The Equality in Dying: Sollett’s Topical Gay Rights Issue Explores Yesterday’s Nightmares

Had a film like Freeheld been released in the late 2000s, shortly after the trailblazing gay rights victory documented here transpired, it would have seemed courageous and daring even despite its significant flaws as a social issue film about gays made specifically to appeal to heterosexual sensibilities. In recent years, following the increased progress in gay rights, from the repeal of Proposition Eight in 2013 and this year’s US Supreme Court decision allowing same-sex marriage nationwide, we’ve seen several major prestige pictures nabbing lucrative awards, like 2013’s extremely spruced up The Dallas Buyers Club. As far as the importance of awareness and acceptance goes, these films are still important, now that some distance from the period allows the chance for significant introspection on the ragged road to basic vestiges of equality. The 2005 story of Laurel Hester and her partner Stacie Andree as documented here manages to outline basic bullet points, and was written for the screen by Roy Nyswaner, who famously penned another landmark social issue film, 1993’s Philadelphia. The combination of great acting talents and incredible topicality of the project will most likely attract a considerable appreciation—and yet, the film’s rigidly square sensibilities rob it of an aching potential to explore the socially accepted homophobia we’re only years removed from.

Had a film like Freeheld been released in the late 2000s, shortly after the trailblazing gay rights victory documented here transpired, it would have seemed courageous and daring even despite its significant flaws as a social issue film about gays made specifically to appeal to heterosexual sensibilities. In recent years, following the increased progress in gay rights, from the repeal of Proposition Eight in 2013 and this year’s US Supreme Court decision allowing same-sex marriage nationwide, we’ve seen several major prestige pictures nabbing lucrative awards, like 2013’s extremely spruced up The Dallas Buyers Club. As far as the importance of awareness and acceptance goes, these films are still important, now that some distance from the period allows the chance for significant introspection on the ragged road to basic vestiges of equality. The 2005 story of Laurel Hester and her partner Stacie Andree as documented here manages to outline basic bullet points, and was written for the screen by Roy Nyswaner, who famously penned another landmark social issue film, 1993’s Philadelphia. The combination of great acting talents and incredible topicality of the project will most likely attract a considerable appreciation—and yet, the film’s rigidly square sensibilities rob it of an aching potential to explore the socially accepted homophobia we’re only years removed from.

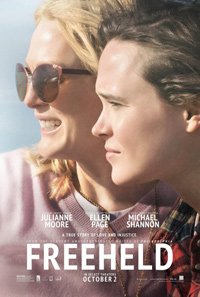

Laurel Hester (Moore) is a decorated New Jersey police detective, diagnosed with cancer soon after moving into a new home with her domestic partner, Stacie Andree (Ellen Page). Recent laws passed in the state afforded benefits to domestic partners, but Laurel is a county employee, and thus subjected to a decree stating the county officials, Freeholders, have the option to exercise this as an option. Laurel’s request to leave her pension to Stacie is denied, arousing a firestorm thanks to Laurel’s work partner Dane Wells (Michael Shannon) and the eventual interest of activist Steven Goldstein (Steve Carell). Eventually, the public outrage over the Freeholders’ continual denial of Laurel’s request reaches national attention.

Julianne Moore, still fresh off a stellar 2014 which saw her take home a Best Actress prize at Cannes for Maps to the Stars and an Academy Award for Still Alice, gives another multi-faceted performance as an ailing woman (Moore seems to excel at these, from Safe onward) here, and she’s quite affecting as Laurel Hester. However, Sollett, whose last feature was 2008’s ungainly Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist, attempts to accomplish too much in too little time.

Unsuccessful in portraying a believable relationship between Moore and Page, who aren’t given ample opportunity at even attempting chemistry, is mixed uneasily with Nyswaner’s pointed dialogue—as in the portrayal of obtaining a domestic partnership is depicted. Perhaps if the film wasn’t a mixture of social issue and relationship drama Sollett could have leaned more easily into one or the other aspect and this may have seemed less cookie cutter.

Though Page is unfortunately rather flat, especially in comparison to Moore, Michael Shannon manages to share some of the film’s best sequences. The exploration of Moore and Shannon’s partnership is related more subtlety, depending on visual cues (until, to help us out, someone has to blurt it out just in case we missed it) to relate Shannon’s attraction for his partner (it’s reminiscent of how Nyswaner managed a more emotionally potent chemistry between the Tom Hanks and Denzel Washington characters in Philadelphia, whereas boyfriend Antonio Banderas felt peripheral).

Worst of all is Freeheld’s bid for broad comic relief in the form of the flamboyant activist gratingly portrayed by Steve Carell. To be fair, this wouldn’t have been a fashionable role for any actor to portray since it depends solely on stereotypes and the type of queer characteristics progressive straight people tend to be amused by easily.

Regardless of the faults in Freeheld, it does relate an important instance on the journey to marriage equality, recalling the reluctance of many to jump onto a bandwagon divided by terminological differences between definitions of ‘marriage’ and ‘equality.’ Though at times reminiscent of a production you’d easily see produced for television, Freeheld is presented with great compassion, and the success of films like these should hopefully open the door to more complex and varied characterizations of queer characters down the road.

Reviewed on September 14th at the 2015 Toronto International Film Festival – Galas Program. 103 Mins.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆