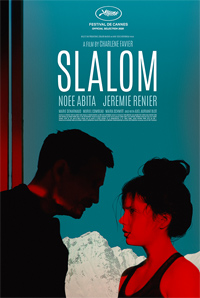

Slippery Slopes: Favier Blends Coming-of-Age and Sexual Assault Narrative in Chilly Debut

There’s an immediate discomfort apparent in the opening act of Charlène Favier’s debut Slalom, a title which proves to be a stellar metaphor for the sexual awakening of its teenaged protagonist indicating the graceful navigation of obstacles and barriers as she winds through twists and turns on the trail.

There’s an immediate discomfort apparent in the opening act of Charlène Favier’s debut Slalom, a title which proves to be a stellar metaphor for the sexual awakening of its teenaged protagonist indicating the graceful navigation of obstacles and barriers as she winds through twists and turns on the trail.

Once we’re introduced to the main players settling into their isolated confines, which includes a handsome, tenacious ex-athlete turned ski-instructor and his comely, emotionally neglected protégé, the stage is set for a sprint into sexual assault. While Favier avoids skiing down all the predictable slopes and maintains a narrative poise, which surprises considering the subject matter, these are indeed chilly scenes of a winter oft repeated and normalized across every culture and climate.

Lyz (Noée Abita), a fifteen-year-old student with a passion for skiing, finds herself accepted in an esteemed ski club in the French Alps. Despite being a novice, she shows surprising skill, and will be groomed alongside her peers by the passionate Fred (Jérémie Renier), once a renowned athlete who has turned into a coach with a certain reputation. Since her mother (Muriel Combeau) has accepted a new job (and love interest) in Marseilles, Lyz is left to her own devices and soon finds herself gravitating to the charms of Fred, whose attentions assist in honing her commitment and performance to the craft. When certain boundaries are crossed, Lyz finds herself even more mired in secretive isolation, which begins to take an emotional toll.

Narratives predicated on skiing either lean towards lighthearted, such as 2015’s Eddie the Eagle (which concerns ski jumping), and/or, like most sports related films, focus on male perspectives and protagonists, the most notable being Michael Ritchie’s classic Robert Redford drama Downhill Racer (1969). Newcomer Noée Abita, who is given a more typical trajectory than in her debut, Lea Mysius’ Ava (2017), reflects a serene, but deep reservoir of conflicting feelings in her gaze. Wide-eyed and impressionable, we learn little of her time prior to acceptance into ski club other than she’s somewhat of a novice faced with a detached relationship to one of those mothers (Muriel Combeau, supporting player in Leconte’s 2001 film Felix and Lola) intent on starting her own ‘chapter two’ sans the baggage tying her to a past life.

Poignant intimacies and taboo desire have marked many of Belgian Jérémie Renier’s roles, who started out as a Dardenne discovery and then quickly became an arthouse conduit for Ozon (the 1999 queer retelling of Hansel & Gretel in Criminal Lovers) and frequently dips his toe into memorable discomforts, including alongside his own brother Yannick Renier in Private Property (2006) and even last year as a man fixated on his step-sister in Frankie (2019).

As the careless and egotistical Fred, a man too sexy for his shirt, Renier isn’t so much playing an in depth characterization but a typical man so empowered by the control his position and looks afford him he’s become desensitized to what he’s risking (his continual admonitions of Lyz when she responds with any affect to just “respire/breath” eventually begin to grate as a form of subtle gaslighting). His invitation to allow Lyz into his home with his partner is one of the more egregious examples of this—more so the inability for any of the adults to address the increasingly fat elephant in the room.

Favier’s script, co-written by Marie Talon, is obsessed with the notion of sacrifice, the students foregoing normalcy to become champions for France, while Fred’s sacrifices have led him to feel justified in seduction of children as compensation for a career cut short. Favier isn’t asking us to be comfortable or titillated, not is she condoning the sexual assault in Slalom, although it’s impossible to gauge the potential detriment this may have on Lyz as she grows into womanhood. But Favier is showcasing the murky stain infused in the emotional and sexual development of this fifteen-year-old, who begins her journey unable to vocalize why she wants to be a top ski champion. “I just want to,” she retorts when pressed. And when she reaches her goals, it’s her epiphany of how and what she’s feeling in response to achieving them which paints her narrative arc, an internalized struggle Favier manages to communicate visually and throughout the film’s subtexts.

The relationship also plays out authentically, and we can feel the energy build between the slight touches and the furtive glances in locker rooms which blossom into full blown desire for Lyz when Fred sits down to explain menstruation, revealing a powerfully restorative interpretation of a menstrual cycle, describing it as a woman’s body following of the pull of the moon. “It’s cosmic.” Too bad all the smooth talk revealed itself to be some sly grooming, but nevertheless, it succinctly clinches the sincere dynamic of Favier’s characters realistically and effectively.

Reviewed on June 26th – Cannes 2020 Label – THE FIRST FEATURES Section. 92 Mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆