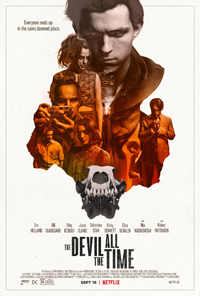

Devil May Care: Campos Composes Heady Southern Gothic

For his fourth feature film The Devil All the Time, based on the 2011 novel by Donald Ray Pollock (who is on hand as a guiding omniscient narrator), director Antonio Campos aims for something more ambitious with a sprawling Southern Gothic saga, intersecting three distinct storylines spanning eight years infected by turbulent events. Southern Ohio and West Virginia become the backwoods foreground for a tale of violence, trauma, and virulent corruption from both the law and the pulpit with a dizzying set of connected characters.

For his fourth feature film The Devil All the Time, based on the 2011 novel by Donald Ray Pollock (who is on hand as a guiding omniscient narrator), director Antonio Campos aims for something more ambitious with a sprawling Southern Gothic saga, intersecting three distinct storylines spanning eight years infected by turbulent events. Southern Ohio and West Virginia become the backwoods foreground for a tale of violence, trauma, and virulent corruption from both the law and the pulpit with a dizzying set of connected characters.

Its existence as a two-and-a-half-hour narrative which is cohesive, compelling and at times repulsive is a feat, though there is enough material to justify an expansive mini-series. A formidable cast, all utilized effectively, is another near-impossible achievement, almost enough to overlook how Campos skirts the narrative away from its true lurid, nihilistic potential.

In the backwoods of 1957 Knockemstiff, Ohio, WWII veteran Willard (Bill Skarsgard) decides to settle down. Plagued by memories of the war, he meets his future wife Charlotte (Haley Bennett) in the local diner, which revitalizes his zest for life (and dependence on religion), though his mother had desired for him to marry the pious town orphan/pariah Helen (Mia Wasikowska). Sandy (Riley Keough), sister of local cop Lee Bodecker (Sebastian Stan), gunning to be elected as the town Sheriff, works alongside the kindly Charlotte. Sandy also meets her future husband Carl Henderson (Jason Clarke) in the same fashion. Life is initially tranquil. Willard and Charlotte have their son Arvin and buy a home, while Helen marries local revivalist preacher Roy Laferty (Harry Melling), giving birth to daughter Lenora. But cancer creeps into Charlotte’s body, and when a tragedy also befalls Helen, these twin ripple effects echo through time, poisoning the future. In 1965, when orphans Arvin (Tom Holland) and Lenora (Eliza Scanlan) have grown up together under his grandmother’s roof, the violence shrouding their lives returns when the Reverend Preston Teagardin (Robert Pattinson), a handsome charlatan, comes to town.

The Devil All the Time plays like Bret Easton Ellis attempting to navigate William Faulkner, a coterie of grotesque humans converging across a brief yawn of dysfunctional intergenerational conflicts doomed for a crash course. A broad overview might suggest it’s a study of how America grew into a continually warped perversion of corrupt systems hiding behind the eternal façade of religion, the fractured humans lurking behind it the result of historical trauma inflicted upon the lost generation, whose men returned from WWII anguished and vulnerable without proper care or beneficial outlets to heal themselves. The inheritance of a Luger, a German pistol brought back from the war, which fired a fateful bullet in a mercy killing, returns to exact vengeance and retribution, sealing the fate of our protagonist and simultaneously ending a murderous rampage. Rather than a McGuffin, it’s a metaphor for what’s actually passed down between generations of white America.

Tom Holland is a standout as the sympathetic Arvin, navigating the difficult balance of lost innocence whisked towards a devious fate which lends the narrative an air of a Southern Fried Greek tragedy. Shot by Lol Crowley (Dau; Vox Lux; 45 Years), the look of the film juxtaposes the changing landscapes of the late 1950s vs. the mid 1960s, although there’s a lack of sweltering, sweaty tawdriness suggested by such proceedings. One wishes for a bit of some good ole’ Tennessee Williams hysteria in the dialogue, as only Robert Pattinson’s diabolical Rev. Teagardin broaches such energies (his sputtering of “Delusions!” from his pulpit is a definite highlight), an odd-casting choice not unlike Marlon Brando in the lead of 1960’s The Fugitive Kind.

Casting remains a strange curiosity of the film, with nearly all principal cast members being either British or Australian, all (somewhat) avoiding any obvious distractions to this fact. The 1957 opening lays the groundwork for the eventual intersections, presenting a strange world of the dangerousness of religion on uneducated minds and its ability to create supreme mania.

The chilly segue into the warped world of the Henderson’s gives Riley Keough one of her best roles in a continual string of macabre material (like the recent The Lodge or her grisly demise in The House That Jack Built), but one wishes a more extensive running time would have allowed for some more characterization of this troubling couple, such as their motivations and segue into normalized madness. What happens to them and the legacy of their crimes becomes nearly muted when stacked against the superior character work of the multitudinous competing tangents.

By the time we get to Holland and Eliza Scanlan as the grown orphans set to inherit nothing but the wind, Campos segues into a sort of fantastic sequel to something like The Night of the Hunter (1955). Strange, violent and justifiably messy considering the murky environment in which the narrative is trapped, The Devil All the Time is an impressive segue from the maudlin (meant as a compliment), intimate parameters defining early works like Afterschool (2008), the vibrant Simon Killer (2012) and the sublimely potent 2016 film Christine (read review).

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆