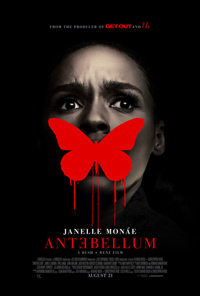

(Re)Birth of a Nation: The Past is Our Present in the Auspicious Debut from Bush & Benz

Genre filmmaking has always been the most fruitful forum in which audiences can experience the superficial elixir of both entertainment or catharsis alongside subtexts which are usually watered down or avoided (arguably, impossible) in presentations of the reality of our past or present. A case in point is a formidable debut from directors Gerard Bush and Christopher Renz with Antebellum, a horror film which uncomfortably marries past and present to showcase an America which, in shirking atonement for its original sin, has instead let it run rampant like an infection (or a virus, if you will) so symbiotic with our conditioned understanding of cultural heritage we have normalized an inherent evil in ways which seem irrevocable.

Genre filmmaking has always been the most fruitful forum in which audiences can experience the superficial elixir of both entertainment or catharsis alongside subtexts which are usually watered down or avoided (arguably, impossible) in presentations of the reality of our past or present. A case in point is a formidable debut from directors Gerard Bush and Christopher Renz with Antebellum, a horror film which uncomfortably marries past and present to showcase an America which, in shirking atonement for its original sin, has instead let it run rampant like an infection (or a virus, if you will) so symbiotic with our conditioned understanding of cultural heritage we have normalized an inherent evil in ways which seem irrevocable.

Slavery, of course, is this sin, and perhaps no other cinematic endeavor has so unflinchingly or effectively demonstrated the insidiousness of systemic racism as the reflection which keeps us collectively ill.

Eden (Janelle Monáe) is a slave on a reformation plantation who has just tried to escape her captors. Brought back after capture, she’s beaten and branded, while bearing witness to the violent fate of another couple who disobeyed the white masters (Jack Huston, Eric Lange). A new shipment of slaves arrives, and one of the women (Kiersey Clemons) recognizes Eden and she urges her to assist in helping her escape, but Eden is adamant about waiting for the right time. Suddenly, the perspective shifts to modern day. Veronica Henley (Janelle Monáe) is a successful author, promoting her new book Shedding the Coping Persona. Invited to a symposium in New Orleans, she leaves behind her husband and child in Virginia. Upon arrival in the city, everything seems to be just a little bit off. After having drinks with old friends (Gabourey Sidibe, Lily Cowles), the reality of her earlier nightmare is revealed in all its unthinkable terror.

A true examination of what the desire to “Make American Great Again” really means is here, crystallized in a horrific genre exercise which, had it been released under less strenuous circumstances might have been easily written off as hyperbolic, maybe exploitative. After all, there was a whole line of rational which asserted we were living in a ‘post-racial’ America when President Barack Obama served two consecutive terms.

And we’re used to seeing our depictions of slavery as finely wrought dramas, usually films which feature fine performances, often courting awards recognition at the end of every year—itself a euphemism for how a largely white voting body displays its comfort with Black representation in cinema, arguably an exorcism of guilt (last year, Cynthia Erivo as Harriet Tubman was the only Black person to receive an Academy Award nomination in an acting category, this despite the usual bevy of Black men and women who gave buzzy performances).

Outside of the confines of a serious melodrama, usually featuring sympathetic whites to ensure our awareness there have always been a few who have existed, the depiction of slavery seems exploitative, triggering, and in poor taste. And yes, the first forty minutes of Antebellum could be described as such, on a first viewing, should you make it this far—for who, after all, wants to watch Black bodies beaten, raped, tortured and incinerated in an exhausting year when such has become the continual cultural conversation in daily news headlines? As such (spoiler alerts ahead)—the brilliance of it won’t register until the third act when it’s confirmed that Eden is Veronica and the timeline of the film has been interrupted for enhanced dramatic effect.

Systemic racism is the new slavery, but our inability to eradicate it by dismantling our criminal justice system or our education system or our health system means slavery has been and is here to stay, in some shape, way or form. Slavery is a state of mind, and if the events of Antebellum invite derision or disbelief as to how such a scenario could ever happen…well, we’ve been there before. We still allow homegrown terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan to practice, preach and gather. How is this not a logical, albeit slippery slope? But then again, the safety of genre does allow for a suspension of disbelief.

That said, every singly minute and each interaction peeks into a confounding display of microaggression, as evidenced by every exchange with Monáe and another white character. Sure, they aren’t all terrible, and the best-case scenario (Lily Cowles) still manages to showcase the obliviousness inherent to white privilege. It’s a white-hot (pun intended) metaphor for how America isn’t operating with broken systems but willfully using such systems as tools of oppression. As upsetting as it is to see, what is happening on the Antebellum plantation is a physical embodiment of the conditioned mind frame established for people of color in America. As the directors’ statement reflects prior to the film, theirs is meant to be a film “of and for this moment.” Outrageous? Not really. To discount Antebellum or dismiss its provocations is just deflecting the conversation it generates, whether one likes it or not. If Peele’s Get Out (2017) formulated the visual of the sunken place, Antebellum positions this as the widespread law of the land.

Much like M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village (2004), which isn’t an altogether perfect film but certainly far ahead of it’s time, white flight was brought to a sort of logical progression. These were the white folks who simply wanted to go back to better times in isolated white environments. Their xenophobia limited themselves and the futures of their loved ones. In Antebellum, we have another facet of the racist white, those who want to control and dominate. If you go back and watch it, all those troubling red flags in the first forty minutes make sense, are even more troubling (a speech at a dinner about ‘the sapphires’ at their disposal, for instance, confirming the affluent, strong Black women being targeted).

The collapsing of our racist heritage with our ongoing racist ideologies is the full-blown extension of something also recently portrayed in the equally important art-house offering All the Dead Ones (2020) from Marco Dutra & Caetano Gotardo. These are issues which can be explored and acknowledged, but, alas, catharsis is neither to be found nor to be had.

Cinematographer Pedro Luque (Don’t Breathe, 2016; Body Cam, 2018) assists in channeling an overwhelming atmosphere of dread. An opening sequence set in slow-motion to a stunning soundtrack (featuring Monáe collaborator Nate Wonder and Roman GianArthur Irvin as composers) is an opening shriek of pain and terror which only gets stronger—as well as a wonderful resurrection of “Warm Leatherette” originally released by The Normal in 1978 (before Grace Jones sunk her teeth into it). Monáe is joined by a game supporting cast, from the violent racists played by Jack Huston and Jena Malone to Gabourey Sidibe (whose characterization as Dawn also reveals significant facets about behaviors decried in Black women but deemed acceptable by white counterparts).

The film opens with a quote from William Faulkner, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past,” taken from Requiem for a Nun (1951), the sequel to his controversial Sanctuary (1931), filmed as The Story of Temple Drake (1933). But as far as what Bush and Renz have created with Antebellum, perhaps, in closing, it deserves to bear Nina Simone’s observation, “An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times.”

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆