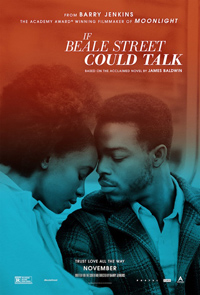

I Can Feel the Beale: Jenkins Does Justice to Classic Baldwin Novel

Following his history making Best Picture winner Moonlight, stakes are set high for Barry Jenkins’ third feature, which is also a major milestone as the first English language adaptation of a James Baldwin novel with If Beale Street Could Talk, originally published in 1974 (but previously adapted in 1998 by Robert Guediguian as Where the Heart Is). It’s safe to say Jenkins rises to the occasion, introducing the film with an explanation from Baldwin himself explaining the importance behind the meaning of Beale street, where the blues and jazz were born, giving voice to the lamentation of the Black experience in America, and the continual blatant and systemic racism which continues to be a defining reality. A subtle reflection on the conditioned resignation and hopelessness regarding the American legal system, Jenkins reflects the same poetic dissonance using the same location as Langston Hughes’ famed poem “Harlem,” which poses the same prescient question of the families irrevocably affected here—what happens to a dream deferred?

Following his history making Best Picture winner Moonlight, stakes are set high for Barry Jenkins’ third feature, which is also a major milestone as the first English language adaptation of a James Baldwin novel with If Beale Street Could Talk, originally published in 1974 (but previously adapted in 1998 by Robert Guediguian as Where the Heart Is). It’s safe to say Jenkins rises to the occasion, introducing the film with an explanation from Baldwin himself explaining the importance behind the meaning of Beale street, where the blues and jazz were born, giving voice to the lamentation of the Black experience in America, and the continual blatant and systemic racism which continues to be a defining reality. A subtle reflection on the conditioned resignation and hopelessness regarding the American legal system, Jenkins reflects the same poetic dissonance using the same location as Langston Hughes’ famed poem “Harlem,” which poses the same prescient question of the families irrevocably affected here—what happens to a dream deferred?

Tish (KiKi Layne) is only 19, but well on her way to growing up fast. Pregnant by her childhood sweetheart Fonny (Stephan James), Tish finds herself suddenly alone when he is arrested for an erroneous charge of rape and on his way to prison for it despite considerable evidence suggesting the contrary. While her supportive parents (Regina King, Colman Domingo) do their best to support her, Fonny’s parents (Aunjanue Ellis, Michael Beach) quickly give up hope. As the proverbial noose tightens around Fonny’s future, their love and commitment to each other is tested.

Jenkins, who has professed a love for Wong Kar Wai, again reflects these passions through Moonlight DP James Laxton, who delivers several exquisite close-ups, such as Layne during a post-love making reverie, or a fantastic hold on Regina King as she unfurls her hair from underneath a wig, mustering the courage for a confrontation which should be wished on no one. Characters forced to encounter inner demons are caught in profile, the camera hovering at uncomfortable side angles, unable to face their pain head on (such as a formidable exchange from Bryan Tyree Henry, prophesizing the doom Fonny himself will soon experience, or Michael Beach confessing his anguish).

And it’s in these significant supporting roles where Jenkins finds unexpected significance. Regina King is masterful as Tish’s mother, a woman who must shoulder the weight of being a black woman in a white man’s world whilst absorbing the responsibilities of others who have buried their head in religion or simply lost their hope to cruel realities. King’s casting also recalls the troubled romance in Poetic Justice (1993), the John Singleton classic in which she was a supporting character. Set two decades after Baldwin, little had changed then or now in America’s treatment of young black men. Like that earlier film, how people of color are kept down, kept divided, and kept desperate is a central conceit here, and one which should significantly resonate.

Besides King, Colman Domingo is a generous breath of levity in an exercise which could have easily sank into miserabilism in the right hands—and yet, the focus maintained here with his presence is that of love, acceptance, and sacrifice. While most of the buoyant supporting players of Moonlight were overlooked in favor of the flashier, aggrandizing roles when it came to awards season, perhaps the opposite will become true of Beale thanks to the generous display of warmth and subtlety from King and Domingo, both deserving of acclaim for their performances.

Newcomer KiKi Layne is a fitting choice as the naive protagonist of Baldwin’s prose, which is kept wonderfully intact thanks to Jenkins’ use of her omniscient narration, while Stephan James is the right balance of boyishness cut short by anguish as Fonny. In the outer limits of the supporting cast, which includes the likes of Dave Franco and Diego Luna, mention should be made of the lone sequence featuring Aunjanue Ellis as Fonny’s Bible-toting mama. Struck down violently while cursing Tish’s unborn child, she manages to be as empathetic as she is toxic, an obvious example of Baldwin’s finer subtexts on the opiate of the masses as well as a victim of circumstance.

While Beale is not focused on grand, dramatic scenes, Ellis conjures a whip of electricity in her solo moment, which reverberates painfully. And what if Beale Street could talk? If it could, it would be from behind a thick pane of glass to endure whatever was said could continue to be disregarded, demeaned, and disparaged.

Reviewed on September 10th at the 2018 Toronto International Film Festival – Special Presentations Programme. 117 Mins.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆