unexpected ways.

Things change when members of the extended family venture outside on the streets of Mexico City. Here, Cuarón favors tracking shots that decisively highlight movement, or impeccably-staged, vast crowd scenes. And yet even when he ends up echoing shots from Children of Men, like in the impressive reconstruction of the Corpus Christi massacre that caused some 120 victims, there is a previously unseen delicateness to the proceedings. Without ever assuming the directly autobiographical point of view of the children, he manages to muffle the action in a veil of compassionate detachment, so it never feels as massive as it is. In a way, Roma is the vehicle for Cuarón’s greatest ever technical trick – intimacy as the ultimate form of spectacle.

Reviewed on August 31st at the 2018 Venice Film Festival – In Competition. 135 Mins.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆