Peach Be With You: Simon Harvests Bitter Reality in Solid, Steady Family Drama

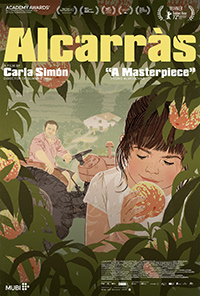

Returning to the rural experiences which defined her 2017 debut Summer of 93, Carla Simón expands her scope with the ensemble drama Alcarràs, set in a small village in Catalonia. Balancing intergenerational conflicts as an impending transition looms for one large family facing eviction from land they’ve farmed for decades, with more universal themes regarding corporate takeover and the continual diminishment of the working class, it’s a surprisingly smooth, cohesive narrative considering characters and themes. At the same time, there’s an inescapable familiarity to Simón’s film tempering an otherwise impressive achievement in tone and pacing. Eschewing excessive dramatic catalysts, it’s a film which itself feels like the seasons determining life in the countryside, an inevitable progression to change, death and potential rebirth.

Returning to the rural experiences which defined her 2017 debut Summer of 93, Carla Simón expands her scope with the ensemble drama Alcarràs, set in a small village in Catalonia. Balancing intergenerational conflicts as an impending transition looms for one large family facing eviction from land they’ve farmed for decades, with more universal themes regarding corporate takeover and the continual diminishment of the working class, it’s a surprisingly smooth, cohesive narrative considering characters and themes. At the same time, there’s an inescapable familiarity to Simón’s film tempering an otherwise impressive achievement in tone and pacing. Eschewing excessive dramatic catalysts, it’s a film which itself feels like the seasons determining life in the countryside, an inevitable progression to change, death and potential rebirth.

When the owner of their land suddenly dies, the peach farming Sole family is thrown into chaos upon receiving an eviction notice. Apparently, their father never obtained anything in writing from land owner Senior Pinyol, who purportedly gave it to him. Pinyol’s son now desires to tear down the peach trees and install solar panels, turning the village of Alcarras into a solar empire. Qumet (Jordi Pujol Dolcet) refuses to acknowledge this reality, angrily turning down Pinyol’s offer to let his family stay and install solar panels. As this will likely be their last harvest and at least mindful of dwindling resources, Qumet’s wife and children assist in gathering the peaches, while his two sisters are forced to make other choices for the future, causing sudden, intense rifts in the family. Add to this dilemma a local strike amongst the local farmers, angry about the prices they’re being paid for their crops. Reluctant to join the protests due to his own significant issues, Qumet’s eventual participation highlights an even more troubling elimination on a broader scope. With the season coming to a close, the Sole family at last force themselves to gaze into an unknown future.

Simón does a fine job of dropping us directly into the Sole family’s dilemma and then letting everything unspool quite naturally. Family relationships, as in which child belongs to which parent and each of the various characters’ tics and trajectories feels gracefully organic and, perhaps most impressively of all, easy to differentiate. Compared to something in recent memory balancing extended familial bonds, like Paolo Sorrentino’s coming-of-age drama The Hand of God (2021), which desires to be kooky rather than human, Simón’s accomplishment feels effortless.

Considering the bubbling ease of the children, oblivious to the muted anguish of their parents, suggests much of the family dynamic was improvised. As the children bustle about as if they’re in an eternally endless summer, Simon branches out and juxtaposes the realities of the layered family, from the older teens struggling to pursue their own interests while trusting their parents know what’s best, to the the trio of Sole adults, lorded over by the dominant Qumet, throwing himself into literally backbreaking fury.

There is a sense in Alcarràs of ‘the old ways,’ wherein the landowners simply made a verbal contract, allowing for the Sole clan to be evicted by the new generation in control, and the more insidious, manipulative ‘new ways’ of capital hierarchy. The Sole family and their peach farm are suddenly obsolete, part of a dying tradition for which there is little support. As their aging patriarch blindly clings to the possibility they will find proof of their ownership and Qumet expresses wrath but makes no attempt to plan for what’s next, the family is torn asunder by his sisters, forced to make their own destiny. Left in the lurch is Qumet’s wife Dolors, with Anna Otin delivering the standout performance as a sweet mother whose input largely gets ignored. Simon develops a startling hierarchy about the land ownership through a repeated motif regarding the extermination of rabbits, who compromise the crops. Their obliteration is much like the reality of the family, driven from the land they inhabit and depend upon, channeling ideas about who or what actually ‘owns’ the land, or earth, being used.

Beautifully shot by Daniela Cajias, Alcarràs eventually lands where it intended all along, and one can’t help but think of the chopping down of the cherry trees in Chekov’s The Cherry Orchard when the machinery comes to raze the land. It’s abrupt and alarming, even as it was expected to happen all along, and one gets the sense Qumet and his extended family aren’t exactly prepared for what’s next. Unlike Chekov, who was writing about the remnants of a fallen oligarchy, there’s a sense of trenchant exploitation in store for what’s next, or what’s possible. In a sense, there’s hope, but Alcarràs also exudes exhaustion by the time we get to the end credits, which is, perhaps, the film’s most subtle and meaningful virtue.

Reviewed on February 17th at the 2022 Berlin International Film Festival – Competition Section. 120 mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆