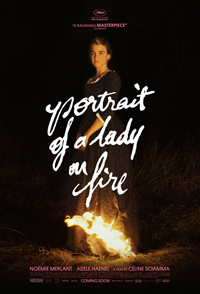

Paint it Bright: Sciamma Dazzles with Career-Best, Ardent Period Drama

You only need a few seconds to fall in line with Céline Sciamma’s commanding directorial effort, as the main character seizes the frame directing the eye of a group of students and the audience as a whole. The French filmmaker behind Tomboy and Girlhood is back and aiming higher than ever, with an 18th-century story of attraction between two women, a painter and a Countess’ daughter, set on the windy coast of Brittany. Masterful in her handling of historical restraint and simmering desire, Sciamma strips away all distractions and leaves only the essential onscreen, embodied by emphatic performances from Noémie Merlant and Adèle Haenel. Such clarity makes it easy for the film’s themes to support each other seamlessly, with the artistic process and the act of looking serving as a metaphor for forbidden love and vice-versa.

You only need a few seconds to fall in line with Céline Sciamma’s commanding directorial effort, as the main character seizes the frame directing the eye of a group of students and the audience as a whole. The French filmmaker behind Tomboy and Girlhood is back and aiming higher than ever, with an 18th-century story of attraction between two women, a painter and a Countess’ daughter, set on the windy coast of Brittany. Masterful in her handling of historical restraint and simmering desire, Sciamma strips away all distractions and leaves only the essential onscreen, embodied by emphatic performances from Noémie Merlant and Adèle Haenel. Such clarity makes it easy for the film’s themes to support each other seamlessly, with the artistic process and the act of looking serving as a metaphor for forbidden love and vice-versa.

When Marianne – defined by her professional ethic as a painter and teacher, and ready to jump into the water for the sake of her canvases – shows up at the mansion of a French countess, it is with a distinct air of mystery and foreboding. Hired to deliver a portrait of the countess’ daughter, which a Milanese suitor will then use to evaluate whether to marry the girl or not, she’s repeatedly warned of the difficulty of the task ahead. The house is cold, empty, and Héloïse haunts it. At first Marianne can’t even get a glimpse of her, let alone sit her down to capture her gaze. It’s an Hitchcockian prologue, flirting with echoes of the supernatural in its fixation on the exorcizing power of the painted image. Valeria Golino, as Héloïse’s mother, knows the stakes better than anyone as she recounts the feeling of entering a room and finding her own effigy already there, as if it were waiting for her.

Hiding her true mission, Marianne initially poses as a companion to Héloïse. The Countess’ daughter is privileged enough to be able to push social norms to their breaking point, but is also imprisoned by them. Marianne is more mindful of the rules of the game, and yet she transcends them somehow with her cutting-edge independence. The romantic dance between them is traced to perfection in a series of encounters that zoom in on their respective isolation, only for Sciamma to complicate their symmetry with the introduction of the maid Sophie. Instead of breaking the spell, it deepens their bond and makes for a better exploration of womanhood in the historical context of the limitations placed on their bodies, their lives, and their work.

And then there’s the painting itself, which keeps getting defaced, burned, re-conceived throughout as their relationship develops. Sciamma’s biggest achievement might not even be the way it builds a love story around its symbolic value, but rather the opposite, using the two women’s attraction as fuel to craft an allegory of professional determination finding its way through hardship. It truly works both ways, like an hyper-sensual palindrome that leads back to Haenel or Merlant’s faces whichever way you choose to read it from. And in a film so concerned with keeping their hands down, locked in a pose since the first shot, the faces do all the work, to marvelous effect. Portrait of a Lady on Fire is Sciamma’s best film to date, achieving the full form her previous work could only suggest.

Reviewed on July 25th at the 2019 New Horizons International Film Festival – Opening Film. 119 Minutes.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆