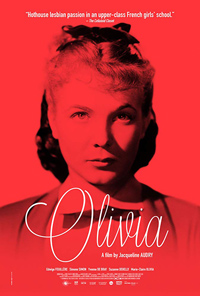

Teacher Pets: Audry’s Lesbian Melodrama Reclaims the Spotlight in New Restoration

Returning to dispel the historical erasure of queer representation in cinema is Olivia, a restoration of Jacqueline Audry’s 1951 melodrama, adapted from the only novel by Dorothy Bussy, an English teacher and translator responsible for translating all of Andre Gide’s works into English thanks to their decades spanning friendship. Besides a reclamation of early lesbian representation (this was a full decade before openly acknowledged lesbian representation would arrive in US cinemas with 1961’s tragedy, The Children’s Hour, which also deals with teachers), the restoration is a reminder of the importance of Audry, who worked steadily as a director from 1946 to 1967, often adapting notable novels (including works by Jean-Paul Sartre and Colette) and is perhaps best remembered for first tackling Gigi (1949), which Vincente Minnelli would later churn into an Academy Award winning musical in 1958. Falling into oblivion during the birth of the Nouvelle Vague, Audry’s filmography is ripe for recuperation considering her masterful talent for mounting lavish period productions, and retaining the queer elements from source material considerably toned down for this film version.

Returning to dispel the historical erasure of queer representation in cinema is Olivia, a restoration of Jacqueline Audry’s 1951 melodrama, adapted from the only novel by Dorothy Bussy, an English teacher and translator responsible for translating all of Andre Gide’s works into English thanks to their decades spanning friendship. Besides a reclamation of early lesbian representation (this was a full decade before openly acknowledged lesbian representation would arrive in US cinemas with 1961’s tragedy, The Children’s Hour, which also deals with teachers), the restoration is a reminder of the importance of Audry, who worked steadily as a director from 1946 to 1967, often adapting notable novels (including works by Jean-Paul Sartre and Colette) and is perhaps best remembered for first tackling Gigi (1949), which Vincente Minnelli would later churn into an Academy Award winning musical in 1958. Falling into oblivion during the birth of the Nouvelle Vague, Audry’s filmography is ripe for recuperation considering her masterful talent for mounting lavish period productions, and retaining the queer elements from source material considerably toned down for this film version.

Without a doubt, Olivia is the product of the influence of Madchen in Uniform, the 1931 German classic about a schoolgirl who falls in love with her headmistress (later remade in 1958 starring Romy Schneider). Strangely enough, Audry’s Olivia was released the same year as Mexican director Alfredo B. Crevenna tackled a Madchen adaptation with Muchachas de Uniforme, a film which captures a similarly overt depiction of tempestuous, hothouse desire in a girls’ boarding school.

We meet the titular Olivia in a carriage ride to school, an outsider marked by her foreign name, which she’s told “means nothing.” Immediately, Olivia finds herself drawn to the magnetic persona of Miss Julie, played with delirious aplomb by Edwige Feuillere, lending a copy of Sophie’s Misfortunes to Oliva from her library because, as the other students tell the new ward, their teacher believes “reading his healthy” (of note, Audry’s 1946 debut was a scandalous adaptation of Sophie). Audry takes pains to formulate relationships between the support staff at school, such as the ornery cook (Yvonne de Bray) and the deprecating mathematics teacher (Suzanne Dehelly) in a tradition not unlike the “support staff” of The Diary of a Chambermaid, Octave Mirabeau’s novel thrice adapted for the screen. However, the trap soon becomes a familiar one, a scenario as often used to introduce lesbianism through vampirism or witchcraft.

As Olivia falls under the spell of Miss Julie, we learn she seems to have been used as a plaything for the ailing Miss Clara (Simone Simon of Cat People, here surprisingly and perniciously petty, a far cry from her woebegone English language roles, including Robert Wise’s fun but little seen Mademoiselle Fifi, a 1944 Guy de Maupassant adaptation), whose constant migraines and refusal to eat are a reaction to being abandoned by Miss Julie. The reappearance of another star student, Laura (Elly Claus), also triggers Miss Clara’s emotional downpour—as both young women gravitated towards Julie instead of herself. So, like an emotional vampire without anyone to feed off of, her health begins to dwindle. Meanwhile, Miss Julie’s apparent favoritism for some of the other, prettier girls also sets this narrative apart from the usual reciprocal attachment in these scenarios (the cruelty of which marks Olivia as an opportune property for a remake starring one of France’s contemporary grand dames…one can only imagine what Isabelle Huppert, Catherine Frot or Juliette Binoche might do as the greedy intellectual Miss Julie).

Beautifully filmed by Christian Matras (of Renoir’s Grand Illusion, 1937), Olivia is an entertainingly scripted scenario of repressed lust, exemplified in every possibly way, but quite brilliantly through a script filled with observational bon mots (Audry’s own sister Colette adapted the text, with dialogue from her husband, Pierre Laroche, who had scripted Marcel Carne’s Les Visiteurs du Soir, 1944). Through the many literary passages uttered by Feuillere (who scored a BAFTA nomination for her work here), it is perhaps the passage, borrowed from the Book of Job, “I have made my bed in the darkness” which haunts the final frame, as Olivia clatters off in another carriage with the cook and Miss Julie escapes to Canada to wend her magic on another unsuspecting legion of young women.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆